-

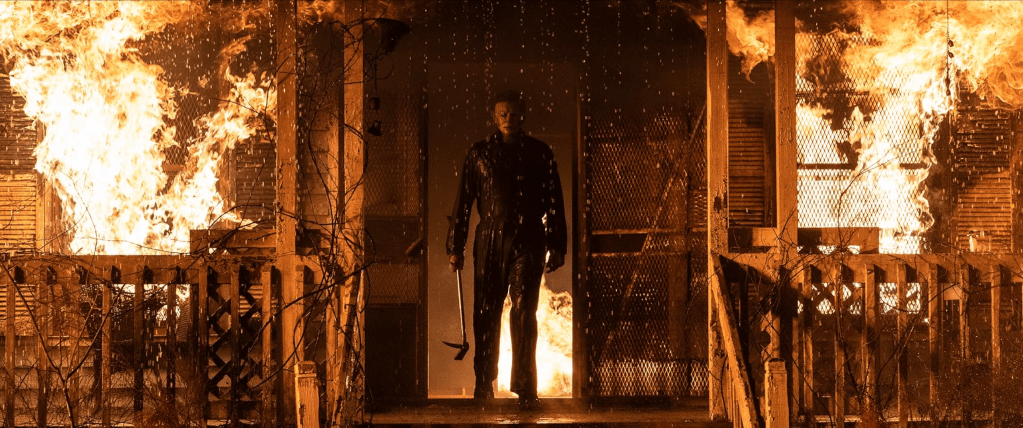

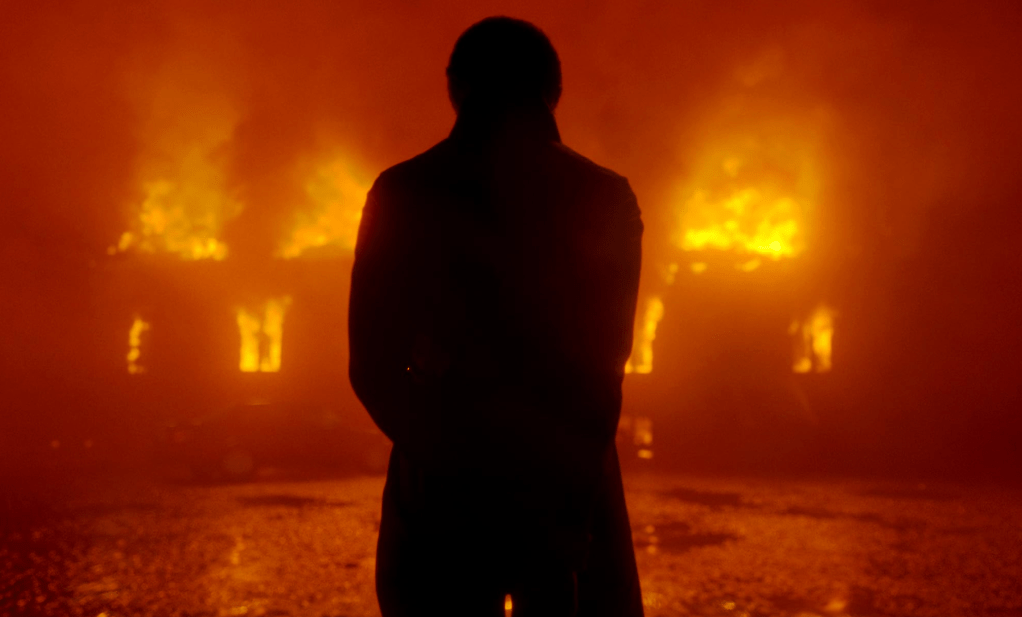

Halloween Kills .. or it kills my brain.

What it is about?

Oh what a miracle, Michael Myers survived. Now he is mighty pissed and runs amok.

What is it really about?

“The evil dies tonight”, it says, in the night of Halloween 2018, directly following the events of the 2018 film, proclaimed by the beer-moist after-work lips of the Haddonfielder village Vollhonks, who are slowly but surely foxy because of the Michi, because – now times fat-poor butter by the fish – this can not go on, these murders and so. That’s mean, evil, what Michi is doing, it has to end. Now, right here, go! Before the blood dries everywhere. No street sweeper, no matter how hard he works, will be able to clean up that much blood. So get Michi on it, we’ll make short work of it.

“Evil dies tonight”, it says again, while the Haddonfield rage citizens will pull out the pitchforks and light torches and as a small mob tingles through the Halloween night streets. Fittingly, the mob also includes a few survivors from 1978; so they are qualified enough to loudly rebel against this killing machine after it has to wait 40 years. And so they march extremely loaded, resentful and worried, most worried about their dear little children, and go on the disoriented search for Michi, about whose whereabouts they have no clue and apart from that they have so no plan, how they can become at all statly to this overpowering giant, but the main thing is that the mob gets some fresh air. They always have a common enemy! The enemy, Michi, squats in the meantime in a flaming cellar, quasi symbolically the hell, and in itself it would be there also well armed for the cold winter evenings, however it becomes – spoiler!!!! – he is freed by carelessness, which is why the murdering continues again.

“Evil dies tonight”, it says again, and the Michis murders run even less slasher-typical than in the predecessor. Where usually in slashers with a nerve-racking scene set-up – in which the perpetrator lurks deeply hidden in the darkness, moving about in it like a ghost, and we watch the apparent victim being watched unsuspectingly, the grueling tension swelling immeasurably until the victim feels the threat on the back of her neck, senses the silent danger, tries to flee it helplessly and hopelessly – in Halloween Kilos we find the following scheme: hello, zack and dead. A hitherto completely unknown person is introduced, e.g. a fireman. 2 minutes later: fireman dead. More firemen. 2 minutes later: firemen dead. An old couple. 3 minutes later: couple dead. A gay couple: 5 minutes later: couple dead. Three children playing a prank on the gay couple. 5 minutes later: children dead. A couple in costume. 7 minutes later, dead. An old woman. 5 minutes later: dead. One unsatisfying, pre-game quickie after another. And that’s just the first half of the film.

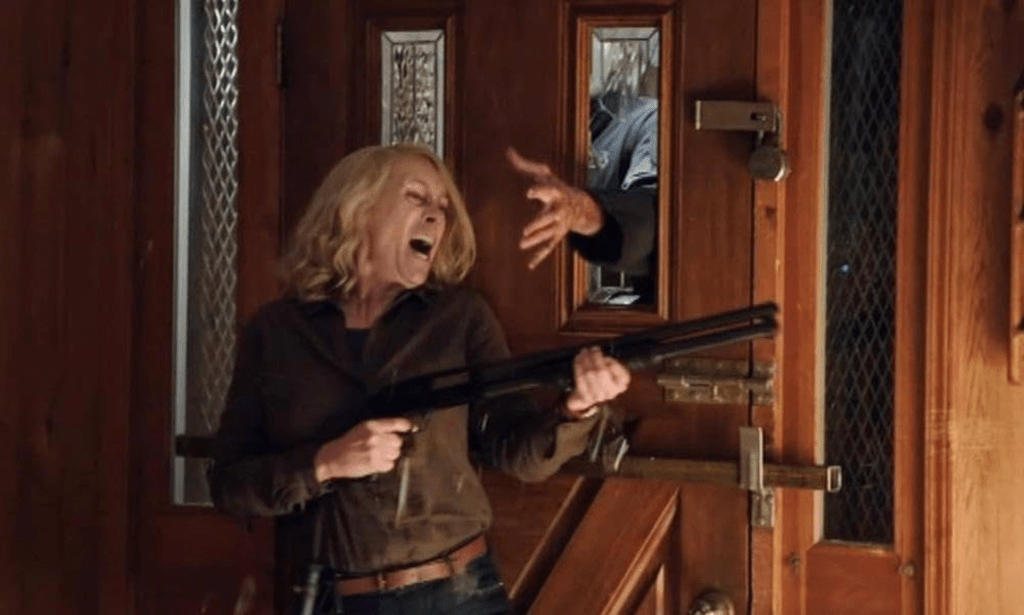

“Evil dies tonight,” it says again and again, and at some point I don’t even itch anymore; the murders, the victims, the kills, the mob trumpeting their eternally same slogan. I’m completely numb, just like Michi’s knife, which he rams into the body of one after the other. They don’t even bother to introduce closeable characters anymore, who offer a projection surface for their own fears, so that I can shiver with horror, and at worst even pee my pants. Even the main characters from the first part, namely Laurie Strode, daughter Karen Strode and granddaughter Allyson Strode, degenerate here into complete sideshow characters who fritter away 80% of the film in the hospital, where the Michi never sets foot. Instead, the story is devoted to the mob, which actually makes it to Laurie & Family’s hospital and causes quite a stir there.

“Evil dies tonight,” it is said again and again by the annoying mob, ever larger and louder. Brain amputees gargling the same baloney over and over again, showing off their beer-drunk muscles. Small-town Nazis who demand total annihilation and in their blind rage soon harass an innocent until he takes flight, only he can’t fly and therefore claps his hands on the ground (whereupon no one claps their hands, only I put my hand to my forehead). Deliberately parallels are made here to real citizen protests. In particular, when the mob storms Haddonfield Hospital, it is strikingly similar to the storming of the Capitol, a disaster that serves as a culmination and simultaneous swan song of a pathetic presidency of the – Hands up! – Absolutely Greatest President of the Absolutely Greatest Country in the World Mr. Lovely Donald Trump has cast a large, heavy shadow over civic political movements in the United States. That the mob in Halloween Kills is equated by its bold presentation with the gobshites at the Capitol and thus virtually translates any form of political citizen protest as a vandalistic, destructive, mindless movement that risks human life leaves a bitter aftertaste in my mouth.

“Evil dies tonight,” it says again and again, and I think hard about who is actually meant by “evil.” Is it really Michi? A stocktaking after the end of the film shows for me: Died “tonight” are above all the Haddonfielders, who jump over Michi’s blade in rows. Michi, on the other hand, was not even batted an eyelash. So is the population of Haddonfield actually meant by this pathetically unimaginative slogan as “the evil” that “dies tonight”. And in principle, let’s face it, of course the Haddonfielders have to die, because otherwise we wouldn’t be watching the movie at all. The hero in this story is Michael Myers, because he is – with the exception of part 3 – the only constant in all Halloween movies. It’s only because of him that we watch Halloween at all, not because of Laurie Strode or the dumb bunch of monkeys that roam the empty streets as self-appointed vigilantes. Michi is depicted on the posters. There are Halloween costumes, merchandise, etc. from him. We don’t want anyone from the Strode clan, Dr. Loony Loomis, the mob or anyone else to get Michael Myers, we want them to get a good beating from Michael Myers. Once Myers is dead, the movie ends for us, the franchise ends for us. Only with him can the franchise continue. Whoever wants to take that away from us has to be the true evil, and that is now the Haddonfield population, who want to stop him and destroy him once and for all. True story, I’m sorry. And also – doesn’t matter, but I’ll bring it up anyway – doesn’t the name Michael also mean “Who’s like God?” you godless Myers rabble-rousers!??

“Evil dies tonight”, it is said again and again, and actually it means: “Your brain dies tonight”. Please don’t get broody, the gray cells are supposed to die, to be put in the ground, there is also a funeral feast of nachos with cheese sauce and Coca Cola in a 1 liter cup for 12,99€. It’s a movie and this movie is garbage. A movie without a beginning, without an end and most importantly: without a middle.

“Evil dies tonight”, it says again and again, while the film tries to whitewash its absolute lack of content and atmosphere with hefty violence and a bevy of references. Have you seen. The three kids who prank the gay couple are wearing the same Silver Shamrock Novelties masks as the kids in Halloween III, and did you get the meta joke that in Halloween Kill, the sequel to Halloween 2018, Laurie grunts as much in bed as she did in Halloween 2, the sequel to Halloween 1978? If not, watch one of the many-cell “25 Things You Missed In Halloween Kills” and freeze at how smart as makers they are!

“Evil dies tonight,” they say again and again; only, alas, the bad never dies, and that’s why it gives us this movie. It laughs at us that we even spend money on such a low-quality product. It’s like a vacuum cleaner, where you have to suck through the pipe yourself and besides, it only eats the dirt. No effort was made with the script, not with the cinematographic staging (compared to the first one, which is at least atmospheric), not with the acting.

Conclusion

So dumb, it killed half of my brain cells.

Facts

Original Title

Length

Director

Cast

Halloween Kills

105 Min

David Gordon Green

Jamie Lee Curtis as Laurie Strode

Judy Greer as Karen

Andi Matichak as Allyson

James Jude Courtney as The Shape

Nick Castle as The Shape

Airon Armstrong as The Shape (1978)

Will Patton as Officer Hawkins

Thomas Mann as Young Hawkins

Jim Cummings as Pete McCabe

Dylan Arnold as Cameron Elam

Robert Longstreet as Lonnie Elam

Anthony Michael Hall as Tommy Doyle

Charles Cyphers as Leigh Brackett

Scott MacArthur as Big John

Michael McDonald as Little John

What is Stranger’s Gaze?

The Stranger’s Gaze is a literary fever dream that is sensualized through various media — primarily cinema, which I hold in high esteem. Based on the distinctions between male and female gaze, the focus is shifted through a crack in a destroyed lens, in the hope of obtaining an unaccustomed, a strange gaze.

-

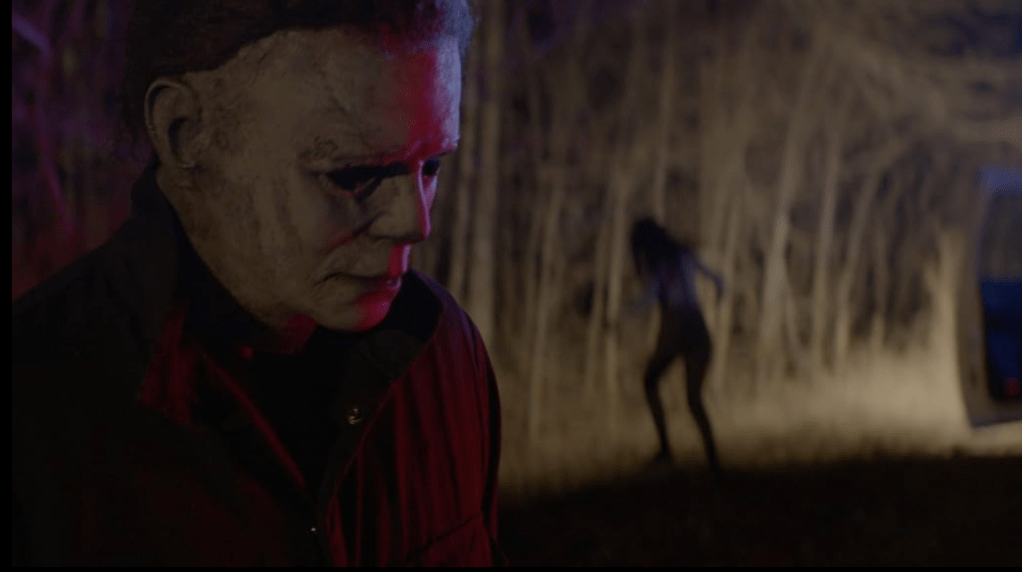

Halloween (2008) … or Repeating the same thing again.

What it is about?

It’s Halloween. Once again. Michael Myers is back. Once again. But this time it’s different. Or not.

What is it really about?

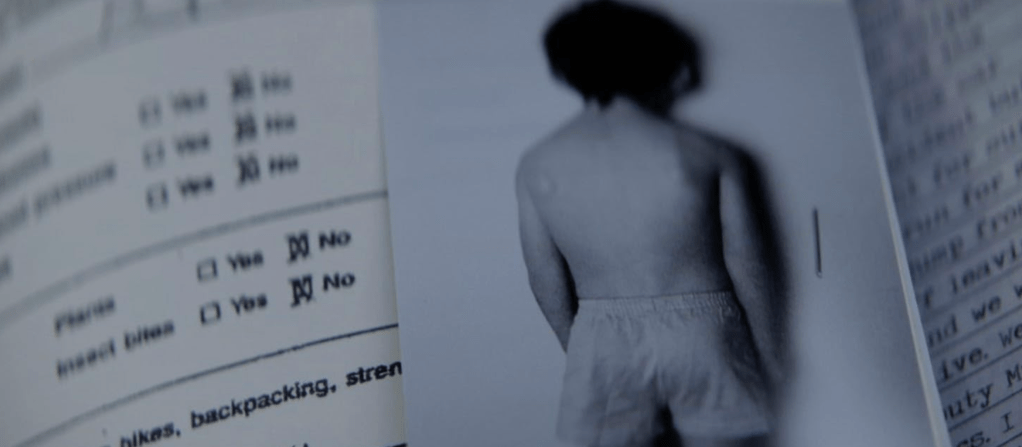

Mikey-boy is back! Finally! For 40 years he has been searching the woodchip wallpaper in an insane asylum for funny figurines, after he – not quite so gloriously – sent three people to the afterlife in 1978. It can happen. Not his best day, admittedly, but as his psychiatrist Dr. Loomis says, Mikey-boy is a bad boy and bad boys do bad things. Prove me wrong.

Anyway, he is back now. The crowd cheers, the knives are sharpened and at worst the popcorn gets stuck in your throat in shock before Mikey-boy plunges the knife into your neck. Actually, he had a cozy Halloween ahead of him in 2018, the classic trick-or-treat bash, but it didn’t turn out that way, because one day before the ghost test, two podcasters swooped in and had to get him all fuzzy. They held up to him the dearly beloved William Shatner mask that he used to go on murder sprees with so beautifully. But while he didn’t wrinkle his nose once, his moronic fellow inmates kicked and hooted and yelped and mewed in the most crazy way. What a commotion it was, how annoying and unnecessary. Like something out of a bad movie, a bad, unimaginative script crammed onto the screen, showing the most clichéd portrayal of mentally ill people. Bad, so the viewer – before he leaves the cinema now – is quickly reconciled by the Halloween writing being faded in, the fiddles wailing away, and the frantic synth patter buxing the pulse with joy and with fear to immeasurable levels. The opening credits are the first small highlight for me.

Then they try to tell something like a story. Something about the True Crime podcasters, who I couldn’t care less about; something about Laurie Strode, who escaped from Mikey-boy back in 1978 and is now a super tough, super armed, super paranoid bad ass bitch, in front of whom even John Rambo gets raisin nuts and who is important for the film, so that the old Mikey-boy fans ram into the cinema; then there’s something about her daughter Karen, who also only found her way into the film because she’s Laurie’s daughter and has absolutely no right to exist in this film at all; and then there’s something about her daughter Allyson, Laurie’s granddaughter, who with her teenage years appeals exactly to the target group that is also in their teenage years and has possibly never seen or heard of Mikey-boy. But that doesn’t matter for this “sequel”.

The 2018 film has little in common with the original from 1978. With the exception of the mask and that the perpetrator is called Mikey-boy and one of the hunted Laurie. In his 20s, back in 1978, Mikey-boy was a rather stoic, latently perverted fellow who stalked his victims in best voyeur manner, tracing them mousy-mouthed and eliciting a pleasurable look of discovery while stabbing his victims, quite like a childlike fascination; as if it satisfied him, the psychologically castrated one. In 2018’s Halloween, on the other hand, he’s a badass Terminator who lets nothing and no one stop him, ramming his 40 years of pent-up rage into the inferior bodies, no fascination left to elicit from them but pure murderous lust. He seems to be less a retelling of the child in the hunk’s body than more of that “absolute evil” myth that only all the films have made him into, which here in the 2018 sequel play no role at all, but so really no role at all. Allegedly. In vain. Of course, the ignored sequels also play into this film, as fan service soup, as the hinterland of the unconscious.

The richly anemic but incredibly thrilling original, which robbed the viewer of fear and terror through the sexually subversive poking and prolonged tension to the extreme, can no longer be reproduced in 2018. But it doesn’t have to. The 2018 film does not come close to the original, but can entertain with its audiovisually atmospheric staging as a slasher. Of particular positive note here are actually the teenagers, all of whom are extremely likable, even if some of them are only seen briefly. I liked just about every scene with them. To my mind, a straight slasher with only teens would have been much more intriguing, gripping as well as less picked apart and forced than with the unnecessary referent named Laurie and her daughter Karen. That the violence screw was neatly tightened and adapted to the viewing habits of the 21st century fits for me – even if I regret a little that Michael has lost his juvenile fascination for the dead as a substitute for his own chaste sexuality and virtually only kills in quickies to get to the climax quickly. In general, the subtext seems to be completely abandoned or to flourish solely in preaching “family is everything”. In the end, it’s a Disney movie with blood splatter after all.

Oh yeah, what else is there? A plot twist you can smell pretty early on, and even with exposure it stinks just as your nose predicted it would.

And lastly: What do I actually think of Halloween movies in general? I’ll put it another way: Mikey-boy could never thrill me as a slasher master the way Freddy, Jason or Chucky did. But that’s probably also because parts 4-6, H20 and Resurrection are fucking grotty cucumbers. Rob Zombie’s reinterpretation, however, I thought was successful, even if not as masterful and subtle as the original, but at least something entirely new was tried that can’t be attributed to the 2018. This relies heavily on its fan service and higher quality production.

On a side note: My theory, by the way, is that Mikey-boy only kills on Halloween because he’s a Jeck at heart, a carnival guy. He’d rather be laughing, slapping his neighbor’s thighs with laughter, than stabbing and punching, but Halloween, which is all about fright and fear, tempts him to cause fright and fear himself.

Conclusion

Boooooooooooooooring.

Facts

Original Title

Length

Director

Cast

Halloween

106 Min

David Gordon Green

Jamie Lee Curtis as Laurie Strode

Judy Greer as Karen

Andi Matichak as Allyson

James Jude Courtney as The Shape

Nick Castle as The Shape

Haluk Bilginer as Dr. Sartain

Will Patton as Officer Hawkins

What is Stranger’s Gaze?

The Stranger’s Gaze is a literary fever dream that is sensualized through various media — primarily cinema, which I hold in high esteem. Based on the distinctions between male and female gaze, the focus is shifted through a crack in a destroyed lens, in the hope of obtaining an unaccustomed, a strange gaze.

-

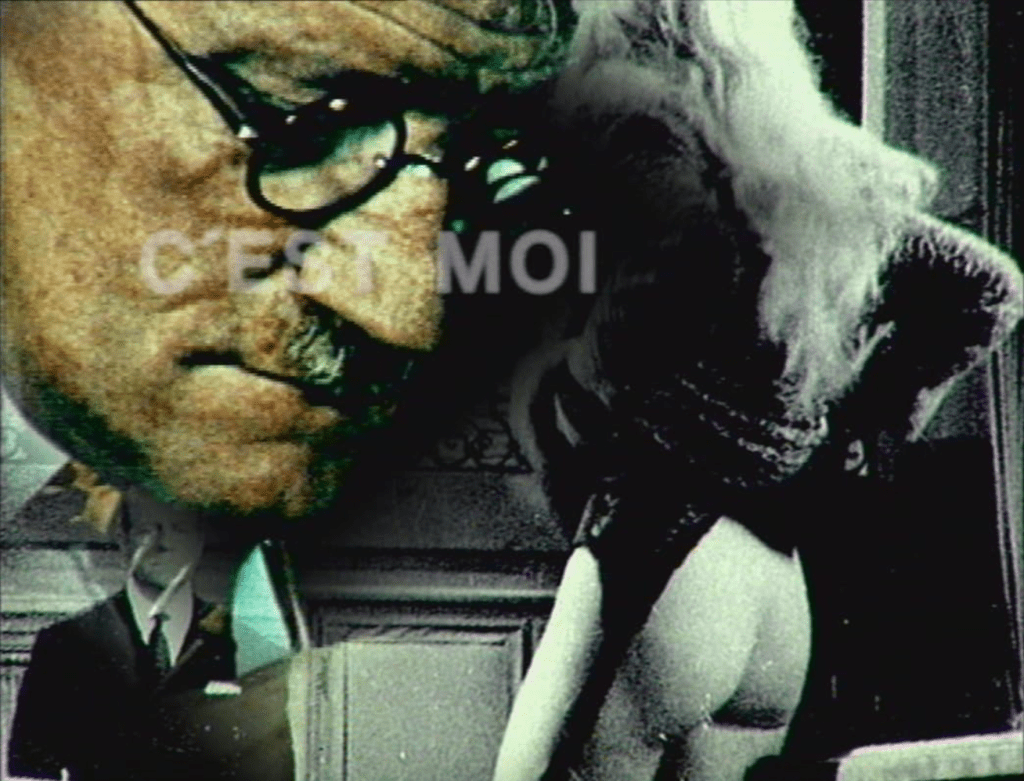

Histoire(s) du cinéma … or all about cinema.

What is it about?

Godard, who talks for over four hours about the history of cinema, about stories of cinema, about his own history with cinema.

What is it really about?

Histoire(s) du cinéma.

Histoire(s) du cinémoi.History(s) of cinema.

His story(s) of cinema.Looking at a canvas is like looking into the head of a stranger. Thought-transformed images and sounds, once sprung from the big bang of thought, which falls letter by letter into the hands of the creator and is incubated with body heat until it hatches as a word and is given birth in the clattering beat of the typewriter, that word machine which immortalizes thought and which swivels its head horizontally from left to right. In front of this mechanical apparatus a brittle voice rises, it tones, over which the typewriter clacks like a machine gun, but otherwise remains silent.

“Let each eye negotiate for itself. Do not uncover all sides of things. Keep a margin of indeterminacy.”

The fading thought that returns on paper, made immortal. And what is immortalized on paper can be revived on canvas, that projection surface which in the light bulb coaxes the thought out of the darkness, as it was equally translated from the dark, foggy thicket of the thinker’s bulb onto white paper to the world. What is revived on screen is not just entertaining flickering, it is the memory of modernity. It is a think tank and memorial about the history and stories of the 21st century. That of cinema.

About this Godards succeeds in his cinematographic essay “Histoire(s) du cinéma”. In four double episodes. Total running time: 4.5 hours. Produced for French television between 1989 and 1998. Fast forward to the then groundbreaking medium of video, which made it possible in a simple way to preserve, re-cut, recontextualize the heavy celluloid compactly in cassette form. The playground of Godard, who amassed a personal archive from whose smorgasbord he now tells the story(s) of cinema. No, this is not lexical infotainment as one would expect on Netflix. Not the multiplication tables of the film lesson, to be treated factually and eye-opening with a clipboard and freshly sharpened pencil, as once Every Frame is a Painting. Instead, Godard sits in front of the camera and behind the players to stuff the viewer again and again with sweet as well as salty popcorn until it sticks in the throat (optional: in the nose) and cheese sauce runs here and there like tears from the eyes.

Sure, Godard has since the end of the 60s anyway quite a screw loose and turns since then his own thing, of which actually no one really gets what he is shooting; the one of it annoyed, the other is fascinated by it. It’s not much different with Histoire(s), as Godard maneuvers his story(s) extremely cryptically by means of text insertions and voice-overs along a slithering red thread, condensing the presentation through the so-called story(s) with countless film excerpts, pieces of music, quotations from literature, philosophy and paintings from the visual arts. Not only does film history per se play the supporting role, but Godard interweaves his narrative into at least the following levels:

(a) The film history. Beginning in the bosom of the Lumiére brothers, with whom cinema learned to walk, via Eisenstein and Griffith, with whom it learned to speak (in film), via Hitchcock, Hawks and Ford, where it came of age, to the end of cinema, after it lost its innocence – above all through the Holocaust and its treatment of cinema (both documentary and fictionalized) – and is thrown to Mammon, reinforced by American cultural imperialism.

(b) The real human history of the 21st century, packed with (world) wars, genocides, revolutions, political and social upheavals, new discoveries, inventions. The history of a century captured (documentary) and retold (fictionalization) with the gaze of the medium of film.

(c) The fictional stories told in film. In short, the stories that are not based on true events in human history. Stories that provide escapism from reality (fantasy), muddle psychotraumatic (crime, horror), and/or psychosexual stimuli (porn).

(d) Backstories of films. About the making of a film, the shooting, the post-production, the reception.

(e) Godard’s own cinephile biographical history. From a film critic to an initially highly decorated to later for the general completely forgotten auteur filmmaker.These are the story(s) that the Histoire(s) du Cinéma, to which Godard devotes himself in this impressive and most important work: “A story that had been enumerated but never told.”

Stories that in Godard’s hands and quote ecstasy an electrifying and dreamy meme fireworks, a celestial glow, melted into those five levels of meaning, which, however, never light up separately from each other, but simultaneously, overlapping in seconds, reflecting each other, as a kind of intercommunicating levels of meaning, in which the cinema spirit chats and brings light into the darkness. At least Godard’s cinema spirit, which haunted his head crosswise. All five levels of consciousness are therefore not juxtaposed in parallel or even hierarchically nested, but rhizomatically intergrown/nested, at the same time feeding off each other, perpetually blurring and colorfully intermingling in chains of associations and cross-fades; simply levels of consciousness that speak to each other in echoes, even if they never understand each other. The spirit of cinema and its story(s), in which the gassed, emaciated corpses of the Holocaust make an appearance with the Marlboro Man and are counter-cut a little later in close-up of a vaginal penetration and the wildly laughing Pinhead Pip from Freaks.

It is the cinematographic equivalent of James Joyce’s belletristic word pusher “Finnegan’s Wake,” a highly complex monumental work peppered with neologisms and (foreign) wordplay, which is worked through word by word (in Godard’s case, image by image) and which likewise masters multiple levels of narration/consciousness by means of the language of the textual medium, articulating cultural as well as socio-political history in equal measure. Both works travel the walls of the nature of their arts and form a boundless experience in the recipient.

Histoire(s) du Cinéma is therefore a synapse blaster. Through montage and collage, the history(s) of cinema are transformed into a complex network of images, sounds, and quotations. It is as if one were in a panopticon, looking through a telescope that Godard constantly jiggles.

The episodes themselves are thematically subdivided, with this family inheritance intertwined with each other in chronology. For in the progression of the series, the births of the individual episodes, the genetic reference to the ancestors, the previous episodes, is taken up again and again:

(1a) Toutes les Histoires – – All the Stories: A look at the earliest childhood of cinema, which evolved from crawling to walking upright with the help of technological progressivity. At a time when cinema itself was seen as the heir to the visual arts and photography, while recognizing their cultural upheaval: In Hollywood as a dream factory and in the Soviet Union as a myth factory.

(1b) Une Histoire Seule – – One Story Alone: Cinema as a unified narrative, in which two handfuls of basic plots vary into genre-typical narratives and also evolve in tempo and showmanship, but are in principle locked into the same structure. It is also colored by film-theoretical and film-critical arguments that examine the medium with a dissecting knife and sketch it anatomically.

(2a) Seul Le Cinéma – – The Cinema Alone: This is accompanied by the question of whether the cinema is an independent art form at all or merely the extended arm of the visual arts, theater, literature, and music. On the other hand, it is also the shadow and light of contemporary events and the zeitgeist, with which it celebrates an unprecedented couple dance (keyword: documentary).

(2b) Fatale Beauté – – Fatal Beauty: The cinema as a place of seduction, where beauty and death can be fantasized at the same time (predominantly by men), above all in the being of the femme fatale. Images and sounds that are there to arouse emotions – both pleasurable and frightening.

(3a) La Monnaie de L’Absolu – – The Coin of the Absolute: One of the central and most understandable arguments within the Histoire(s). About in which reproduction quality the cinema confronts itself with the history and the present and in Godard’s conclusion the impotence of the cinema by the negligent, slightly resistant examination of the 2nd World War and above all the Holocaust – the (horror) event of the 21st century. Only Italian neo-realism was able to faithfully marry history and film and to tell it away with a militant revolutionary spirit.

(3b) Une Vague Nouvelle – – The New Wave: the most self-referential treatise, autobiographical remarks on his old gang. The Nouvelle Vague and its successes and failures for film history. In retrospect, the disillusioned struggle of some young men socialized by American detective story.

(4a) Le Contrôle de L’Universe – – The Control of the Universe: The Medium of Film as a Control Organ of Political State Organs. An ideal instrument for manipulating the masses using the example of the French Algerian War.

(4b) Les Signes Parmi Nous – – The Signs Among Us: Lastly, film is interpreted as an orchestration of (semantic) signs, even as a sign itself and not – like other media – as a command; a sign that one interprets, plays with, lives with. Cinema is the incomparable, powerful memory.

Conclusion

A must see.

Facts

Original Title

Length

Director

Cast

Histoire(s) du cinéma

466 Min

Jean-Luc Godard

–

What is Stranger’s Gaze?

The Stranger’s Gaze is a literary fever dream that is sensualized through various media — primarily cinema, which I hold in high esteem. Based on the distinctions between male and female gaze, the focus is shifted through a crack in a destroyed lens, in the hope of obtaining an unaccustomed, a strange gaze.

-

2 or 3 Things I Know About Her … or we know nothing.

What is it about?

If you want to be beautiful, you must not only suffer, but also prostitute yourself.

What is it really about?

2 or 3 things I know about her. Or also not know. And even more than just 2 or 3 things. She is a young Parisian woman. She is introduced to me by a whispering male voice from off-screen. She is Marina Vlady, actress of this film. She says, “Speaking is like quoting the truth” and turns her head to the right. This, according to the off-screen voice, has no meaning whatsoever. She is also Juliette Jeanson, the main character of this film. She says, “She has to get by somehow.” Here in this Paris of the late 60s. She turns her head to the left, which, according to the off-screen voice, has no meaning. The off-screen voice is Godard, the director of this film.

The obvious trinity overlays the conventional narrative: the director, the actress, the cinema; the Father, the Son, the Holy Spirit. Through the obviousness, the cross is placed on the shoulders of the spectator, as he equally perceives and passes on parts of this fiction in his reality.

In “2 or 3 things I know about her” the main character Juliette refers the image of young housewives of a bourgeois Paris. A Paris that is contradictory in itself, that is in a state of upheaval, which the director observes anxiously in his whispering voice. A devaluation of European social values through the valorization of consumerist, capitalist values, injected down the throats of a lateral-Atlantic nation with the help of Marlboro Coca-Cola. A nation simultaneously waging David vs. Goliath war with bloody feud at the end of the Pacific in a country called Vietnam.

Juliette’s world is only rudimentarily intertwined with the inhumanist events in Vietnam, but her life is in another guise of inhumanism: objectification, that is, the petrification of the subject. In the midst of tempting advertising posters for travel, fashion, cars, beer, a desire is awakened that passes from the human to the representational. You are what you have, instead of being what you think. Juliette already seems more and more transformed from subject to object. Despite her beautiful, Kirghizian face, it remains petrified and motionless. She moves her body sluggishly, laboriously through the shopping stores. Her voice rarely accentuates, rarely manages to sound out of the lack of emphasis. She will smile when a friend says to her: “Objects exist. And if we pay attention to you as people, it’s because there are more of them than people.”

She (and several other Parisian women and men) are put on display in this objectivist world. They present themselves for the presentation of objects. Juliette, it turns out, prostitutes herself for this during the day. Not to feed her family, but to be able to buy a new dress. For the acquisition of objects, she makes herself an object. How can this be better depicted than in a scene when Juliette meets with a suitor. In parlor, she asks him to avert his gaze as she undresses. When he mockingly asks why she wants him to, since he will see her naked in a few minutes anyway, she replies briskly, because she wants him to. The terse answer, however, hides the real reason: the removal of the clothes is the transformation from subject to object. This transformation must not be observed, because it would expose absurdity only inhumanistic way of thinking. And later, with an American suitor she will even wear a shopping bag of Trans World Airlines on her head because he is so wild about it. The face of Europe disappears while the body can be exploited.

The dilemma of subjectivity and objectivity extrudes not only from the view of the environment on the individual, but also in the inner life itself, the view from man to his environment: what is objective reality and what is subjective reality? The characters who have their say within this fiction do not know. They discuss it and do not discuss it. When they speak to another character, they also speak their thoughts aloud in the middle of the conversation, but only to us viewers. The other figure in the picture does not hear the thoughts. Thoughts of shame, of being overwhelmed, of sensuality. And when characters don’t speak their thoughts, they no longer have thoughts.

For Godard, cinema is, not only 24 times truth in a second, but language and image. Around both basic elements he lets his thoughts revolve audiovisually through the voices of his characters. For this he also makes use of Wittengestein and muses: “To say that the limits of language, of my language, are those of the world, of my world, and that by speaking I limit the world, I end it. And when mysterious, logical death removes these limits, there will be no question, no answer, only indeterminacy.”

This is the omnipresent burden of the main character in the film. To never be able to overcome the limits of her language, to be able to express herself intelligibly, in an advertising- and war-loud everyday life, whose prostitutive and consumerist events determine her thinking and feeling at all times and drive her further into loneliness. Into isolation instead of into a world where one can love and be loved. This is the empty future as an echo of the silenced past.

And this only applies not to the individual but also to cinema. It is not for nothing that Godard will proclaim the end of cinema a year later in Week End.

Conclusion

Wonderful real satire on capitalism and as a bonus: You don’t learn 20 or 30 things about her.

Facts

Original Title

Length

Director

Cast

2 ou 3 choses que je sais d’elle

87 Min

Jean-Luc Godard

Marina Vlady as Juliette Jeanson

Roger Montsoret as Robert Jeanson

Anny Duperey as Marianne

Raoul Lévy as John Bogus

What is Stranger’s Gaze?

The Stranger’s Gaze is a literary fever dream that is sensualized through various media — primarily cinema, which I hold in high esteem. Based on the distinctions between male and female gaze, the focus is shifted through a crack in a destroyed lens, in the hope of obtaining an unaccustomed, a strange gaze.

-

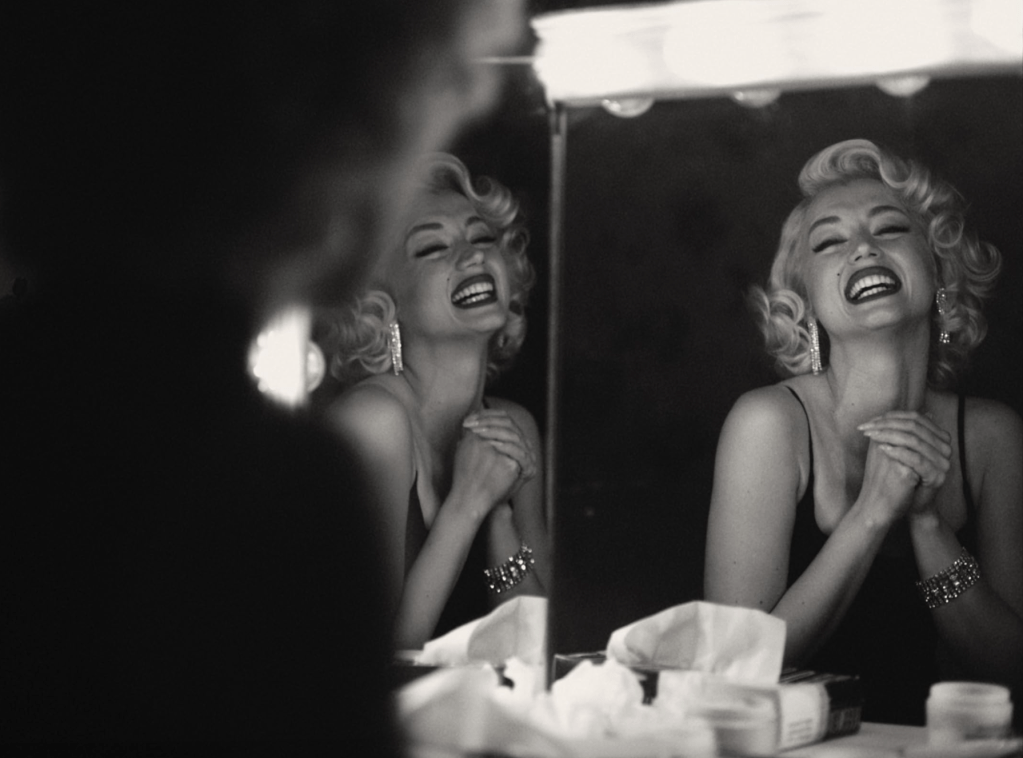

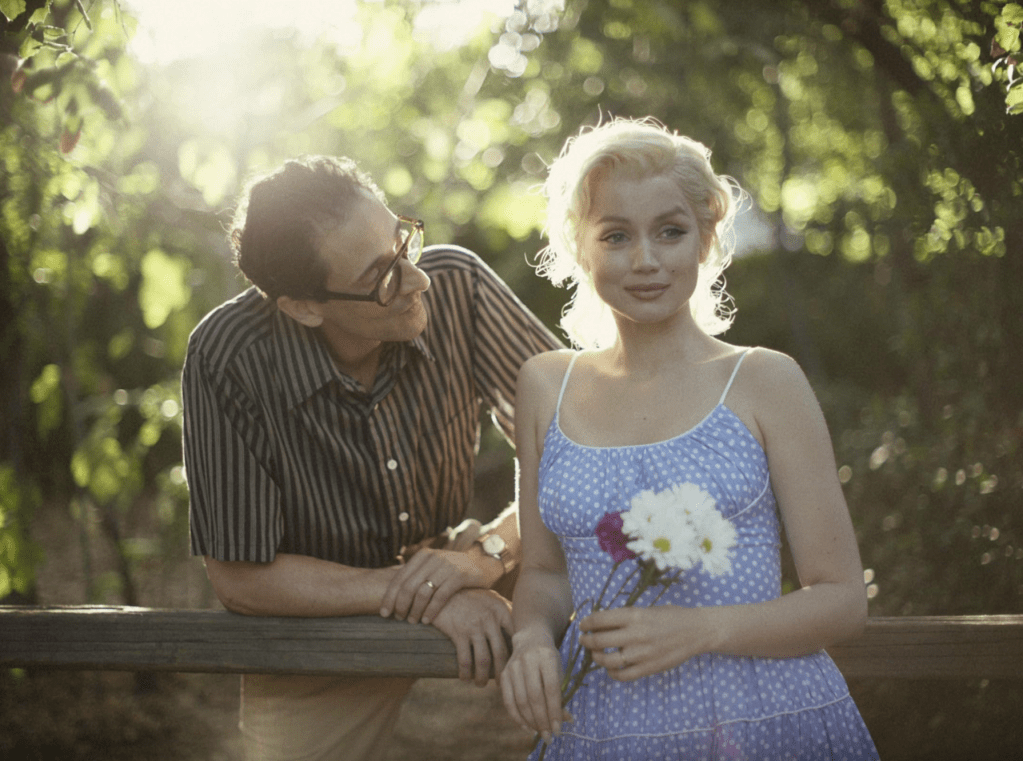

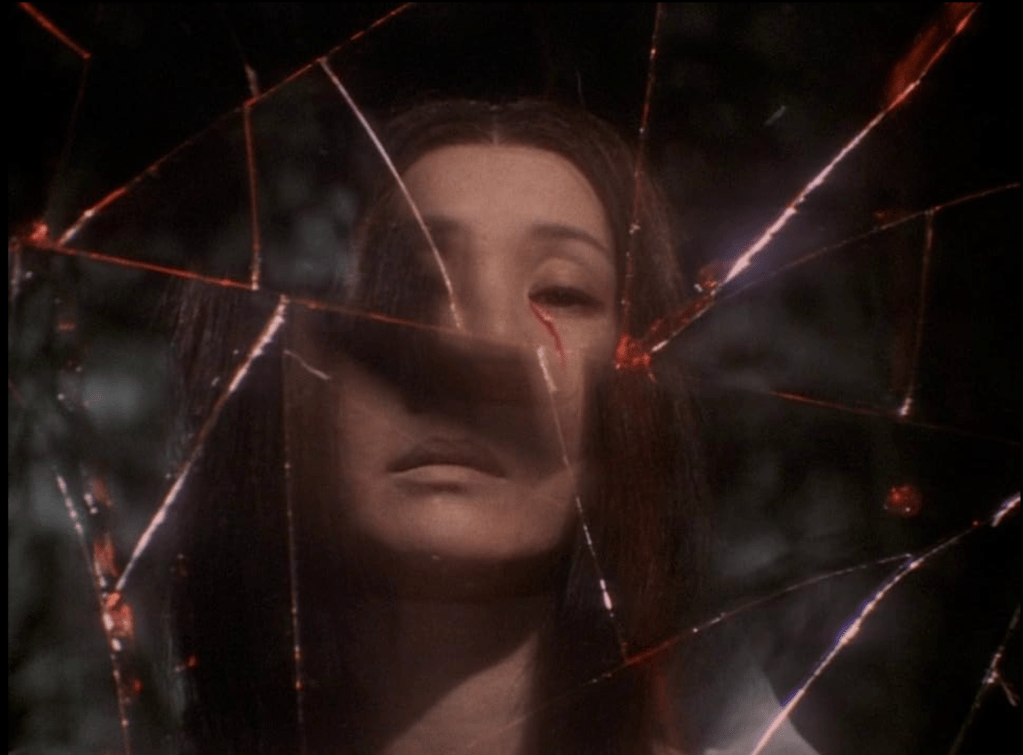

Blonde .. or Norma Jeane’s gaze.

What is it about?

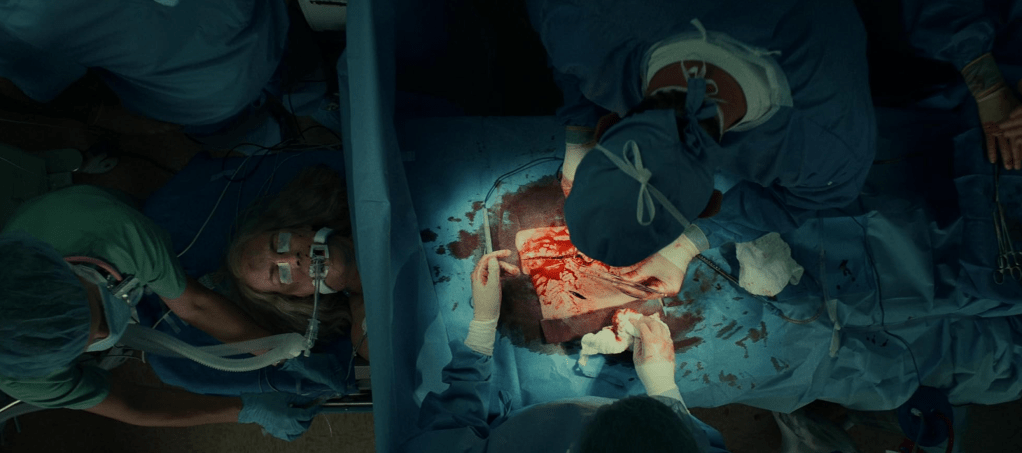

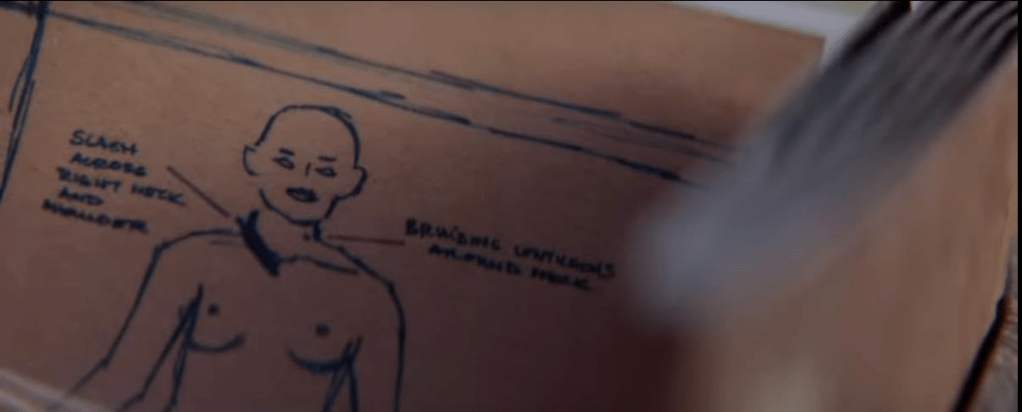

The misery-porn-like film adaptation of the novel of the same name by Joyce Carol Oates about Marilyn Monroe – from the disturbed view of Norma Jeane.

What is it really about?

What is Blonde about?

Put simply, Blonde is another big-screen adaptation of Joyce Carol Oates’ novel of the same name, which in turn is devoted to the life of Norma Jean Baker, or her poster-printed alter ego Marilyn Monroe.So is it a biopic?

Blonde is many things, but it is by no means a biopic in the usual sense. The stages of life the film stops at in almost hours are presented in an articulated and fictionalized way, beginning with the fatherless childhood in the violent hellfire of the schizophrenic mother, through the humiliating, repeated abuse by lust devils with the lever in power, the many, fruitless marriages, the shameful, blood-sucking abortions, and on and on.For whom is the film nothing?

Those who expect a historically accurate portrayal of the far too short life of Norma Jane/Marilyn Monroe will be brutally disappointed (by the way, it’s your own fault if you expect such a thing from biopics at all – – life is not a movie); just as those who hope for an ode to the icon Marilyn Monroe.This is not a romanticized, fan-pleasing interpretation of a public figure (unlike the unspeakable Bohemian Trashsody), nor is it a stodgy, Oscar-cheering carnival parade like Lincoln.

Blonde is different – and that’s what makes it so controversial.

What is Blonde, then?

“Blonde” is rather an associative concatenation of embarrassing life moments of a seemingly radiant icon whose career is revealed and exploited here as a soul-sucking nightmare. “Blonde” at least deals with the charming, glamorous, very self-confident being, what the figure Marilyn Monroe represents in our minds until today. It is rather an examination of the psyche of an unstable woman who, frighteningly enough, ended her life prematurely at the age of 36 (!) through a pill overdose. Anyone who bears this fact in mind cannot take the still existing public image of Marilyn Monroe, as we see her a thousand times in films and on posters, as the self-confident, strong and enviable woman. The myth of Marilyn Monroe is itself a fiction, a narrative that Hollywood has made us believe; that the press has made us believe and – even worse – that Norma Jeane, the real woman behind the costume called Marilyn Monroe, has made us believe.Marilyn Monroe is an artificial figure for stage lighting. It is not a human being. The human herself is named Norma Jeane. But what do we, who know only the artificial figure, know much about Norma Jean?

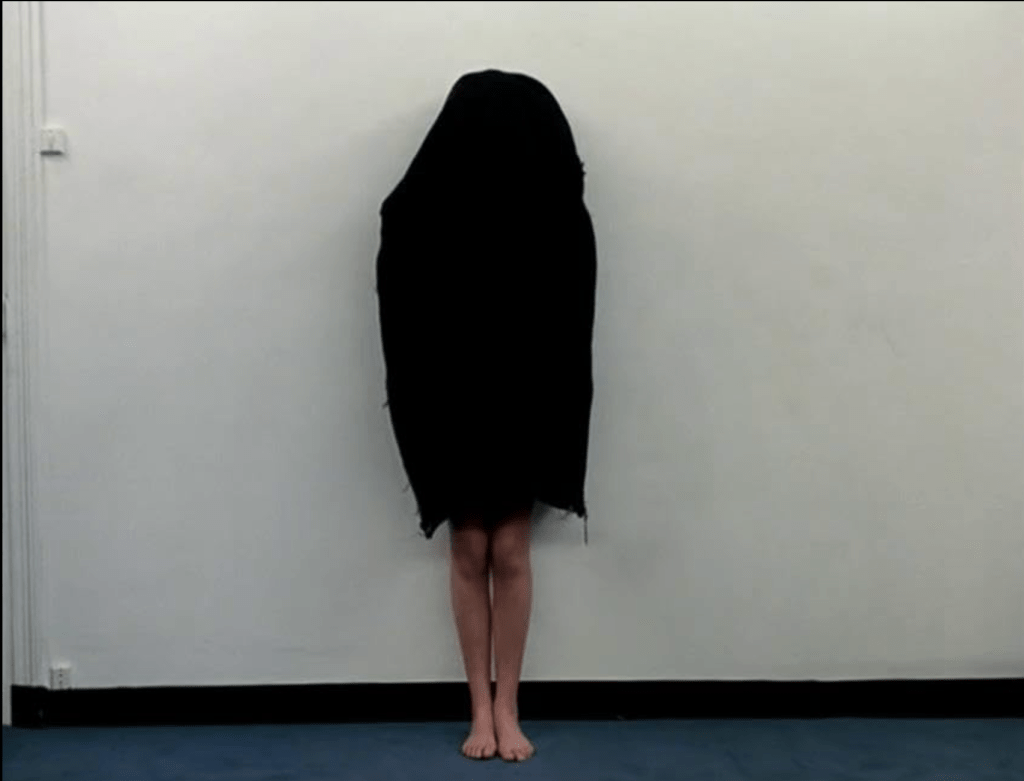

Andrew Dominik labors by all sorts of means to deconstruct the myth in challenging ways. He concentrates on capturing the Norma Jeane in “Blonde”, always hidden under the make-up, the graceful gesture, the quick-wittedness, the poster smile and the sequined dresses, who, as if from a prison (her body), witnesses all that happens around her and what in the flash no one perceives as a prison on her.

The camera penetrates through the body shell of Marilyn Monroe and retells the presumed soul life of Norma Jeane. In the film “Blond” we observe the woman known to us as Marilyn Monroe trying out for a casting in a completely insecure and fragile way, this insecure performance does not reproduce the original casting, but only Norma Jeane’s inner life during the casting. Thus, the interior is put on display and not what we already know as a facade; the untidy inner life emerges. In the introspective portrayal, we see what the then Norma Jeane suppressed in the universally beloved role of Marilyn Monroe, but what was rumbling inside her. Thus, in the scenes one never sees the femme fatale-like, witty and self-confident sex bomb Marilyn Monroe, in other words: not the art figure, but the troubled, insecure Norma Jean, the interpretation of the human being behind the art figure, who helplessly witnesses everything in the split body.

Therefore, watching the film under false premises and expecting more of the glamorous life of a Marilyn Monroe inevitably leads to disappointment and anger. This is not a film about Marilyn Monroe. It is an interpretation about the fragile soul life of Norma Jean. To make matters worse, it is not a portrait reflecting the highs and lows of her life, but only the perpetual suffering. It is: The Passion Monroe. Or no, it is: The Passion Jeane.

And does this concept work at all?

Yes and no. The first half hour annoyed me. I found it incredibly exhausting to have to watch the constantly howling and whispering Ana de Armas as Marilyn Monroe and how only bad and repulsive things keep happening to her from all sides. Abuse, repudiation, rape, auto aggression. As a viewer, I screamed at the TV, yelled at it that I understood that she was in a bad way, but that I would like to see something of the Marilyn Monroe that is commonly known from movies and TV. I had to accept, however, that Andrew Dominik does not want exactly that. With the idea to see here really only the interpreted inner life, I could bear the film far more.Nevertheless, so I find, the eternal suffering carries hardly over the entire running time, because again and again I feel as a spectator nevertheless only half-baked, one-sidedly involved. I can hardly imagine that Norma Jeane was a constantly broken, desperate and unstable woman as she is shown here. For it is also clear from reports that she was extremely well read and therefore had sufficient quick wit to be able to use situations to her advantage; likewise . This aspect of her person emerges only in the smallest moments.

As a result, the constant barrage of agonizing moments without highs and lows becomes a test of patience that offers little new with each successive scene of suffering and narrates each plot in an extremely predictable manner. Furthermore, the film tortures with sometimes flat monologues and dialogues; for example when her mother drives through a fire smoke and comments “I can’t see anything”. There are, unfortunately, countless examples of this, culminating in a brief but absolute low point in the final, in itself splendidly nightmarish third: the encounter with John F. Kennedy.

What I still could never quite come to terms with was the oversized portrayal of her alleged Electra complex, the father complex.

Electra complex?

In “Blonde,” Norma Jeane is psychologized with a hefty load of Daddy-isms. “Daddy,” a big Hollywood producer according to her mother, is the one Norma Jeane takes it all on for. He’s the one she actually wants, to finally have a father. Andrew Dominik supercharges this longing in constantly whispering daddy purrs, in imagined dialogues with her father, who observes, appreciates and also punishes her public image like God the Father. She also addresses her much older husbands as “Daddy,” as if they were the reincarnation of the father (even if these Daddy-names are also just internal processes, they feel very alienating and trying).Admittedly, it fits into narrative that the woman who longs for her father ends up in the early days of her career with, of all people, two young men who suffer from the fame and violence of their acting fathers – namely Charlie Chaplin Jr. and Edward Robinson Jr. However, while they envy Marilyn for not having a father and thus being free, their approach to her is an attempt to reach the lost father in the young men, as young images of great Hollywood acting fathers.

And certainly Andrew Dominik opens Daddy also only as a metaphor for Hollywood itself to wrap, after all, it is Hollywood in whose patriarchal arms she has gone and suffers nothing but abuse, but prefers this paternalistic abuse than to get no attention from the “father” at all.

How is the play?

After reading praise everywhere about Ana de Armas acting in “Blonde”, I do have a controversial opinion here: I find the mimicry far too theatrical and exaggerated. Not for a second do the eyelashes and corners of the mouth remain still, there is always a lot going on in her face. Too much for my liking. I had the feeling I was watching an actress act.What makes the film worth seeing?

Despite all the criticisms that blow over the film like a storm and which, in my opinion, are mainly due to the partly weak screenplay, one rock remains standing in the surf: The impressive camera, editing, sound and lighting work. “Blonde” is as stunningly aesthetic cinematographically as the myth of Monroe herself. The glamour and turbulence of her life is elaborated through all sorts of cinematic gimmicks: Changing aspect ratios, color and black-and-white imagery, match cuts, out-of-focus, merging bodies, interior body shots. The elegiac soundtrack by Nick Cave & Warren Ellis musically underscores the scenery as a ghost story.The radical and I would even say: for such a budget experimental staging is reason enough to give the film a chance.

Love it or hate it?

The film is divisive and incredibly stimulating to discussion, not so much about Norma Jane/Marilyn Monroe per se, but rather how she could, should, and ought to be portrayed. I am extremely conflicted. The absorbing production, with few exceptions, took me deep into the abyss of her life, into the psychological terror and nightmare that the real Norma Jeane must have had to endure inwardly and alone at the time, and broke from it – far too soon – while her mythological appearance did not reveal a single worry line or tear. I am therefore also grateful that Andrew Dominik has chosen a different way to interpret Marilyn Monroe.

Conclusion

Neither flop nor top.

Facts

Original Title

Length

Director

Cast

Blonde

167 Min

Andrew Dominik

Ana de Armas as Norma Jeane/Marilyn Monroe

Lily Fisher as Child Norma Jeane

Vanessa Lemonides provides Monroe’s singing voice

Adrien Brody as The Playwright, Arthur Miller

Bobby Cannavale as Ex-Athlete, Joe DiMaggio

Xavier Samuel as Cass Chaplin, the son of silent film icon Charlie Chaplin

Julianne Nicholson as Gladys Pearl Baker, Marilyn Monroe’s mentally unstable mother

Evan Williams as Edward “Eddy” G. Robinson Jr.

What is Stranger’s Gaze?

The Stranger’s Gaze is a literary fever dream that is sensualized through various media — primarily cinema, which I hold in high esteem. Based on the distinctions between male and female gaze, the focus is shifted through a crack in a destroyed lens, in the hope of obtaining an unaccustomed, a strange gaze.

-

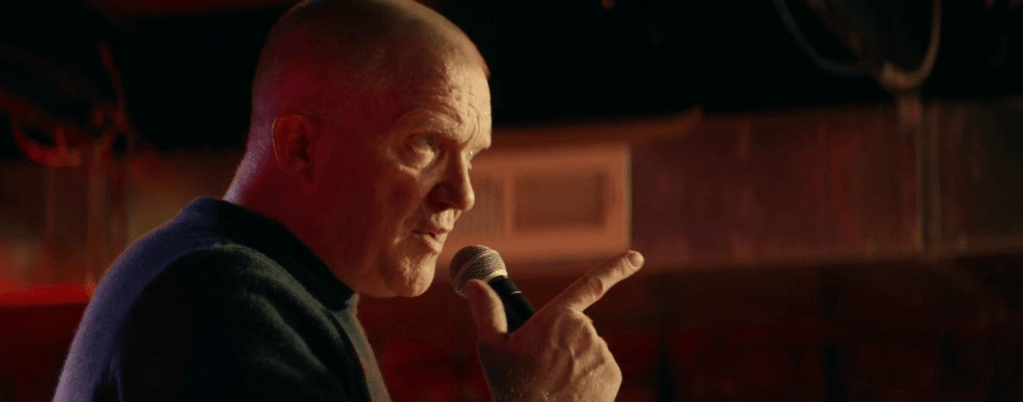

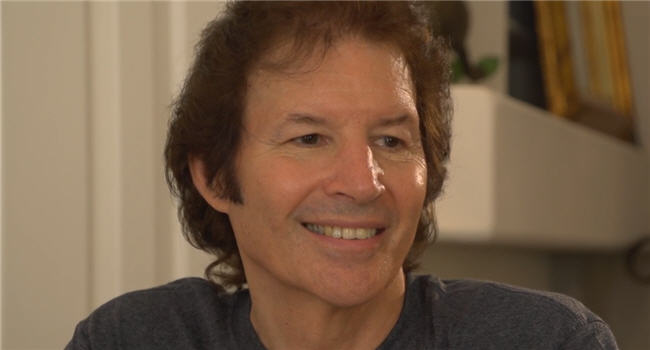

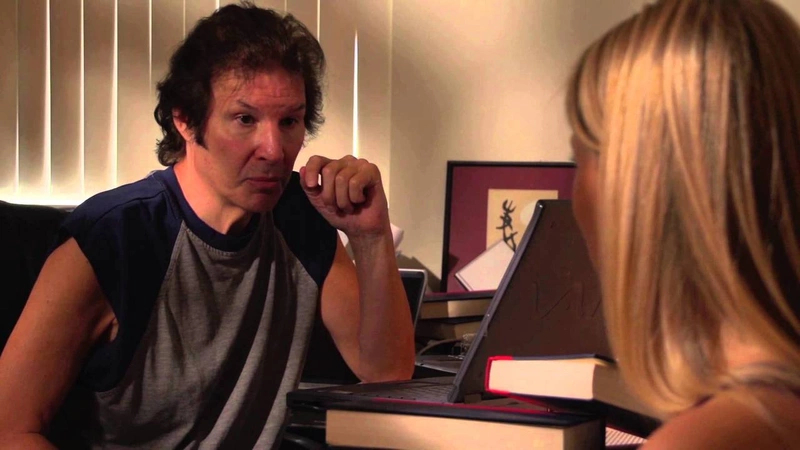

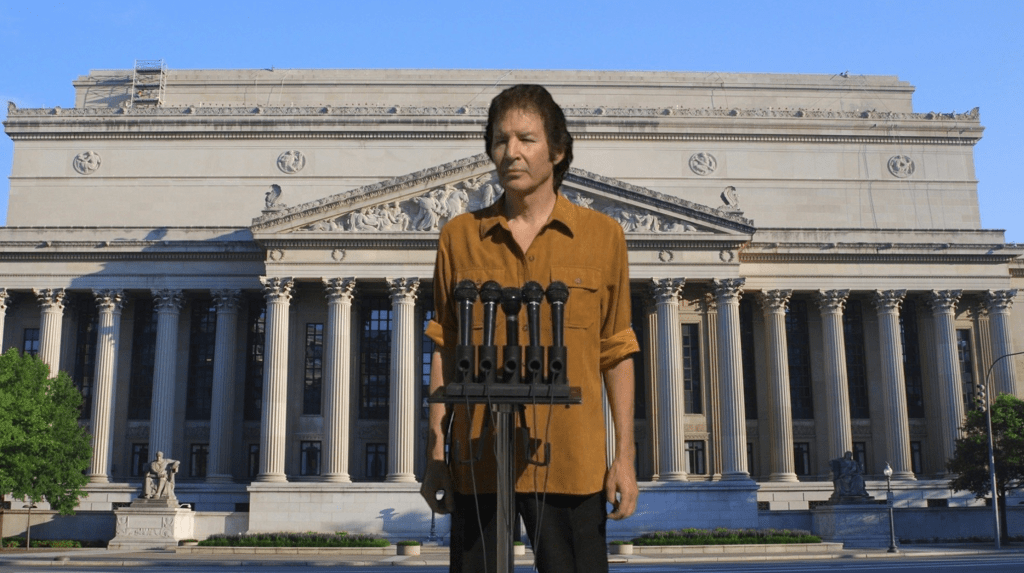

Fateful Findings .. or Finding Perfectness.

What is it about?

It’s Neil Breen being Neil Breen doing Neil Breen things.

What is it really about?

When I suck on film tapes in broad daylight and in the dark of the evening, it either tickles my tongue so bitterly that a wrinkle-throwing grimace cuts across my face or so sweetly that I disappear into the candy-colored land of milk and honey.

And then there are unique film tapes, cut somewhere beyond heaven and hell, there tickles not only the flesh-colored mouth lobe, nope, pff, there it explodes in the whole mouth area, as if a big-bang, light, all-scorching fireworks go off, whistling all the way to the nasal cavities and from there, hissing all the way to the nerve-housing cauliflower called the brain apparatus, settling in there and waiting to be tickled daily. It shakes and twitches, and suddenly – if you don’t pay attention for a second and the moon smooches the sun in a moment of tireless lust – the ceiling of the room rises to the floor and the floor blocks the front door, from which the mind still quickly escapes never to be seen again.

Fateful Findings is just such a spectacular marvel, peeled from the one true world egg after being hatched under the armpits of a common house sparrow, to be captured on the precious plastic skin layers of a film tape over 2,000 long. A work of art, a child, the brood conceived by God in drunkenness with Yog-Sothoth himself. So unimaginably brilliant that it splits the spectators like a hatchet splits the heads of those very spectators. A cursory glance between two half-opened windows reveals to the left and right eye: 31% of the letterboxd locos are pure, creampuffed, cheese-headed cinema heretics with their 0.5 star “ratings”, while at least 28% stand by good taste: upright and steely, with proudly smoldering chest, with adorable salute to the rising sun instead of the end of the world behind the curtain.

I’ll provocatively step into the wrestling ring (you’ll recognize me by the cardboard box on my niche and the red rose pinned to my lapel) and proclaim: Only those who really deal with films extensively can properly classify, process and appreciate Fateful Findings. Whoever has a different opinion (pah!) should get into the ring and compete against me. But mind you: I have Neil Breen on my side. Your victory is hopeless.

Neil Breen. Director of Fateful Findings. Producer of Fateful Findings. Screenwriter of Fateful Findings. Lead actor. Editor. Production Designer. Set Decorator. Make-Up Department. Sound Department. Casting Department. Costume and Wardrobe Department. Location Department. It is the omnipresent film grain that lights up the audience here in 24 frames per second. Each frame pulses in sync with Neil Breen’s heartbeat. The film reel wears the same bird’s nest hairdo (and therefore rattles as it circulates in the projector). The sound buzzes in the same mouthful.

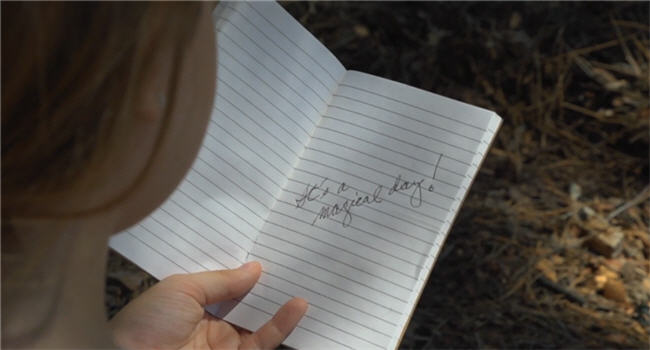

For the life of me, it’s impossible to fathom what the one remaining demigod Neil Breen is unleashing on humanity here. This is the cinematographically manifested inner life of a highly stubborn man who is deadly serious about everything in Fateful Findings, and for that reason alone leaves the audience drunk as the credits roll. With a story so diffuse and incoherent that in the middle of it I didn’t even know what my name actually was or what the 2nd derivative of the function f(x) = sin(x – 5)^2 is. It’s a story that avoids those well-worn and worn paths of sweaty Hollywood boots, preferring to trudge through the wild jungle that no one else dares to trudge through, for good reasons. With unique dialogues that shred past each other, always repeated as if characters were demented or five years old. With dialogues that repeat themselves and are therefore repeated all the time. As dialogues. A film that is not only about magical days (“It’s a magical day!”), but presents one magical moment after the next. Really, every scene is magical. Every scene! From the very beginning, you sit there with your mouth open to give air to the fireworks, of course, but also from pure amazement and – – – horror.

The greatest astonishment and – – – horror emanates from Neil Breen’s steely earnestness, which makes even tempering steel melt with delight. His films stand apart from (intentionally) badly made garbage can fare á la Sharknado and Mega Shark vs. Giant Octopus precisely because Breen’s films are never ironic, never tongue-in-cheek. If a Scorsese film is a masterfully decorated, flavorfully tweaked pastry, while Asylum films are the frozen version of a Coppenrath & Wiese discount, Neil Breen films are a wax crayon drawing of a cheesecake, scribbled blindfolded and with a candy cane chewing mouth, which Neil Breen would tirelessly claim is, of course, a delicious cake.

It’s simply incredible that Neil Breen doesn’t notice in the slightest that his films aren’t treats of award-winning patisserie. This idiosyncratic unreality, however, lures a fascination of unimagined proportions from the blockbuster-accustomed brain areas. Shy but encouraged, this fascination fights its way along the dusty brain pathways to rise in perfection of form as a star on the horizon of the film mind. One’s own world view is shattered thanks to the memorable film images of Fateful Finding, compressed into a lump, further sliced with the scalping knife, impaled with the pitchfork, to finally be heated on a silver spoon on hot bulb light of the projectors and consumed in the ramble of paradigmatic starvation. To feast on this bizarre experience while otherwise redigested is chewed over and over again is to discover the love of film.

And I promise, as I’m still standing here in the wrestling ring (careful not to get strangled by my billowing cape), after seeing this movie, you won’t see movies the same way again.

Conclusion

It’s Neil Breen being Neil Breen doing Neil Breen things.

Facts

Original Title

Length

Director

Cast

Fateful Findings

100 Min

Neil Breen

Neil Breen

Neil Breen

Neil Breen

Neil Breen

What is Stranger’s Gaze?

The Stranger’s Gaze is a literary fever dream that is sensualized through various media — primarily cinema, which I hold in high esteem. Based on the distinctions between male and female gaze, the focus is shifted through a crack in a destroyed lens, in the hope of obtaining an unaccustomed, a strange gaze.

-

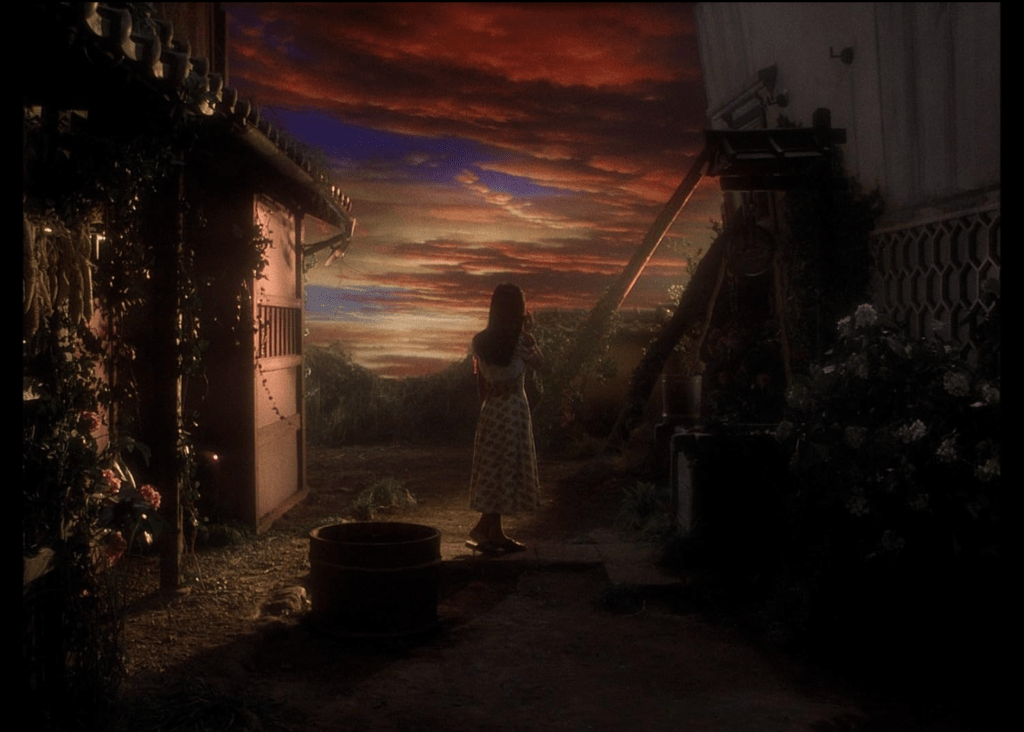

Hausu .. or the magic in cinema.

What it is about?

A group of young schoolgirls visit and old lady, her suspicious cat and her murderous haunted house. There they leave puberty behind and grow up … or else they are eaten by a piano.

What is it really about?

Once upon a time there was a Japanese director. His name was Nobuhiko Obayashi and he was also the father of a 10-year-old daughter. One evening, as the cherry blossoms began to sprout from their buds, two men from the Tōhō palace in the big city came to the home of Obayashi and his daughter. Father and daughter gave the rain-soaked men food and drink, and the men reciprocated with great thanks, handing over a heavy sack of golden thalers. “Make us a movie,” the first man said to Obayashi. “A movie like Jaws, and then make this sack of thalers into a truckload of thalers.” The second man gave him another hint, “tapping the thalers three times brings good luck and rain of ideas.”

Even before the sun rose over Mount Fujijama, the men disappeared into the mist. When Obayashi’s daughter awoke from restless sleep, and with honeyed mouth at morning hour she told her father about her strange, even bizarre dreams, the cherry blossoms began to bloom in eye-opening splendor: “Daughter, shake and shake, throw all your ideas over me!” Immediately the ideas gushed out of his daughter, dreamlike tales surging in unfathomable beauty of childlike innocence. Attentively and quite proud of his daughter, he listened to her imaginative tales. With each of her words were painted paintings full of nostalgia, childlike anxiety and carelessness. When the daughter was tired and exhausted from talking non-stop, the father announced on the empty-swept streets, “Such great ideas of his daughter, oh sure, he always shoots something better than Jaws”.

The days passed, the moon patted the sun’s limp shoulders, and as the last cherry blossoms were carried across the land by the wind, the Japanese director, as prompted by the two men, began to make a film called Hausu. About a ghost story that spoke from the pure youthful heart of his daughter. It is about a young sixteen-year-old named Gorgous. Many years ago, her mother was lost. A long-awaited summer vacation with her father is about to begin, to step out of the mountain shadow and climb to the sky-lit top of the world. But surprisingly, her father became involved with another woman; a woman so beautiful and graceful looking that even the mirror on the wall marveled at her brilliance from the fairest in all the land.

The Japanese director thought about how he should realize this cinematically and made with the talers knock, knock, knock, so the ideas bubbled out of his head: hand-painted backgrounds as if from picture books; he created with the strongest light bulbs of Japan completely overexposed moments in which the white silk sheen shone over the porcelain-like stepmother’s face ghostly and divine at the same time; cross-fades from small portrait-like image sections to large shots. Alternating as if the images were having an epileptic fit, or playful, like a child trying out the thousand and one buttons of a new toy. Then he continued with the rest of the narrative.

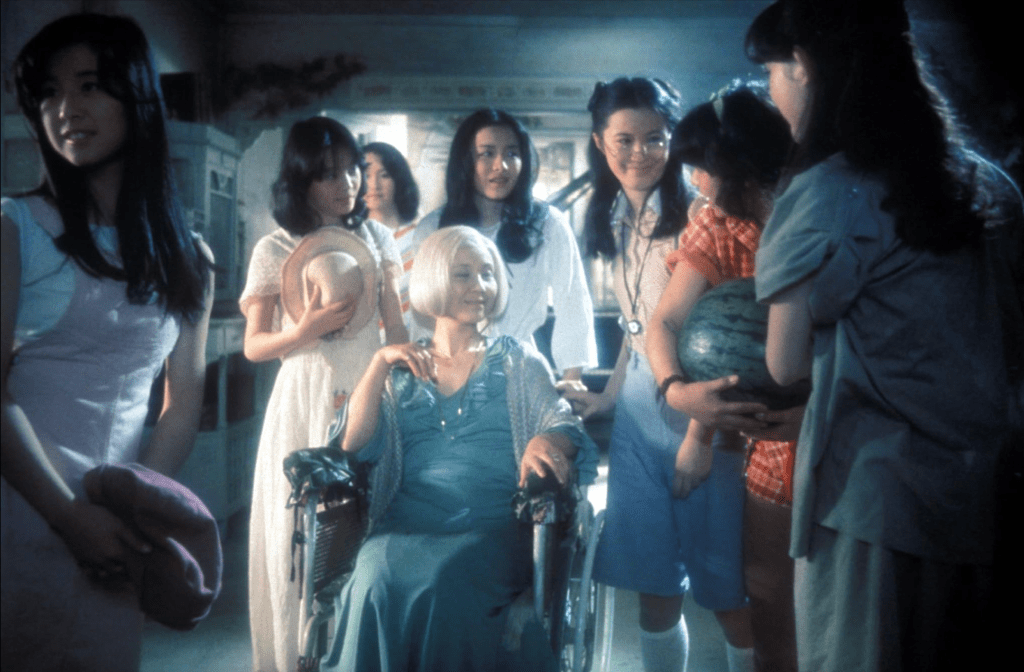

The young Gorgous decides not to go on vacation with the ole step-witch and instead to visit her aunt, the sorry sister of her deceased mother. Together with her friends Fanta the dreamy one, Kungfu the martial arts girl, Gari the analytical thinker, Sweet the loving heart friend, Melody the piano player and Mac the gluttonous all-in-one stuffer she sets off. So the seven girls set out on the rocky road to seek out their lonely, widowed aunt behind the seven mountains while playing all kinds of jokes.

The Japanese director thought about how he should realize this cinematically and made with the talers knock, knock, knock, so again the ideas bubbled out of his head. So he dedicates a performance to each of the seven girls, true to their namesake trademarks; for example, Melody, who strums melodies with her fingers over piano keys, or Mac, who can always be seen munching on buns or other food (like stomach). The journey itself is shown in an animation sequence of a train, after the girls board the train and the camera enters a boy’s picture book presenting that very train. The fate of the aunt is told to a subsequent flashback, embedded in old-fashioned, sepia-toned images and commented on by each of the girls, sometimes humorously, sometimes empathetically. Then he continued with the rest of the narrative.

With apparent kindness of heart, the aunt takes in the seven girls to her crunchy little house. But the dubious smile on her gray-haired, wrinkled face betrays that this visit means for her: seven at one stroke. The aunt’s hospitality turns into sweet and sour doom.

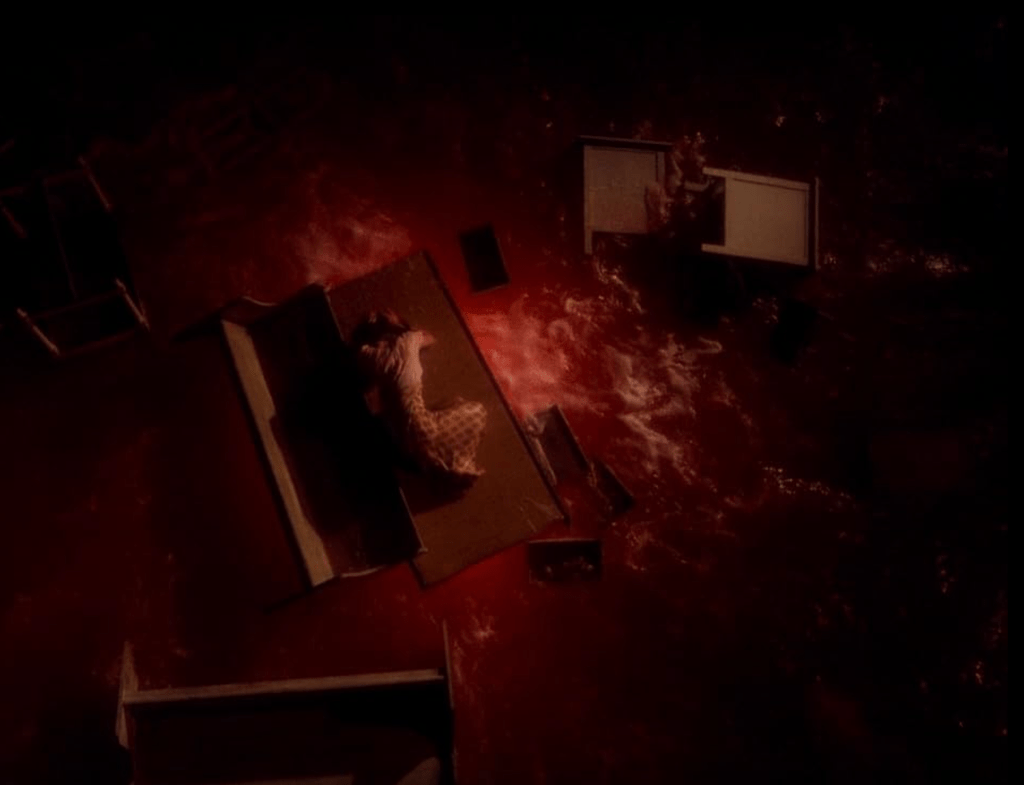

The Japanese director thought about how he should translate this into film and made knock, knock, knock with the talers, so the further ideas bubbled out of his head: A cat from which lightning shoots; eyeballs that rotate in mouths; the head of a decapitated girl floats out of a fountain and bites a friend in the rear; another like a mirror shatters into thousands of shards; another friend first has her fingertips bitten off by a piano, then her hand, and finally the piano swallows her whole; another girl is transformed into a living room chandelier. This is accompanied by the piano notes of the nursery rhyme leitmotif. Then he continued with the further narration.

Soon it becomes clear that the aunt and her crunchy witch house are for all the outlandishness. Even with the help of her otherwise only roommate, a cat that can not only open doors, but also close them. By feeding on innocence and youth, the aunt is able to rejuvenate herself to the best age of her life. But the memories of youth, first love, and her first husband, whom the war ate and spat out belching, gnaw at her soul-eatingly, so that she now feeds on souls. Gorgous, too, disappears not only into the aunt’s organic haunted house, but equally into the tragedy of the aunt herself, becoming part of this world of grief and eternal disappointment. Then also in the apparent redemption when the stepmother finally comes to visit.

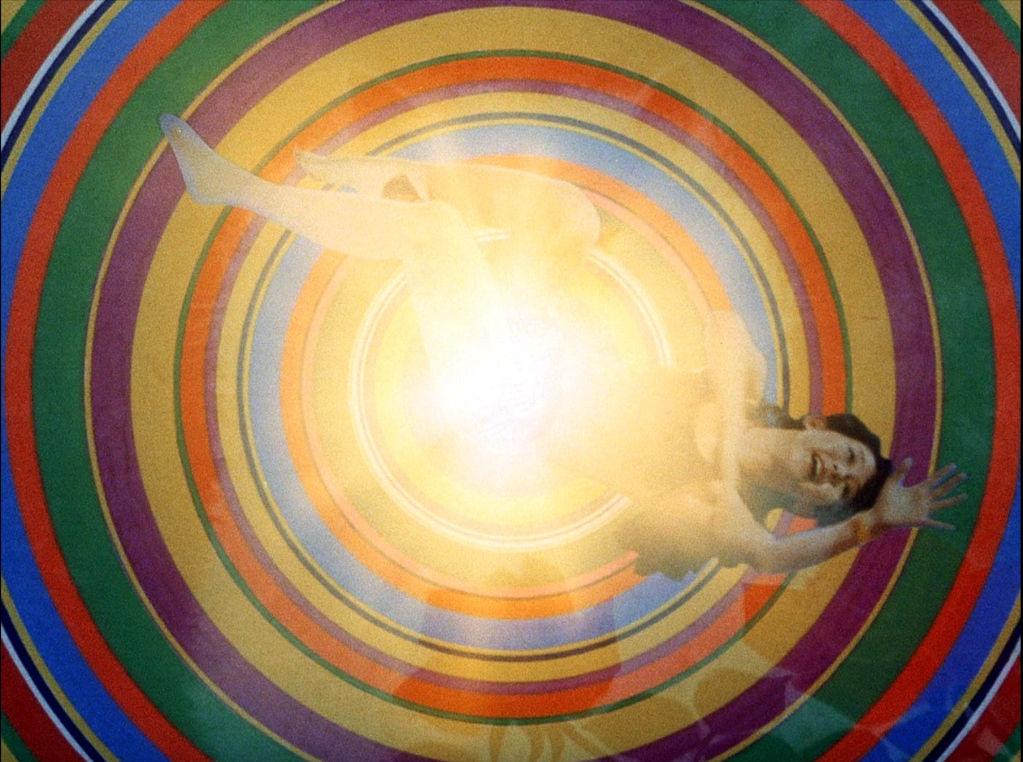

The Japanese director pondered how to make this cinematic and made with the talers knock, knock, knock, so the last ideas bubbled out of his head: people transformed into bananas; in the meter-high dammed up blood pools; graphics that gyrate in cut-out techniques; the constantly scurrying around and watching grumpy pussycat; sunset shots as in an advertisement for champagne. It’s as if the director is hollowing out the film images using silhouettes and flooding in color-overloaded scenery. KAs if there were only this one film in which he could immortalize all his ideas, no matter how bizarre or crazy.

This was the story, fed by the daughter’s ideas, which enraptured the father as much as a sweet particle on a late summer autumn afternoon. Certainly it is also said that during the shoot the father pranced around the projector light and spoke, “Oh, how good it is that no one knows I shit on film rules.” At a time when Japanese traditional cinema with its traditional film rules was buried under the earth dredged up by Hollywood. So the director, with the help of his daughter, raised Japanese cinema to an incomparable ascension. Pulled upward by the winds of a frenetic and avant-garde playfulness, the knock, knock, stuffed with infantility and innocence.

And although at the box office the sack of thalers turned into a truckload of thalers, bringing the director and his daughter much good fortune and creative frolic, the critics outside the movie theaters vomited with the words: junk, junk, junk, the Japanese art with it forever away.

But even if the pithy critics have died, the cult of Hausu still lives today.

Conclusion

A bizarre fairy tale about growing up.

Facts

Original Title

Length

Director

Cast

Hausu

88 Min

Nobuhiko Ôbayashi

Kimiko Ikegami as Oshare

Miki Jinbo as Kung Fu

Kumiko Ôba as Fantasy

Ai Matsubara as Gari

Mieko Satô as Mac

Eriko Tanaka as Melody

What is Stranger’s Gaze?

The Stranger’s Gaze is a literary fever dream that is sensualized through various media — primarily cinema, which I hold in high esteem. Based on the distinctions between male and female gaze, the focus is shifted through a crack in a destroyed lens, in the hope of obtaining an unaccustomed, a strange gaze.

-

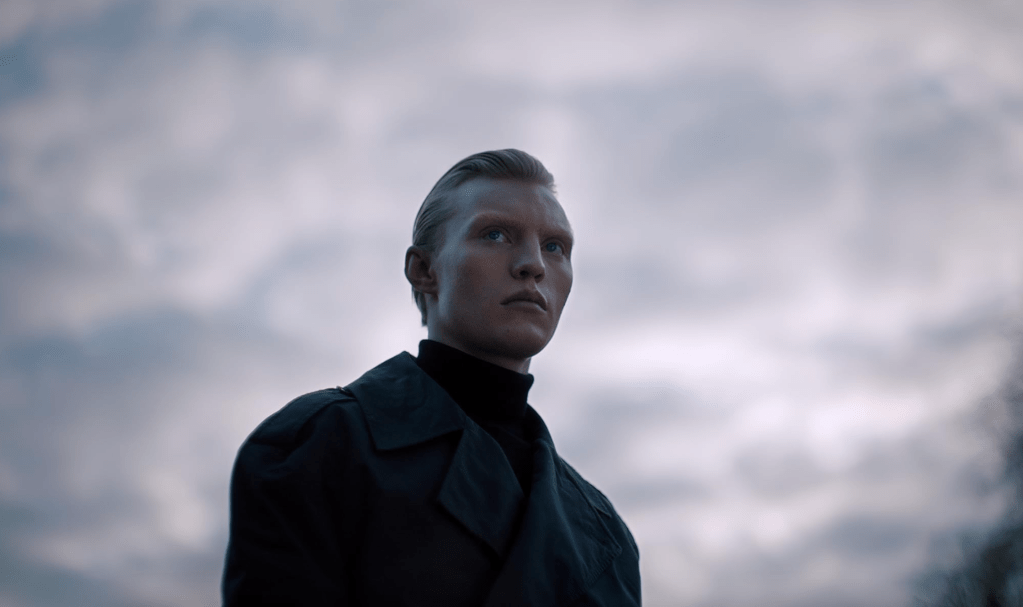

Copenhagen Cowboy .. or a european Western with a cowgirl.

What is it about?

A young woman, in the midst of Albanian traffickers, pigs, the Triad and vampires, kicks ass.

What is it really about?

Copenhagen in the title, but Copenhagen only touching the edge. Accompanying women and men who roam the fringes of society. At these, a genderless stranger is pushed into the foreign. A genderless under sexist: lepers in abandoned farms and slaughterhouses. With men who are not only pigs but also grunt and squeal. The slaughterhouse now a brothel shed, where forced prostitutes are benched, whip-whipped by small-town Albanian gangsters who make the medium-size killing. For bling, with which the whorehouse mummy decorates her withered neck. A childless saddleback who wants to have a son or daughter, but only gives birth to dead embryos between her legs.

The protagonist, the stranger among strangers, is supposed to help her to personal maternal happiness. Miu. An elusive, mystical being. Lucky charm for one and a lucky robber for the other. Unassuming and tomboyish, she wanders these Danish, stinky ethers. With pageboy cut and in her tracksuit that hides any feminine curves, she observes. Studies the lunatics and the lost around her. In her gaze, her a deeper soul level seems to reveal itself. As if she could glimpse the essence of every human being. A post-modern heroic figure, Joan of Arc of the 21st century. With armor made of cotton and polyester instead of tin. From episode to episode from sweater, to vest further outfitting. Blessed are her hands with supernatural abilities to bless. Is she a ghost?, she asks a Chinese woman. She meows in response to the question. In China they eat dogs and cats protect from evil spirits. Meow. Meow. Meow.. Me you. A cat among pigs, eating men who are pigs. Everything eats itself.

But the Albanian small-town gangsters and the madam is devoted only in miniature. The loose hanger that is left hanging. The big picture lurks in a vampiric aristocracy and the Chinese triads. One phallus-worshipping bloodthirsty and bloodthirsty; the other migraine-ridden and reverent and neck-breaking. Both with cold blood in their veins and therefore warmed by foreign blood on their cold hands. A revenge plot builds, reaching from the dreary setting of suburbia to the night-lit metropolis of Copenhagen. An elusive, ever-meandering narrative, a watered-down narrative flow. Shuttling from plot bank to plot bank, eroding the watery narrative ground, shallowly dragging along the detritus of hours past. A multifaceted divergence and blurring of plot structure to motivically cast revenge, masculinity, femininity, family, penises, pigs, honor, bloodline into a serialized, dreamlike monument. In stretched time, because everything stands still. No progress, no advancement, only stasis.

The opaque, fleeting bustle entirely incorporated into tablaux vivants. The cinematic still life of inanimate human objects. 360° camera pans. Observing like a stranger observes strangers. Hyperaesthetic, contemplative panoramic view. A panorama in miniature. Far from the gigantism and vastness of a Los Angeles and Mexico. With fabulous episodes and moments that burst into the hypothermic world of Copenhagen. Set in stinking, auditory squeaky-quiet pigsties. In dank basements where young women are kept like pigs in fattening without their IDs. Behind them, condescending floral-patterned wallpaper and pebbledown plaster. Woven in like flowers in the hair, growing and blooming over the face. Plucked last as a white rose. The symbol of hope and sorrow in Chinese tradition. A bud that opens magically. The flower head on the prickly body that stings other bodies. Drops of blood staining the white, the innocent, for the power-hungry to feast on. At last, the enjoyment of innocence. A duel with fists and kicks, in a soundtrack from other worlds.

Melodies and rhythms resound feverishly and pulsatingly. The sensual background to highly stylistic images. The sound makes the music and the image speaks over the music, which screams at the viewer, whispers to him, takes him on a unique hero’s journey, douses his eyes and ears with sugar, and at the same time pushes him into a comatose, nightmarish state.

This is Copenhagen Cowboy and this is series of a man who claims to see himself in contact with aliens. Yet he seems like an alien himself. His way of using genre-typical iconography, breaking it up conventionally and patching it together again into an unusual pattern is just as alien.

Conclusion

Audiovisually highly impressive. The content is exactly what you love about Refn’s stories: blood and revenge.

Facts

Original Title

Length

Director

Cast

Copenhagen Cowboy

312 Min

Nicolas Winding Refn

Angela Bundalovic as Miu

Andreas Lykke Jørgensen as Nicklas

Li Ii Zhang as Mor Hulda

Jason Hendil-Forssell as Chiang

Hok Kit Cheng as Ying

Shang Thingsted Laursen as Lai

Emilie Xin Tong Han as Ai

Zlatko Buric as Miroslav

Fleur Frilund as Jessica

Valentina Dejanovic as Cimona

Maria Erwolter as Beate

Ramadan Huseini as Andre

What is Stranger’s Gaze?

The Stranger’s Gaze is a literary fever dream that is sensualized through various media — primarily cinema, which I hold in high esteem. Based on the distinctions between male and female gaze, the focus is shifted through a crack in a destroyed lens, in the hope of obtaining an unaccustomed, a strange gaze.

-

La Chinoise … or The Ambivalence of Politics.

What is it about?

A residential community of far-left students wants to initiate communist revolution. Unfortunately, they disagree and begin to rebel against each other.

What is it really about?

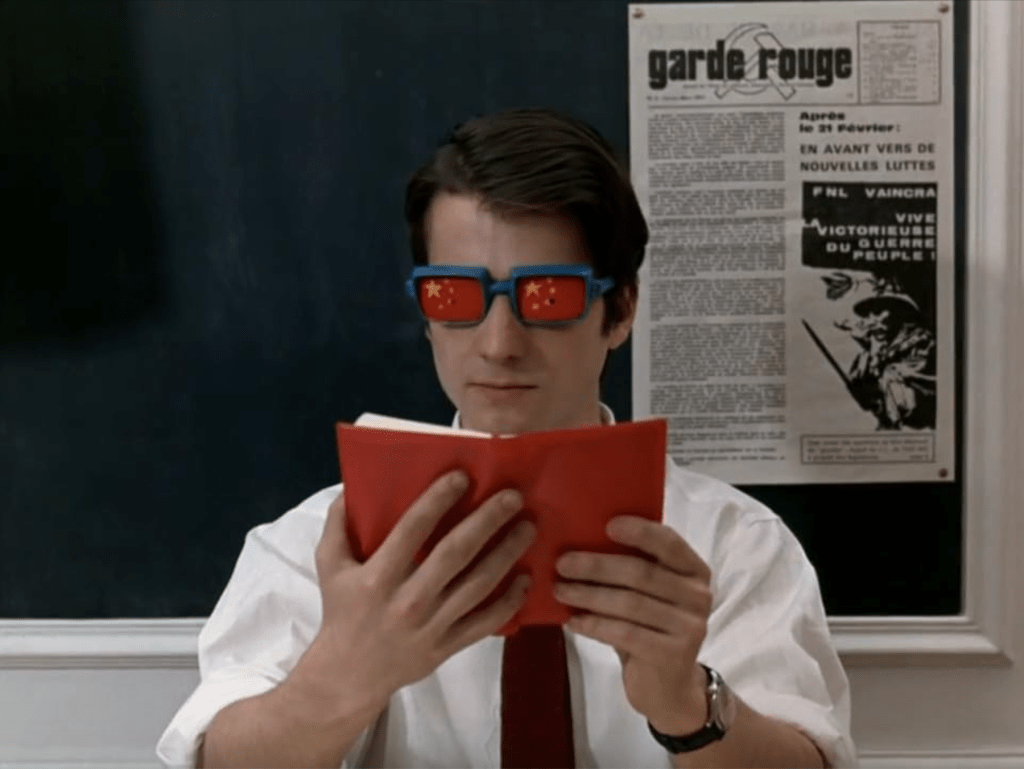

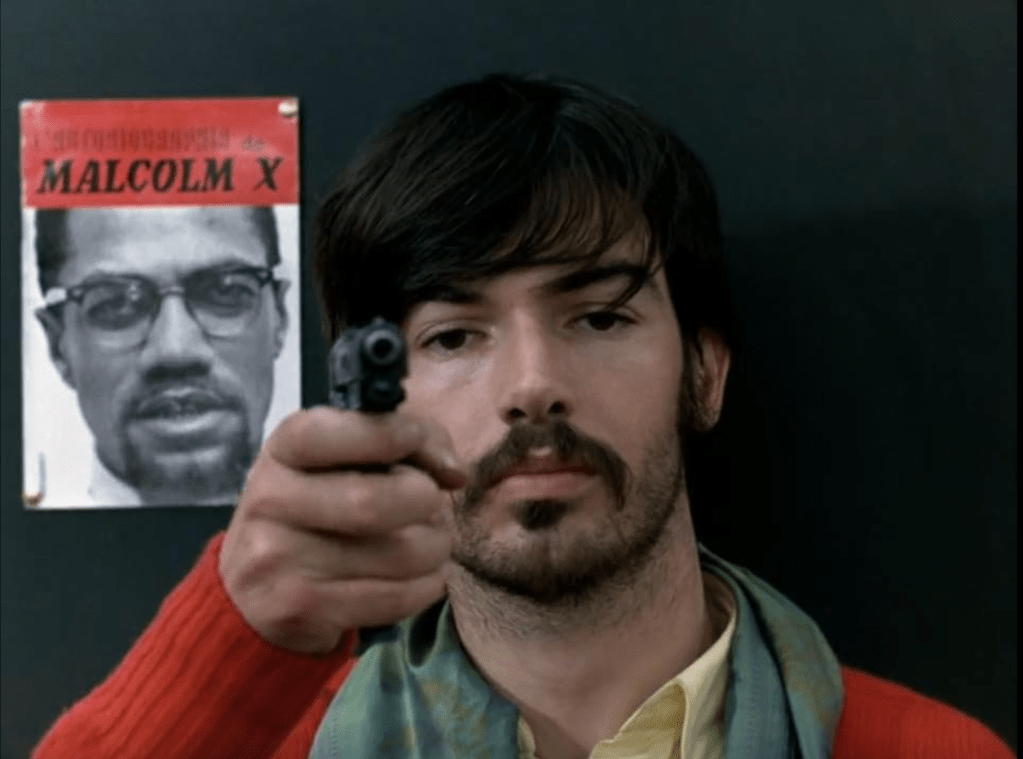

Cut. A woman in a conical hat surrounded by a stack of red books; to be precise, the book “Words of Chairman Mao Tse-Tung” wrapped in red ribbon, multiple, one above the other, side by side. The book as the new masonry brick. And locked inside, a bloodied young woman wearing a traditional Vietnamese cone hat. She calls out to us. She calls out, “The Viet Cong will win.” Once. Twice. Then she is handed a rifle. A toy rifle. She unfolds it and shoots through the stack of books at the invisible enemy behind the camera. At the enemy behind the camera. She folds up the rifle. Folded up, it’s a radio. She follows the horror news announced from the radio. Cut.

The young woman’s name is Yvonne and she lives in a shared flat with four others. The others are intellectuals from middle-class families. Yvonne is a peasant girl, a part-time prostitute and in this flat-sharing community something like a maid, who is allowed to participate in the game of the big ones only just enough to get close to victory but never to emerge as the winner.

She and the four others are united by the idea of a socialist world revolution. Whereas they share the thought, it also shares their views on how the socialist revolution should take place and how the socialist society should live. The Maoists of the group want a revolution by force; the Marxist-Leninist relies on peaceful co-existence, the nihilistic anarchist keeps quiet and waits for the day when he is allowed to pull out the gun. Or not. It’s all nothing anyway. And Yvonne, the proletarian? I don’t think she understands.

In this shared flat, with the camera as a visitor, we get to know these young people. Full of ideals and ideologies. In long mutual speeches, razor-sharp word volleys are thrown around the ears. The walls are decorated with further proclamations. Poets and thinkers are erased on blackboards. Plays are performed. Literary texts are read out over bourgeois coffee and ignored by the listener. Interviews are given. Assassinations are rehearsed with bows and arrows. The socialist agenda is predominantly recited among the Residential community in front of each other. Like a lecture. Eat the spoken word to shut up. Hardly any discussion or discourse takes place among the participants. Any dissent is punished by expulsion from the group. Trench warfare under the same guise. The Popular Front of Judea versus the Judean Popular Front.

In the colorful film “La Chinoise,” Godard stages the various socialist voices through satirical, absurdist collages. Above all, however, he stages the unworldliness of the intellectuals who, in over-thinking and over-philosophizing, have inflated an ideological filter bubble consisting of a lot of hot air; who always think they are holding up the proletariat, but are as far away from the proletariat as they can get and instead integrate the only proletarian only for what she is useful for: cleaning and groping.

Thus, the film is not per se against socialist movements. Nor does it portray the characters ridiculously. It only caricatures the overambitious zealotry of some left-wing students or intellectuals, who talk a lot of smart-sounding stuff to cover up their own duplicity. Rather, it picks up on the rebellious, anti-capitalist zeitgeist of the time and exaggerates it into an ideological hall of mirrors in which the characters get lost. This is still exciting today, when the problem of filter bubbles can also be found all too often in the current world.

In any case, I laughed a lot at this film, marveled in fascination, shook my head and slapped myself on the knuckles more than once.

Conclusion

A film for all those who say “I am against it, because you are for it”.

Facts

Original Title

Length

Director

Cast

La chinoise

95 Min

Jean-Luc Godard

Anne Wiazemsky as Véronique

Jean-Pierre Léaud as Guillaume

Juliet Berto as Yvonne

Michel Semeniako as Henri

Lex De Bruijn as Kirilov

Omar Diop as Omar

Francis Jeanson as Francis

Blandine Jeanson as Blandine

What is Stranger’s Gaze?

The Stranger’s Gaze is a literary fever dream that is sensualized through various media — primarily cinema, which I hold in high esteem. Based on the distinctions between male and female gaze, the focus is shifted through a crack in a destroyed lens, in the hope of obtaining an unaccustomed, a strange gaze.

-

Cléo from 5 to 7 .. or Reflections about live up to 11

What is it about?

A city-famous, carefree singer has to wait two hours for her diagnosis. During the two hours, she goes through an odyssey in Paris, during which she reflects for the first time on life and death and on being human.

What is it really about?

In Sartre’s “No Exit” three characters gather in a locked room from which they have never emerged and are completely alone with themselves. As it soon turns out, the closed room is the dungeon in which sinners are locked up for punishment after they have died and are there at the mercy of eternity forever. The endless waiting in this atemporal room, the sheer endless waiting for redemption, is an aspect of Sarte’s hell, far removed from the sadistic, fiery shock imagery of a Hiernoymus Bosch.

The waiting forces the gaze inward. There is no escape, only the pushing of an uncontrollable force into one’s own deepest levels of consciousness. Waiting eats up the mind, swallowing the existential core and digesting it over and over again until one vomits and heralds the re-consumption followed by re-digestion one more time.

This is what happens to the titular Cléo: the famous singer has to wait for two hours after a medical examination to learn her diagnosis. A wait for the redeeming answer: healthy or sick after all? We are allowed to accompany her handling of these waiting hours – almost in real time and divided into chapters – in an impressive way: The hoped-for premature finding of an answer with a tarot card reader; the search for a distraction with the hasty purchase of hats; the search for the comforting visit of the lover; the search for hope in music. But what cannot be found can perhaps be found through a way out: escape from familiar surroundings, from what constitutes current life; escape into the unknown, among people one does not know; escape to a good friend; escape to the movies; escape to nature, the place of last, lost souls; and finally, escape from waiting, fear, and worry. The escape as a way out, to finally look for oneself.

Cléo, who is a successful and carefree singer, is forced by the waiting to see herself for the first time. At first, she seeks support in the mirror; gazes into her healthy and beautiful exterior, caresses and comforts herself with beauty; enjoys when pedestrians’ gazes fall upon her. She seems to exist only when she is marveled at and comforted; seems to be subject only then. But this consolation almost does not work; her always objectified role of the beautiful, the longing and the musical shatters her self, her perception as self, her courage and her vitality. For the first time she becomes aware, beneath the supple surface of her skin, that there is something else lurking within her. And so the escape from the theater becomes a touching search for the subjective, the existential self. For this, Cléo must shed her masquerade, shed everything she is known and famous for; for this, she must endure the infernal stares of people who relentlessly look at her and devour her because she is not what she seems. Cléo must endure this until she reaches where mercy awaits her and what she is really looking for: herself.

Cléo, short for Cleopatra, is – as we learn later – not her civil name at all. It is the name she is given. She – the royal one or she – who is made queen – is actually called Florence – the blooming one. And she also blossoms in a park from her withered existence when, near a waterfall, she meets the young soldier Antoine, who is also enjoying what may be his last existence in this kingdom of nature before he leaves for the Algerian civil war. With him as her interlocutor, she soon finds herself a mirrored soul. In this final and longest chapter, the wait becomes a bit more bearable, fulfilling, and healing. The emotional strength of this chapter is indescribable. Rarely have I seen such a wonderful portrayal between two perfect strangers who can discover so much hope and lightness in their constricted existence. The discovery of the present, of existence, of existence in this very second and the fading out of the closed past (fame, masquerade) and the open future (healthy or sick), because both don’t matter in that moment.

And the consciousness carries when it realizes that the space of life seems only closed and that one is not forced to wait endlessly or to surrender oneself in the mass. And even if it sounds like a spoiler (but it is not): It’s the most beautiful happy ending that isn’t a happy ending.

P.S.: Godard and the enchanting Anna Karina get to experience what it means to see the world in black or white in a little short film in the movie.

P.P.S.: I can imagine that Richard Linklater got the idea for Before Sunrise from this film.

Conclusion

A film I would watch even if I only had two hours to live.

Facts

Original Title

Length

Director

Cast

Cléo de 5 à 7

90 Min

Agnas Varda

Corinne Marchand as Florence ‘Cléo’ Victoire

Antoine Bourseiller as Antoine

Dominique Davray as Angèle

Dorothée Blanck as Dorothée

Michel Legrand as Bob, le pianiste

Jean-Luc Godard as L’homme aux lunettes noires…

Anna Karina as Anna, la fiancée blonde…

What is Stranger’s Gaze?

The Stranger’s Gaze is a literary fever dream that is sensualized through various media — primarily cinema, which I hold in high esteem. Based on the distinctions between male and female gaze, the focus is shifted through a crack in a destroyed lens, in the hope of obtaining an unaccustomed, a strange gaze.

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.