-

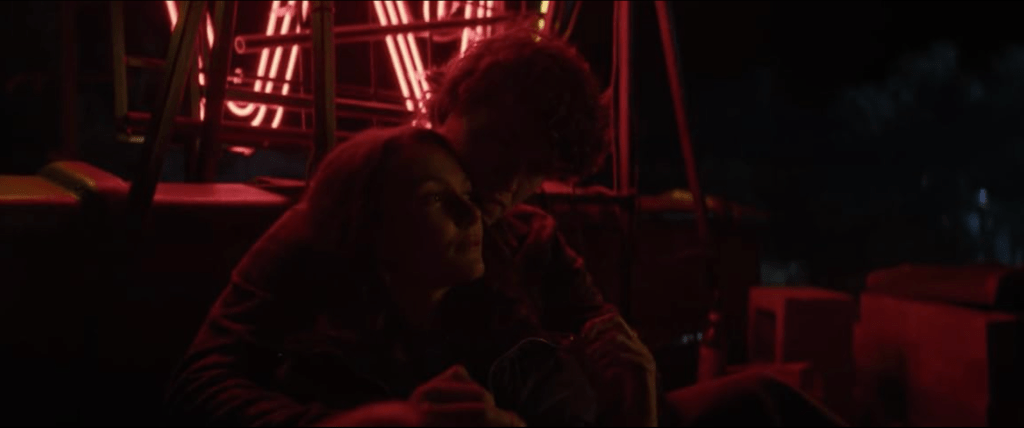

I Saw The TV Glow .. or: The Transition of Being.

What is it about?

A TV series reveals more about a boy’s identity than he can bear.

What is it really about?

Oops, it’s not just the TV that’s glowing. Your eyes are glowing too. Your nerves are glowing. Something is glowing that dazzles and offers a coziness in the blinding light that is all too easy to snuggle into while slowly going crazy.

The body before the glow

The weekend morning program on TV in the 90s enveloped my childhood bedroom in an amorphous meadow in which I rolled around week after week. The blades of grass of the flickering red, yellow and blue pixels of my tube TV oscillated around me so that I was completely immersed in it. In addition to cartoon series such as The Simpsons, Ren & Stimpy, Rocko’s Modern Life, Hey Arnold, Aaaahh Monsters!, I was telemedially socialized by series such as Pete & Pete, Parker Lewis, Goosebumps, Kablaaam!, The Dinos and Clarissa Explains It All. This often very anarchistic, colorful excessiveness of the morning program was supplemented in the evenings by the vampiresque adventures of the series Buffy or the terribly strange horror stories of Mulder and Scully in The X-Files, as well as the curious journeys to the Outer Limits or the relaunched Twilight Zones.The commercial breaks between shows were never skipped, but lit up my poster-covered nursery as frenetic overtures thanks to their memorable jingles and super-awesome toy endorsements. Back then, when I was 1.20 m tall, only jumped around in XXL shirts, wore shoulder-length hair and chipped my front tooth while skateboarding, when I wasn’t playing basketball like Michael Jordan or Denis Roman or shooting friends with red turtle shells in Super Mario Kart. But time and time again, my boyish flesh sat hallucinating in front of the flicker box and let the colorful rush of images drive me out of reality day after day.

The glow

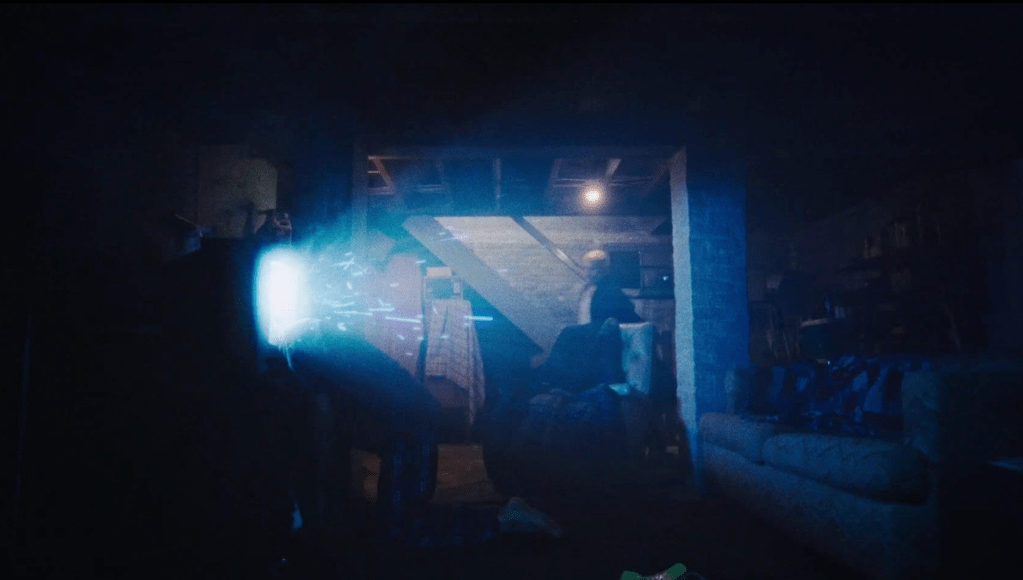

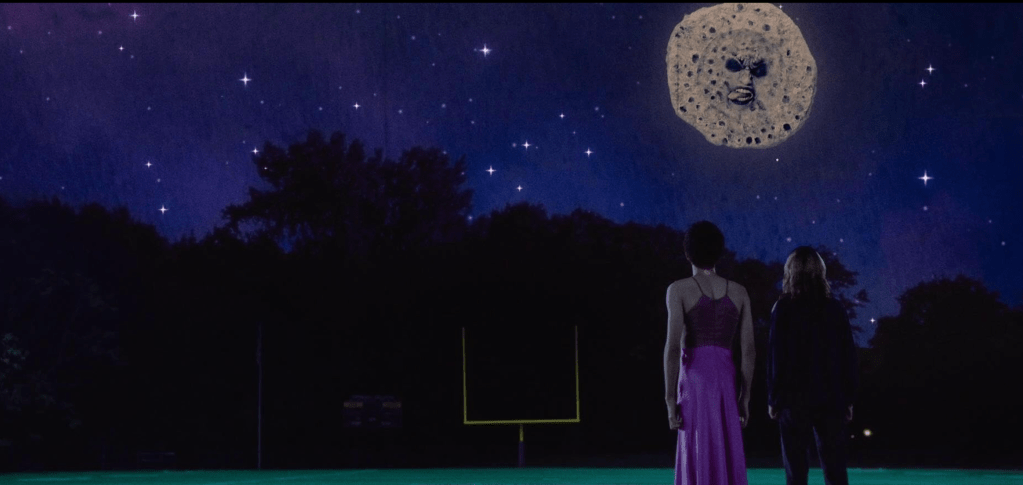

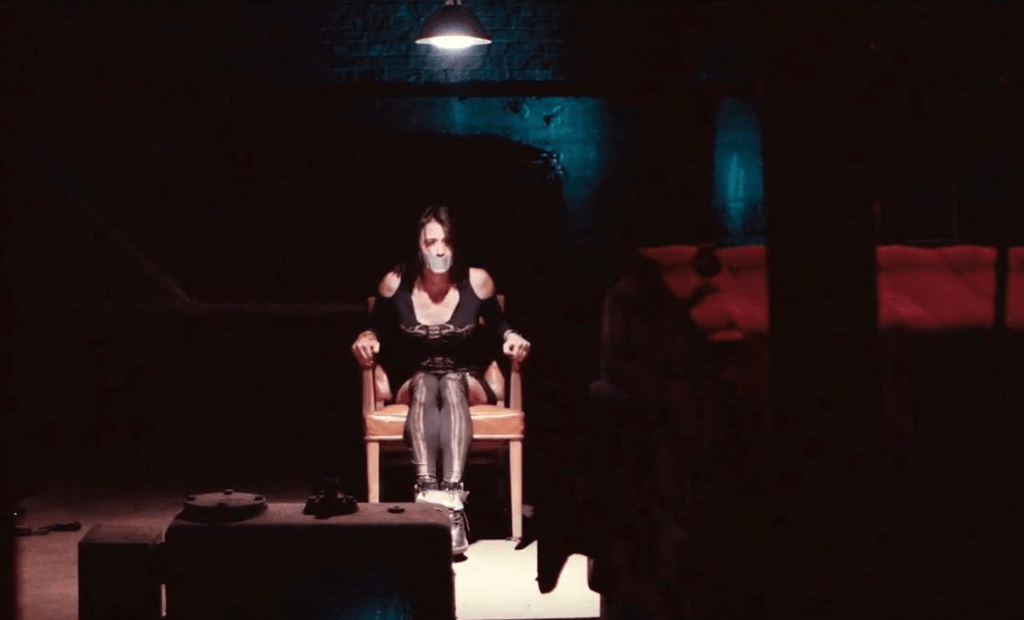

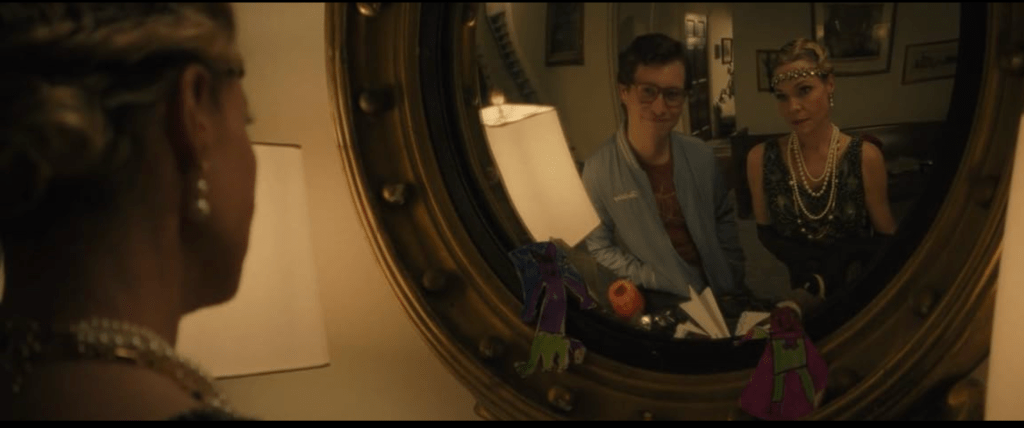

I Saw The TV Glow throws us as viewers right into that time. A time when it was essential not to miss an episode of your favorite series because there was simply no opportunity (or prospect) of ever being able to watch it again. The pre-pubescent Owen loses himself with an older classmate in the teen series called “The Pink Opague”. The series is about two teenage girls telepathically interacting with each other to fight the monsters sent to them week after week by the chief villain Mr. Melancholy. Owen and Maddie watch the series for five seasons (although Owen only watches it in secret because his parents forbid him to do so). Then, surprisingly, the show is canceled with a tragic ending in which Mr. Melancholy wins over the girls, rips out their hearts and leaves them to die in the Midnight Realm. When the series finale airs, Maddie also disappears, leaving behind only a burnt-out television and Owen, who does not want to flee the small town with her.Many years later, Maddie unexpectedly reappears in Owen’s dreary and miserable life and tells him about her turbulent life, culminating in her having herself buried alive so that she can live in the world of “The Pink Opague”, where she lives on as one of the protagonists in a sixth season. By telling her life story, she reveals more to the inhibited and intimidated Owen than he wants to know about himself. She questions his connection to reality and whether he really remembers the film evenings together as accurately as they took place or whether he has not rather internalized them as a fictionalized memory narrative about the series “The Pink Opague” as a projection screen. Images of him in a woman’s dress in the style of the TV show are faded in at the moment of the confrontation, further images of him merging with the female main character of the series. Maddie offers him the opportunity to say goodbye to this world, which he interprets as reality, and to destroy his ego from this illusory reality in order to finally reincarnate in the real world, namely that of the “The Pink Opaque”.

Owen himself is presented throughout the film as a withdrawn and introverted person. His aura is entirely taken up by poetry-less melancholy and grave-voiced apathy; there is never an emotional movement to be discovered in his facial expressions, apart from a bashful twitching of the corner of his mouth when he wears the dress. His sexuality remains ambiguous, if not non-existent, for large parts of the film. When asked whether he likes women or men, he replies indecisively with “I like series”. In this central, harrowing re-encounter with Maddie, the central conflict within him is revealed: Just as Maddie could not find her way in the heteronormative world and even fled from it, Owen, however, is still stuck in this repressive world for his nature, in which he continues to find himself uncomfortable in his boyish body. She tries to convince him to leave this imposed, dysfunctional world, to bury his old, masculine self in order to live on as the person he had projected through the series “The Pink Opague”, namely in the main female character Isabel.

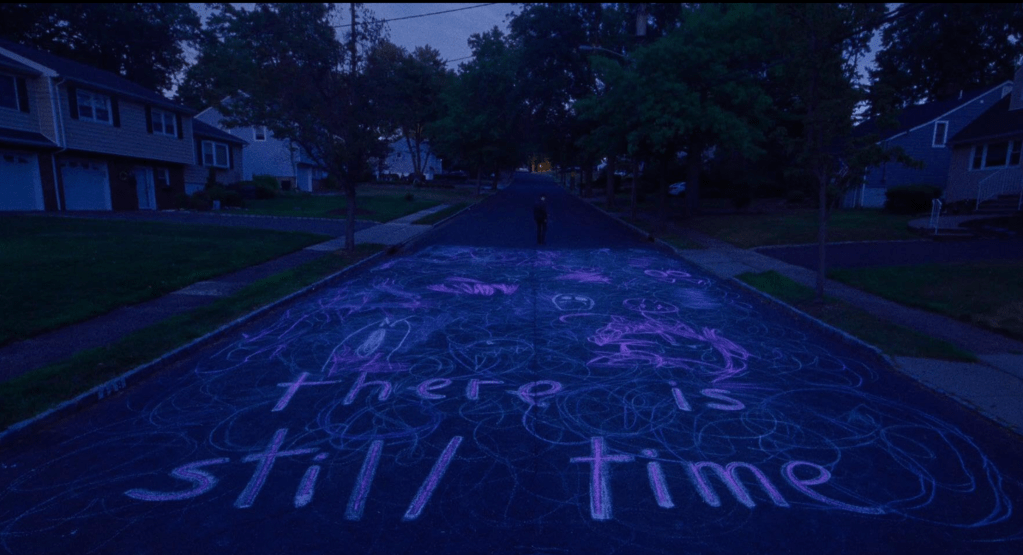

The glow of television (and The Pink Opague in particular) thus represented a portal to self-discovery for Owen in childhood and became an oppressive force as he grew older, reflecting his retreat into repression and social conformity. In the midst of this incandescence – in this escapist shelter – lies Owen’s true identity, dwelling in electronic flashes between transistors and line transformers that constantly reveal the spark of potential to reclaim his identity (“There Is Still Time”).

The body without glow

The rough summary already makes it clear that I Saw The TV Glow is not an easy movie to enjoy on a Sunday afternoon. I Saw The TV Glow demands a lot from the viewer, both thematically and in terms of staging, even if it occasionally tickles the viewer with belly-brushing nostalgia. Not only is the film clogged with multi-layered symbols that need to be deciphered, it is also shrouded in a gloomy fog of melancholy and depression, a twilight, ghostly state that is complemented by a washed-out image and camp 90s VHS aesthetic. Despite minor nostalgic Buffy reminiscences, there’s no sunshine and candy here, but pure human suffering. The intense scenes drip with soul-baring, melancholy suffering full of existential problems, domestic violence and social repression, in which the (symbolic) death of the self ultimately feels more like redemption.To make matters worse, however, the formalistic orientation of the film shows figures but no characters. Throughout the entire running time, the characters’ personalities are never fully explained to the regular viewer; in their ambivalent, elliptical portrayal, they are more like figurative blueprints into which the viewer can empathize and sympathize with the characters’ emotional states and situations. Provided, however, that they can. Otherwise, the figures are not completed characters, but inadequately projected shells.

Through the personal past of non-binary transperson Jane Schoenbrun (director and screenwriter), the discovery of gender identity is treated allegorically through the characters of Owen and Maddie, but – wisely – without spelling it out with hammer-smashing clarity. Instead, Schoenbrun sends us through a neon-drenched dream environment in which dark reality and even more monstrous fiction blur for us, just as the construct of binary gender loses its distinguishable edges, falls apart in cracks and is transformed into a dense fluid.

Since I didn’t question my gender identity in puberty (or had to question it out of an inner feeling), my biggest problem is definitely, unfortunately, not being able to find any personal points of connection to the schematic characters in order to fully empathize with their conflicts; it would probably be different if they were defined characters I could empathize with. In I Saw The TV Glow, therefore, I have to watch two characters that I can relate to but rarely empathize with (and in particular Justice Smith as Owen, whose wooden, flat acting repeatedly knocked me out of immersion). As a result, I can enjoy the movie intellectually but not emotionally to its fullest. The consistently depressing moods are difficult for me to grasp; especially in the episode when Maddie returns, should have found herself, but still seems miserably depressed. However, I was overwhelmed with enthusiasm in every scene of “The Pink Opague”; especially the staging of the terrifyingly dark, haunting series finale.

The body in a disembodied glow

I deeply regret the fact that I was denied access, because the film has incredible potential that will keep many generations busy exploring. In any case, through Reddit and Letterboxd, I have the feeling that younger Gen Z in particular have a more natural approach to the movie. Perhaps it has something to do with the fact that I grew up in a different environment in terms of identification through the presentation of the body and physical representation of identity in the age of the internet. As a young adolescent in the early 2000s, the question of gender identity was hardly ever asked in public. Of course, heterosexuality, homosexuality, bisexuality and transsexuality were accepted in my environment (while the fashionable term of metrosexuality was added in the media), but the discrepancy between biological and social sex (gender) was not discussed in public or even at school.The fact that the Internet will enable a broader perspective here is exciting because in the worst 56k modem times I remember the Internet as a haven of disembodied voices that communicated with each other worldwide in letters and smileys. You were what you wrote, detached from your body or biological gender, religion, age, everything. With the popularization of social networks (especially MySpace and even more so Facebook) and the publication of images, the body image automatically came to the fore, while the written word, the disembodied voice, faded away. Increasingly, the Internet, which was in itself disembodied, turned into a stage for representative body images, which were increasingly concerned with questions such as “What do I want to show of myself?”, “How do I want to be seen by others?” and “What do I look like in this photo?” in order to participate in socio-collective events. The infinite and invisible eyes on the internet immediately prioritized the body over the voice (as a representative of the soul). As a result, the body became overly important.

Apps such as Tinder reinforced this hyperbolic importance of the body, with only the effect of the body determining the sexual offer. It has probably also changed the way we look at ourselves, because the hyperbolic importance of the body has confronted us with our own bodies more than ever before. In such a setting, we struggle more than ever for autonomy over our bodies. But in its repressive, simple nature, society has an idealistic view of and civilizational expectations of the body. An individual body that deviates from these expectations is at risk of being condemned (even on the internet itself). To make matters worse, the body always goes hand in hand with sexuality, as it attracts and dominates the first glance of desire and reciprocally also makes it clear to us that the shape and form of our own body also regulates access to sex, i.e. enables or even blocks it. However, the increased confrontation with one’s own body that accompanies this also allows it to be experienced more consciously.

Where there is a threat that the flood of images will not only preserve heteronormative gender images, but also infinitely reproduce and ultimately perpetuate them, the spectrum outside the norm can also assert itself and show itself. Through the international, language-barrier-free staging of bodies, it is thus also possible to find one’s buried gender identity in solidarity amidst the colourful array of bodies. Non-binary and trans identities have thus (finally) become more visible and can increasingly be recognized as legitimate forms of expression of individual identity. While such identities were marginalized to the point of complete invisibility and suppression in my youth, they are now experiencing more social (albeit insufficient) acceptance thanks to Gen Z, which grew up with a focus on the physical as a matter of course early on in its heyday. And even if this is still a difficult path for those affected, it is a social enrichment for which I Saw The TV Glow makes an intelligent and creative contribution – even if I find it difficult to access.

Conclusion

Good.

Facts

Original Title

Length

Director

Cast

I Saw The TV Glow

100 Min

Jane Schoenbrun

Justice Smith as Owen

Brigette Lundy-Paine as Maddy

Ian Foreman as Young Owen

Helena Howard as Isabel

Lindsey Jordan as Tara

Danielle Deadwyler as Brenda

Fred Durst as Frank

Conner O’Malley as Dave

Emma Portner as Mr. Melancholy…

Madaline Riley as Polo

Amber Benson as Johnny Link’s Mom

What is Stranger’s Gaze?

The Stranger’s Gaze is a literary fever dream that is sensualized through various media — primarily cinema, which I hold in high esteem. Based on the distinctions between male and female gaze, the focus is shifted through a crack in a destroyed lens, in the hope of obtaining an unaccustomed, a strange gaze.

-

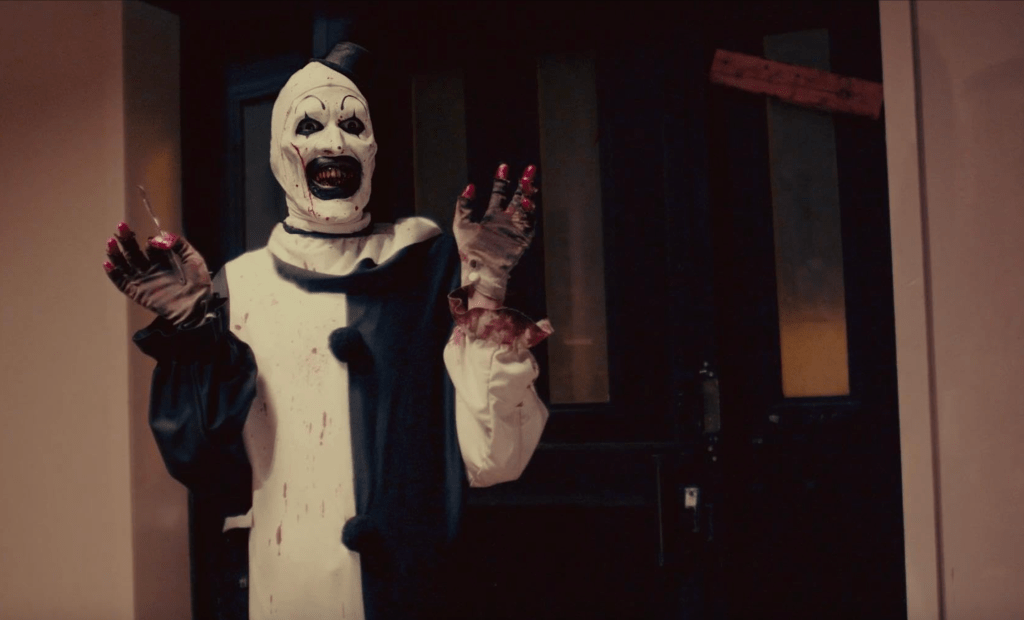

Terrifier .. or: What terrifies us the most is the shadow of ourselves. Or a clown.

What is it about?

A clown – a shadow of ourselves – lives out his sadistic streak to the full on Halloween night.

What is it really about?

I’m late for the party again. But what counts: It happened. I didn’t actually want to. I surrendered. I was watching Terrifier. I feared the worst. I liked it surprisingly well.

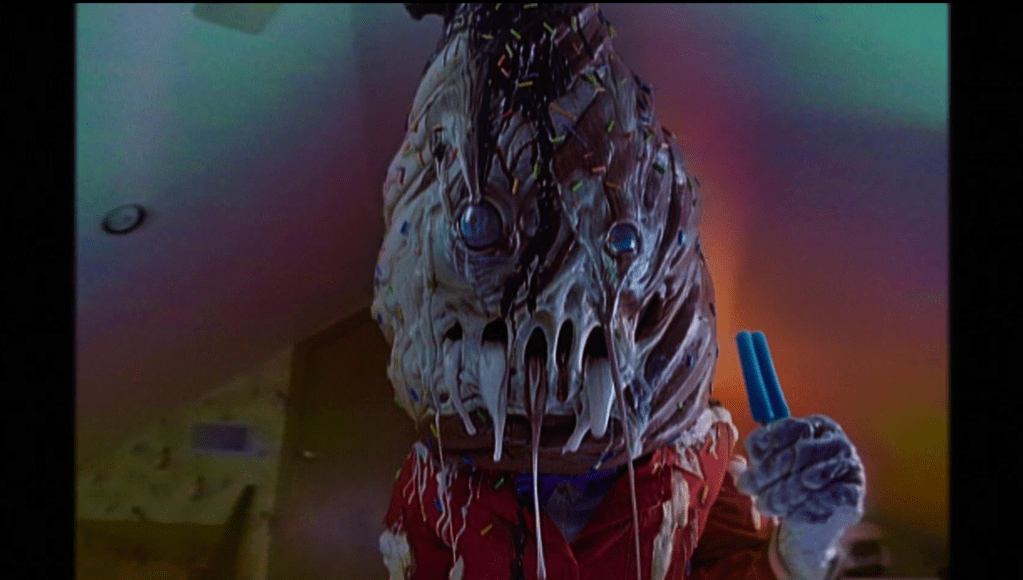

The violence-laden mythos dripping from Terrifier’s reception wrapped itself around my nerves and squeezed out splatter joy. But not only me. With the third orgy of blood, Art the Clown makes his way through the drooling crowds. A murderous clown, then. Hasn’t that been done a hundred times before? Pennywise. The killer clowns from the farthest corner of space. Yes, even the Joker somewhere. Or the cinematographic curiosities of the Insane Clown Posse. So why is Terrifier such a huge success? You don’t have to look at the movie too closely to see the secret recipe (which was certainly put together unconsciously): The excess of the clown portrayal, driven to perfectionism, as well as the boundless excess of splatter. And – let’s not forget – the horror clown panic that scared the bejesus out of innocent home-goers in 2016.

Clowns per se are already predestined to be scary. The clownish mask, along with suggestively presented humor and joy, hides the true face and thus the true self. We do not see the personality, but the persona. A mask that only shows us what we are supposed to see and hides what we are not supposed to see. The true facial expressions of the clowns are never fully legible beneath the make-up and/or mask, and are also reinforced by their silence and covered up with expansive and theatrical gesticulation. Their voluminous red lips look as if they are still covered in the blood of the victims they have torn or as if – due to the emphasis on the lips – they are about to be kissed by a stranger. The blood-red knobbly nose pops out of the pale face like an unnatural deformation. The parabolically drawn eyebrow lines intonate beams of joy and curiosity, but in their rigid sameness mask any absence of negatively connoted but highly human emotions such as doubt and irascibility. True to Mark Fisher, everything about them seems strange, an unnatural modification of humanity that is only accepted because we have been socialized to perceive clowns as harmless klutzes rather than bizarrely costumed adults behaving in an ambiguous travesty of childishness.

Next to them are the aesthetically and elegantly native Harlequins. These color-desaturated clowns with black and white chessboard costumes not only play joyful emotions in pantomime performances, but also the opposite, lateral keyboard of emotions: Namely sadness. They also like to use make-up accents such as the popular tear under one eye. This makes them not only magicians of laughter, but also proclaimers of guilt, as the audience in particular likes to be charged with complicity in the actor’s sadness and forced into action so that the Harlequin’s tears can return to the euphoria-inducing opposite pole. The muteness of the clowns and harlequins in particular requires us to interpret the gestures and mimes instead of reading them. Since every gesture and facial expression is also pure manipulation, expressed solely in order to deliberately demand a reaction from us (by laughing or feeling sorry for the clown), an unparalleled threat lurks unconsciously beneath the make-up, which is further intensified when we become aware that a clown (or harlequin) is blatantly chumming up to us. We are exposed to them and either we laugh along with them or God have mercy on us. Because this ingratiation is bound to an egotistical purpose. But what do these clowns want from us? Is it really just to make us laugh, or are there much more vile thoughts lurking behind these masked countenances, but they never become tangible or perceptible to us because their holistic appearance is permeated by lies and nothing but lies. This is exactly where we come to Terrifier or Art der Clown.

Clowns (like Art) also represent an archetypal embodiment of the trickster, whose chaotic, infantile and often ambivalent habitus violates general rules and social norms and resolves this with ironic and surprising actions. C. G. Jung writes: “The trickster is a figure that emerges from the primitive background of the collective unconscious. He is a fighter, a seducer and a cunning deceiver.” The clown as trickster can therefore be assigned to the shadow archetype, a dark side of the self described by Jung. The shadow stands for suppressed and unconscious parts of the personality, which often contain morally reprehensible or socially unacceptable characteristics. Clowns, as figures who flout the rules and act in crazy ways, often embody precisely this shadow of the collective unconscious. The shadow here is the negative of the persona, i.e. the mask that he himself displays and which stands for our own normative masks that we put on every day and which – according to C. G. Jung – helps us as “individuals to present ourselves in the world, but which often has little to do with the inner self”. As a result, the shadow of the clown, his charged urge to create chaos, mirrors the unconsciously lurking urge within ourselves.

Art the Clown embodies the art of being a clown like no other. In a five-minute scene at the beginning of the film (which unfortunately receives far too little attention), his monstrous strangeness and thus the monstrous strangeness of clowns themselves is staged in the most uncomfortable way possible: He strides into a pizza store, his heavy garbage bag slung over his shoulder. His gaze is fixed on the main character, Tara, as if he could look directly through her eyes into her body of flesh. He sits down at the table next to her and continues his creepy stare, ignoring everyone around him as if they were just smoke and mirrors, until he finally loosens his predatory fixation and beams up to both ears. But his clownish, joyful smile remains fixed on Tara like an awkward man who doesn’t know how to approach the object of his desire. Tara, however, is at the mercy of his intrusive gaze, because while he is masked, she is unmasked. Compared to him as a clown, every emotion can be read from her facial expressions and gestures. She feels completely naked in his superior presence, flayed to the flesh, her vulnerability already torn from her throat and exposed. When he slips a ring from the gumball machine over her finger, her fate is determined. She is at his mercy until death do them part. This demonic creature will not allow a divorce. Because he appears threatening throughout this scene, although he does not directly threaten anyone, but – on the contrary – rather suggests attention and joy and even love, it becomes clear to us that this will not have a good ending (or a good slasher ending).

Behind Art’s shadow, a grotesque fantasy of violence manifests itself in unbelievably perverted destructiveness. The brutality with which Art massacres his victims is not entirely new or particularly cruel for the slasher genre. The main reason for the brutality here is, on the one hand, the astonishingly neat effects and, on the other, the lechery with which these are indulged to satisfy a lust for the spectator, who delights above all in the prolonged, particularly torturous execution of women with unparalleled sadism: one woman is hung upside down naked with her legs spread apart and sawn up by hand from the vagina to the head. Another woman’s breasts are cut off, which Art then puts on like a brassiere. Before that, he tortures her by keeping her “child” (a doll that the woman thinks is her child) with him and thus maltreating her worried motherly feelings. He eats off another woman’s face until the beautiful woman is left with a disfigured grimace.

Art is also deadly towards men, but not with the same joy of killing as he is towards women. He only kills Tara – the object of his original joy – with a rather emotionless shot to the head, and even though he empties an entire magazine in her face afterwards, it seems less lustful than with the other women, but rather personally hurt and resigned to her rejection. Since the violence against women primarily amounts to the mutilation of sexual characteristics, this is remarkable because Art otherwise shows no sexual desire towards the women, but only the destruction of those sexual characteristics themselves. As he acts in a highly infantile, prepubertal manner, this sexual desire cannot blossom directly as Eros, but can only lead to Thanatos, the death instinct. By merging the sexuality of his victims with death in the brutalities, Art presents the female body as an object for the embodiment of evil and violence itself, whereby the female body becomes the stage on which the destructive side of sexuality unfolds. By mutilating women’s bodies in a drastic manner, Art attempts to gain control and power over the feminine, because he has no other option over his childishly functioning (i.e. impotent) male figure.

With the drastically transgressive performance of Art der Clowns and its diegetic function of representing both the persona and the shadow of the collective unconscious, the audience achieves a catharsis together with their ambivalence of their own persona and shadow. Young women re-experience being at the mercy of these sadistic male gestures, just as men believe they have regained both the superiority and impotence of their patriarchy. Animus can remain animus; anima remains anima. Together they wander through an opaque vaulted cellar littered with remnants of days gone by, whose labyrinthine topology resembles not only the unconscious, but the marital wandering of life itself.

Conclusion

Better than expected. But not art at all.

Facts

Original Title

Length

Director

Cast

Terrifier

84 Min

Damien Leone

Jenna Kanell as Tara

Samantha Scaffidi as Victoria

David Howard Thornton as Art the Clown

Catherine Corcoran as Dawn

Pooya Mohseni as Cat Lady

Matt McAllister as Mike the Exterminator

Katie Maguire as Monica Brown

What is Stranger’s Gaze?

The Stranger’s Gaze is a literary fever dream that is sensualized through various media — primarily cinema, which I hold in high esteem. Based on the distinctions between male and female gaze, the focus is shifted through a crack in a destroyed lens, in the hope of obtaining an unaccustomed, a strange gaze.

art, cinema, clown, clowns, culture, essay, film critic, film review, movie critic, oscar, Review, splatter -

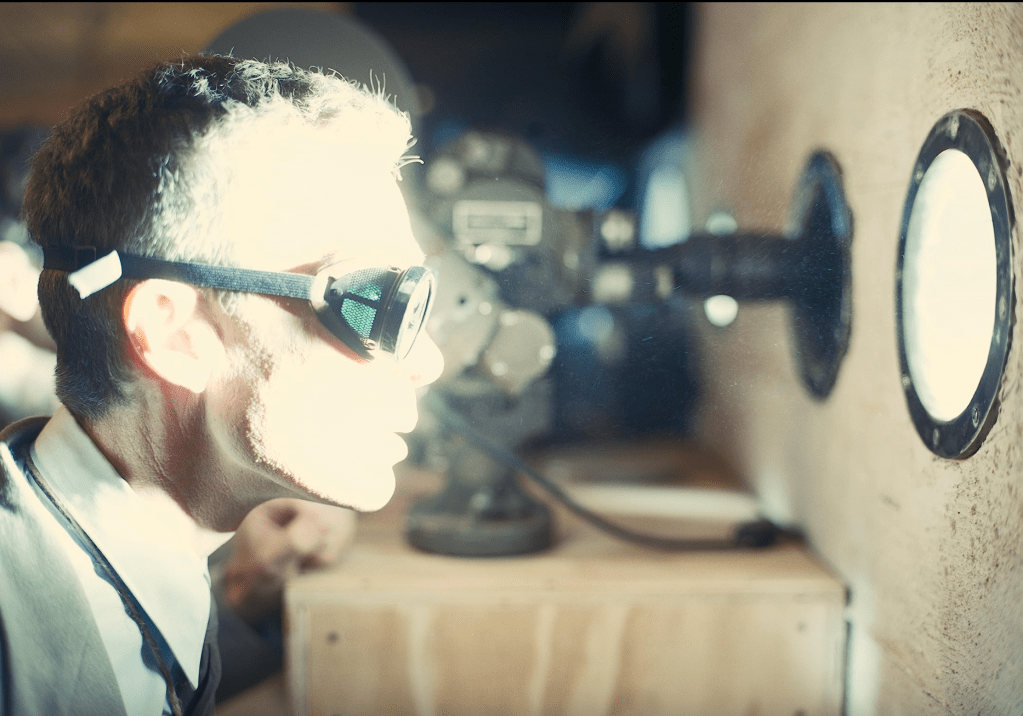

Oppenheimer .. or: Nolan’s Cold-Hearted Masterpiece and Its Emotional Void

What is it about?

A scientist is hired by the US government to produce the atomic bomb. The victory march against the Nazis is to be realized. After the Nazis are defeated, however, there is a new enemy: the communists. Unfortunately, the scientist has a past that the government considers too communist.

What is it really about?

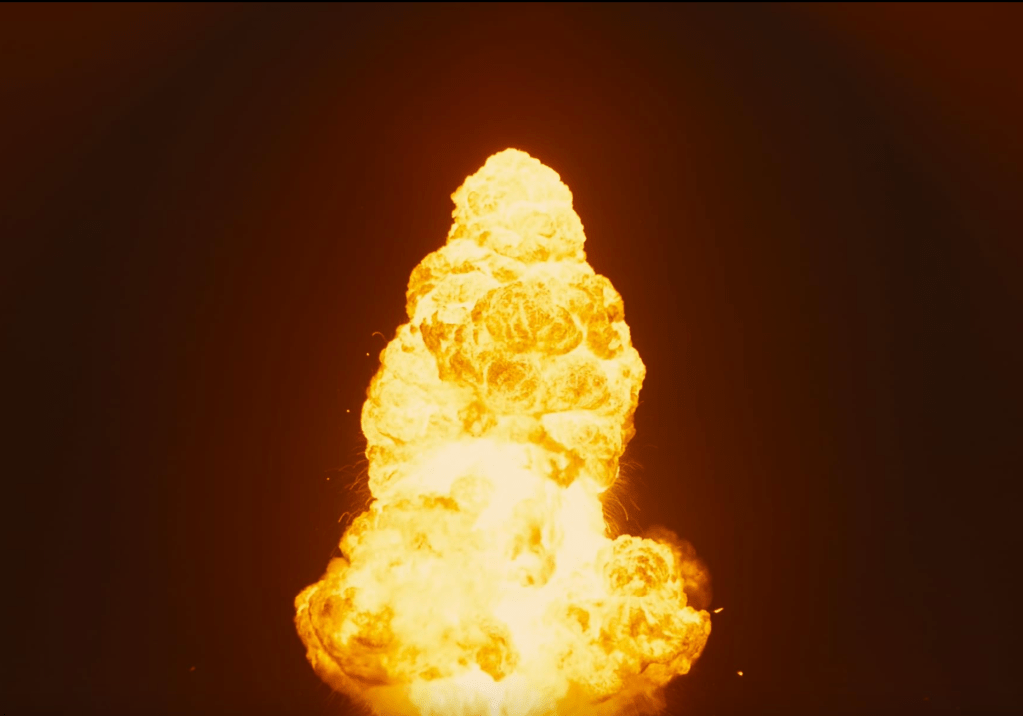

Nolan makes movies. His narrative style is modern, highly industrial, effective. A fusion of pulverized and liquid ideas into a massive, chunky unit, which is compressed in a repeatedly rhythmic pressing hammer until a technically clean, almost flawless work emerges, which, during the quality check, elicits great amazement and murmurs from the engineers with its monolithic creative power; and finally, with the unanimous nod of approval, “Bombastic!”.

Oppenheimer is thus a technically flawless product from Nolan’s creative factory, in which not only Oppenheimer’s private and professional life is told, the research and production of the atomic bomb, the arms race of the USA against the Soviet Union, the political and arbitrary witch hunts for communists on the part of the USA, to which Oppenheimer is soon added; forgetting what he had done for the USA by building bombs, while his own uncritical past – on the fringes of communist-motivated acquaintances and family – will never be forgotten. All the ideas and aspects of Oppenheimer as a person and his dramatic career, as well as the reception of his person and his work, are calculatedly embedded in a story of intrigue against him, which gradually comes to light.

Nolan makes extremely effective use of cinematic narrative techniques in a well-considered and measured manner in order to deal with this mass of content in an exciting way. Thanks to the galloping, timeless editing, the viscerally vibrating sound, the powerful acting, the intimate but also epochal, grand images, a light-footed colossus is created over the enormous running time of three hours, which never, really never, bores at any time. Even with my initial sleepy eyelashes, the movie woke me up from any longing for sleep.

But as apparently perfect as this monolith appears, as a rapturous masterpiece that the world has never seen before, Nolan would not be Nolan if he did not make the same mistakes he has always made – at the latest with the departure of his brother as co-writer: It’s a cold movie by a cold-hearted director. Nolan is an undercooled perfectionist who, in the zeal of his filmmaking, wants to raise storytelling to a new level, and it is this ambition that enables him to capture such narratively flawless films as Oppenheimer on celluloid. His recurring fascinating visions in the eternal duel with the human companion called “time” are, as in Oppenheimer, charming and gripping, told with maximum concentration. But the heart is repeatedly missing.

This makes him very close to Stanley Kubrick, whom I consider to be an equally perfectionist, conceptual person who designed his films on a chessboard or a formula board instead of letting it happen intuitively, like David Lynch, for example. But Kubrick seemed to be aware of the flaw that he didn’t have a knack for emotional characters and thus emotional films; either because he didn’t have the flair or the interest. This is why his characters are predominantly cold-hearted, cynical, violent or perverse; mostly driven by their primal, mostly negatively connoted fantasies. Kubrick’s characters are therefore never shining heroes, but always losers or heroes for whom one would never wish a victory.

But Nolan always tries to tell stories about radiant heroes who often suffer inwardly and who have to fight against the injustice of the world towards them. But by no means does he manage to convey emotion believably because his only tricks of the trade never go beyond pathos and kitsch; be it the awful “love is a force of nature” monologue in Interstellar, the two-sentence rumbling relationship dynamic in Inception or the horribly hackneyed, unspeakably portrayed love story in Tenet. His superficial, purely functional characters act less out of themselves than because the story demands it of them. These characters have no secrets, no passion, no inner life. They only ever present concepts. If the characters are supposed to be sad, then they should cry. If they are supposed to love, then they should kiss. If the characters are supposed to be angry, then they should break something. The production remains superficial, with clichés, with the perspective of an autistic person discussing how fellow human beings express their feelings.

Oppenheimer is no exception. We learn almost nothing about Oppenheimer the man, his ambitions, his inner turmoil, the perspective of his inner life and the denouncing world around him, the strange relationships with women. Instead of characterizing Oppenheimer and exploring him as a person, his life stages are rattled off in a dramaturgically clever arrangement, jumping around in history – oscillating between ascent and apparent descent; ultimately culminating in an unnecessary plot twist that asserts a two-sided rise of a hero of the nation. But the man, his thoughts and his feelings remain largely empty and powerless despite the pitiful attempt. Three hours in and I’m still wondering: who is this man? Why should I know his story? Likewise, the movie completely fails to come to terms with the atomic bombing and the flimsy hounding by politicians. It hawks the misanthropic event as the gesture of an individual and not of a political system.

The movie Oppenheimer is therefore more like an apolitically abridged Wikipedia article whose chapters have been jumbled up and read aloud as a high-quality audiobook that makes your ears prick up. But the movie doesn’t really offer any additional value in terms of contemplation and emotional devotion. Just a dazzled, shoulder-shrugging “Uff … Well, so-so”.

Ergo: Unfortunately, unfortunately, just a product of the Hollywood machine, which naturally shines and impresses at first glance, but on closer inspection has no sensitivity, no engagement, no courage. An over-stylized product without inner life, without character, without sustainability. This is not the heart of a carpenter, but that of a purely materialistic engineer.

I bet that in ten years the movie Oppenheimer will be forgotten, even if it is not formally a catastrophe.

Conclusion

Cold art .. but with a BANG!

Facts

Original Title

Length

Director

Cast

Oppenheimer

181 Min

Christopher Nolan

Cillian Murphy as J. Robert Oppenheimer

Emily Blunt as Kitty Oppenheimer

Matt Damon as Leslie Groves

Robert Downey Jr. as Lewis Strauss

Alden Ehrenreich as Senate Aide

Scott Grimes as Counsel

Jason Clarke as Roger Robb

Kurt Koehler as Thomas Morgan

Tony Goldwyn as Gordon Gray

John Gowans as Ward Evans

What is Stranger’s Gaze?

The Stranger’s Gaze is a literary fever dream that is sensualized through various media — primarily cinema, which I hold in high esteem. Based on the distinctions between male and female gaze, the focus is shifted through a crack in a destroyed lens, in the hope of obtaining an unaccustomed, a strange gaze.

-

Creating Rem Lezar .. or: The Heroic Nature of the Wishing Machine

What is it about?

Two children disillusioned with life give in to the illusion of a superhero. Only to realize that this illusion can come true.

What is it really about?

Creating B-movie culture

The video store culture of the 80s and 90s created a monster without equal: An unyielding, almost unconquerable production factory for ludicrous movie snakes that never made it into the hearts of cinemas due to their can-pound-sized budget pots and questionable qualities, but received their baptism in the cathedrals of the video cassette shelves and flooded the shelves there. Such disposable consumer goods undoubtedly included mostly the cheapest baller and horror junk (and of course porn movies), most of which were (rightly!) swallowed up by time. Nowadays, however, it is overlooked (probably due to trauma) that among the direct-to-video productions there were also vast numbers of children’s films, which in their sheer mass of unnecessary, trivial and, to make matters worse, mediocre sequels lulled the undemanding young human clientele (surprise: there are 19 films of “In a Land Before Our Time”!). So many children’s films were produced for the video stores that it was even decided to allow access to the hallowed halls of VHS only from the age of 18 (maybe I’m lying, but hypothetically completely plausible!?).“Creating Rem Lezar” is one such children’s film produced for the video stores, but it must have flopped mightily at the video store cash registers at the time and only achieved its deserved fame and cult status through the gradual rediscovery of the Internet. Unfortunately, the cult is celebrated in an ironized “so bad it’s good” way that breaks my heart into a thousand and one pieces. Sure, I’m not kidding myself: Creating Rem Lezar is a kid-friendly musical movie with catchy but also cringy 80s-poppy warble interludes, somewhere between commercial jingle and on-hold music. With stiff amateur acting. With costumes on a small-town carnival level. With pale lighting based solely on natural light. With pixel-guaranteed special effects that make the “special” “special” by the frown-inducing nature. Just like the rather matt look instead of high gloss. There’s a lot that you could rant and rave about Creating Rem Lezar. But … after my euphoric viewing in a mental stupor, I looked deep into the sad eyes of the video store god and clearly recognized my mission: to spread some love for the film so that it finally gets a fair reputation. Because it deserves that. And I don’t mean that in a self-indulgent, ironic way, but really seriously! There’s far more to this movie than meets the eye at the beginning.

But speaking of the beginning: let’s first rewind.

A cinematographic dream of dreaming

The story is very simple: we have two children, Zack and Ashley, who find their fantasy-filled childhood in the typical US “more of the same” small-town idyll a monotonous, meaningless hell. A mentally imprisoning illusory idyll based on social rules and norms that chain them up as children until they are mentally and physically impoverished so that they can become good adults. In fact, the very adults who currently hold authority and power and hammer this joyless doctrine into children’s heads. This is a world without fantasy, without dreams, without variability, but a closed cage of the fatalistic seriousness of conservative adult reality. But Zack and Ashley, both rebels against the establishment, are haunted in their dreams by a consciousness animator in a blue and yellow spandex superhero costume named Rem Lezar, who brings Zack and Ashley together as friends. Through their extraordinary powers of imagination and cooperation, the children manage to animate Rem Lezar and migrate him into their (oneiric) reality. But to give him heroic powers in reality, they must retrieve his mystical amulet (quixotic medallion), hidden by a disembodied bugbear called Vorock “at the highest point the mind can reach”. They have until sundown. They search on skyscrapers, on mountains, but they only find the amulet in love itself. In the love for themselves, in the love for other people, for their family, for their friends, even for their worst enemies. Chiseled into this is the power of the amulet, which then becomes their own and passes to them. However, their adventure turns out to be a lucid dream experience, even if they will have that amulet with them forever after waking up, with the realization slumbering in their hearts that dreams and fantasy have an unimaginable transformative power that extends into reality. Because the world around Zack and Ashley has changed after their shared adventure dream with Rem Lezar – also because they have changed.

The heroic nature of the wishing machine.

It is no coincidence that Zack and Ashley imagine Rem Lezar while dreaming. REM (rapid eye movement) refers to the sleep phase in which we not only snore in a way that is dangerous for our neighbors, but above all dream away powerfully. In all their songs, Rem Lezar and the two children never tire of emphasizing (sometimes in the wrong tones) how much they long for dreaming (“When i’m dreaming my dreaming of a dream”); how they can surpass themselves in dreams and, above all, how dreams can inspire and drive us in waking life.In dreams, our wishes and desires often manifest themselves in surreal, unthinkable and symbolic forms. According to Deleuze and Guattari, the cognitive cinema of slumber is driven by so-called wish machines. It is these machines that project the images, scenarios and stories onto our inner screen that reflect our deepest desires and fears. But there is another power in these ever-rotating wish machines: they can make the unthinkable tangible and lead us into new, unknown territories that are not limited by the structures and norms of waking life. In contrast to their outdated Oedipal colleague Freud, who regarded dreams as manifestations of the unconscious, Deleuze and Guattari see desire as a productive and creative force. For them, desire machines are mechanisms that thus constantly create new connections and realities by penetrating the organless bodies (exactly what one is in a dream: a diffuse, disembodied figure).

Rem Lezar is therefore not simply an arbitrarily associated or repressed fantasy that emerges from the clutches of the unconscious; nor is it a wishful thinking of a prototypical ideal, but an active creation that opens up and, above all, promotes new possibilities and realities for the children. Rem Lezar is thus the somnambulistic wishing machine itself. The children fulfil their wishes and desires with this figure and use it to imagine a new world – entirely according to their real wishes and desires – but also to overcome their fears (characterized by the spectre of Vorlock).

Where dreams sleep.

In this, Rem Lezar stands in complete contrast to the usual superhero fumes that have fogged us for so many years. The superheroes that Marvel and DC unleash on us do not internalize processes to change reality in people at all, but the exact opposite. They want to preserve the infernal (suburban, seemingly idyllic) reality – just as it is. That is why they fight against every threat, every leper and every absurdity that challenges the current reality and questions systematic positions of power. They protect what Mark Fisher calls capitalist realism.In the “superhero versus villain” battle, there is no dialectical confrontation between hegemony and rebellion. The rulers spectacularly eliminate the rebels without a trace, so that everything remains the same. Example: In the case of Gotham City, this is demonstrated time and again: Not only is the city sinking into chaos and violence, but corruption and injustice are also attacked by the anti-capitalist supervillains (e.g. Joker, Bone, ..), so that they come up with alternative (thoroughly questionable) models of society. However, the fundamental criticism of these spokespeople is silenced thanks to the multimillion-dollar Feldermaus guy. The hero who otherwise cleans up the streets of petty criminals but continues to tolerate the large-scale, systematic corruption and injustice of the capitalist pigs. The same applies to the ideological battles of Killmonger in Black Panther, Thanos, Culture, Ozymandias, etc. etc.

Many of the conflicts in these films are aimed at resolving a system-critical crisis that shakes reality and thus restoring the existing social and political order. Obscenely, these stories primarily neglect the ordinary people who are caught up in this order. Ultimately, only the superheroes themselves and their loyal entourage get a chance to speak. When Erika and Max Mustermann are allowed to take the stage, it is only as opinionated weaklings and victims who have to be rescued immediately by the superhero institution at the slightest stumble. People are thus appeased instead of encouraged so that the system can continue to exist. The superhero stories thus suggest a lack of alternatives to which people blindly and silently submit, otherwise worse evil would threaten, although the evil itself has arisen from the system itself.

In contrast, “Creating Rem Lezar” is neither about preserving the system nor about fending off external threats, but solely about transforming reality from within (from the people themselves). The manifest wish machine Rem Lezar encourages children in an educational way to live out their wishes and dreams and translate them into reality. In the music-style collaged song “We’ve got it all”, Rem Lezar also teaches the children that this transformational power (wish machine) exists in each of us and that everyone can transcend themselves and that we must share this experience with each other. In doing so, he proclaims a non-classical, equal principle of solidarity that does not divide us into the categories of victim and hero, but rather on an equal footing and power-free cooperation.

That is why Rem does not dictate a worldly paradigm to the children, but lets them formulate it exploratively and dialectically; for example, when Zach and Ashley consider what this highest point could be and they have to realize that the “highest point the mind can reach” is not the former World Trade Center (as an iconography of capitalism), but that this point can be discovered within ourselves.

Rem Lezar enables these children to believe in themselves, to consciously perceive and appreciate themselves and their fellow human beings, their environment and to recognize the full potential of their imagination and to let it interfere and synthesize with reality (deterritorialization) in order to create a new reality according to everyone’s own wishes and desires (reterritorialization). So instead of submitting to or even defending the existing order, they can finally live freely and in harmony with themselves and reality.

Becoming instead of escapism.

The ideological differences between “Creating Rem Lezar” and the usual superhero films reflect different attitudes towards change and stability. Iron Man, Batman, Captain America & Co. perpetuate a simplified and rigid world in which changes are caused by threats, but “fortunately” neutralized by the heroic deeds of these supermen in order to restore the good old order for the little man. “Creating Rem Lezar”, on the other hand, affirms an ideology of becoming and creation that arises from inner dreams and desires. It offers a vision of change that is not forced by external conflicts, but made possible by the creative power of inner desire.In this way, the film inspires us to perceive and influence our world with a more open and creative mind (the mind of a child).

Who can look at this movie with irony and degrading sarcasm?

And fittingly, Richard Sanderson has already sung: Dreams are my Reality. Rem Lezar would say: Dreams are our Reality.

Conclusion

It is not a movie. It is an experience.

Facts

Original Title

Length

Director

Cast

Creating Rem Lezar

48 Min

Scott Zakarin

Jack Mulcahy .. Rem Lezar

Courtney Kernaghan .. Ashlee

Jonathan Goch .. Zack

Kathleen Gati .. Ashlee’s Mother(as Kathi Gati)

Scott Zakarin .. Vorock

Stewart H. Bruck .. Principal

What is Stranger’s Gaze?

The Stranger’s Gaze is a literary fever dream that is sensualized through various media — primarily cinema, which I hold in high esteem. Based on the distinctions between male and female gaze, the focus is shifted through a crack in a destroyed lens, in the hope of obtaining an unaccustomed, a strange gaze.

-

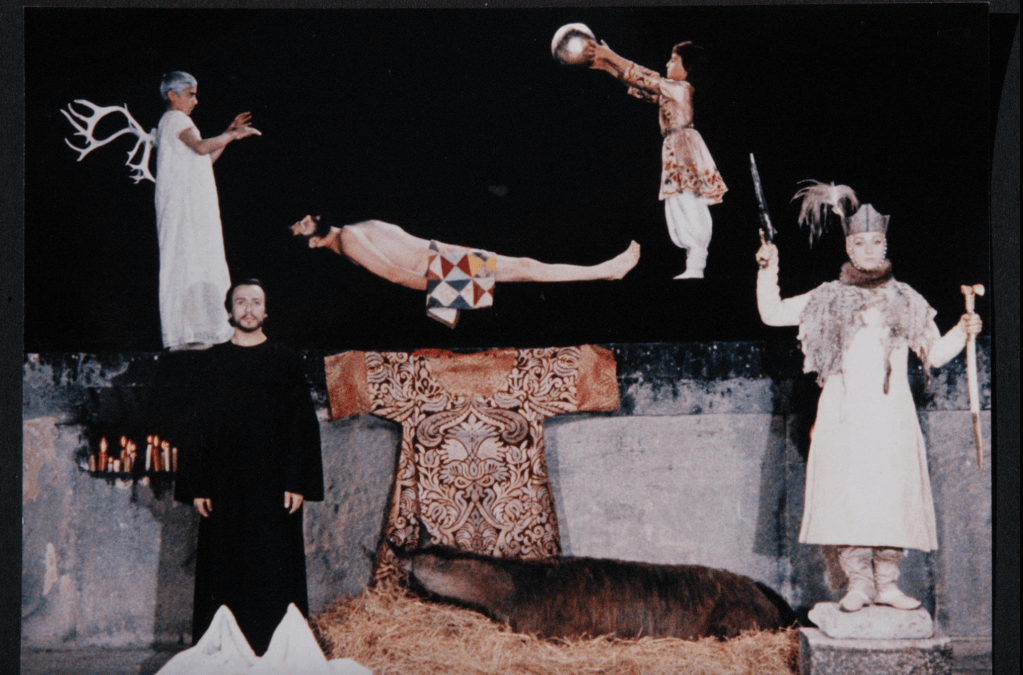

The Color of the Pomegranates .. or An hyper-aesthetic Biography.

What is it about?

This is not a biography. It is a visual ode to the life of Sayat-Nova, an Armenian poet, weaving a mesmerizing tapestry of his journey through symbolic imagery and poetic storytelling. Each frame is a vibrant canvas, painting a portrait of his life, from childhood innocence to artistic brilliance, in a lyrical and spiritual exploration of identity and culture. This film intricately melds art, history, and the essence of human existence into a breathtaking cinematic experience.

What is it really about?

Sayat Nova: The king of song. A poet with incomparably acrobatic word stitches of the Armenian language, Georgian, Azerbaijani, Persian and Arabic, crocheted in the finest, most delicate harmonies of the musical carpets in which he wraps himself and protects his listeners from the dirty desert sand.

His child: a blossoming in the rain-soaked monastery libraries, the sacredly scooped walls, when after a torrential downpour the devastating amniotic fluid has to be squeezed out of the drunken writings so that every word and every sentence of these writings are protected and do not blur obscurely forever. These writings, squeezed like oranges, a boy guards and gives them to the sun god to read as they spread their leaves like angel wings and beat with the wind, drumming out a sound from the liturgies and allegories the boy hears them sing together. In the silent moments that follow, slumbering in the daily chores and ablutions, promising whispers shimmer forth; the rustle of shells on milky, faded breasts.

His youth: a bulbous lute whose plucked strings set the world and her ears vibrating, the instrument of elegiac compatibility, gently carried by a boy who translates his inner world musically and poetically into lute playing, eagerly reproducing the former angelic sounds of writings flapping in the wind. Having grown up in a hormonal frenzy, the boy gives his mood to a young man and shortly afterwards merges with the young man himself. Behind a white veil of innocence, a young woman masks her flirtation. With elegantly waving fingers, she crochets the tip of her veil into an impenetrable fabric to keep her innocence eternal, but she separates all the threads of her veil when the young man sends her his ear-pleasing lute playing and his eloquent poetry. The veil of innocence is lifted, the mask disappears and her face floods the room with her heart. As a breeze blows through the agitated room at dusk, not only has the woman slipped away from the veil, but also the young man from his lute and his poems.

His life in the princely court: a courtly spectacle among princes and dukes, swaying in a tumbling dance, dully rattling their sabres, circling around the root-like antlers of killed sacred stags, obeying the sound of their prince’s pistol at every turn and becoming amusing caricatures of themselves. Soundlessly, the lamentation of poetry degenerates into a diaphragm-slicing theater. But the fire in the longing-suffering young man blazes with every further pulsation in his veins, leaving behind heartbeat after heartbeat a burnt, ashen exterior, a dark robe in which he eviscerates his unrequited love, constantly and secretly wearing his affection like an amulet that burns deeper and deeper into his chest in the blazing fire. And when the object of his desire, the young woman, casts secret glances at him from behind her blood-guilty red veil, what must not be and what is forbidden happens, forcing the guilty man with the burnt heart in his chest to hide his face behind a black veil and bury their shared love forever.

His life in the monastery: in the impenetrable, black thicket, a single monument shines out, a monastery to which the young man sacrificially devotes himself, shedding his robes, his longings and desires, chagrined never to be more than a mute and celibate clergyman among mute and celibate clergymen, he, a priest and the other monks, whose desires culminate in the passionate, lustful consumption of pomegranates, feasting on them and indulging themselves. A monastery supported by pillars of ceremonial. Devils are banished from the pores of the skin in ablutions. Intoxicating juices are fermented from the sweet grape fruits. Prayers for the dead, marriages under white veils, baptisms. A concatenation of human moments, in the sacred halls of this house of God, enclosed by holy water that flows like wrists in underground corridors, gushing from cracks in the walls and quenching the thirst of the clergy.

His dream: a mechanical, golden-steel hand that reaches into the body of thought and weaves a new one from the universe of feelings and memories, turning the gaze to childhood and youth, even mirroring the paternity of his own father to his son with his own paternity, while the long-dormant mother, holding hands, gives birth to a united smile. In the unconscious imitation of the father, childhood and old age merge with the symbolically hewn stones that decorate that monastery of then and now, in the comforting trumpets of the wandering musicians, which made the children’s ears grow and in those torn and dyed sheep’s wool gave the wearers an ornamental being and nourished and warmed both young and old. It is both an arrival and a farewell.

His twilight years: exhausted by memories, the monastery lingers with dry eyes and dry watercourses, letting itself be embraced by plants like a Faustian force of nature. The wandering faces are devoted, sacrificing their blackest coats to beg for forgiveness and hope in pure white robes; they sharpen their knives on sheep and goats at the same time to soak the stone floors of the monastery with blood so that the life-giving water finds its way back into the furrowed monastery walls, torrent-like, to free the dry, thirsty throats from their stranglehold. But the stranglehold turns into severed heads, severely beaten by foreign enemies who fight battles against God and against the defenders of God, finally even tearing the face of God from the skull of the monastery, until the monastery lies in shambles, ruined and destroyed.

His encounter with the angel of death: In the remains of the monastery, the stained-glass windows with golden frames, the half-shattered foundations resting firmly in the grass-clouded ground like Stone Age gravestones, angels drift about, paying homage to the last works of art that did not fall victim to the enemy. But it is too late. A woman in white is lowered into the fertile ground. The mother? The love? Innocence?

His death: the last drop of a butchered pomegranate flows from the sullying sword. The time has come: walled in between endless crosses, the man sheds his last cloak and resignedly sacrifices himself for the encounter with the archangel, who showers him with the unctuous juice of the pomegranates, immerses his aged form in a bloody fire until his own youth hovers angelically above him and ushers in his last breath, expelling the breath of God. A painful ceremony, like the chickens that have had their heads cut off and are still writhing against death, until the candles of life are blown out by the wild fluttering. At dawn, when the smoke from the extinguished candles still rises to the sky, the farewell follows and the lute that the man, the king of song, once played so artfully, which now sticks out of the freshly closed grave, does not remain eternally with the buried, but is taken by angels who carry it into the world. While man passes away dead in infinity, his art still resounds eternally.

The Color of the Pomegranate: An artificial, strictly arranged work of art that pays homage to the poetic and compositional act of creation of the Armenian Ashyg Sayat Nova in an eye-pleasing way in over-aesthetic tableaux vivants and still lifes. It is supposed to be a biography, but any stringent narration of the biographical has to make way for momentary and rather associative life situations. So instead of retelling Sayat Nova’s life, his artistic life is brought to life with an artist’s reel of interpretation. Director Sergei Parajanov interweaves poetry and musical composition by creating a visual language that resembles an eloquent volume of poetry and using aesthetic leitmotifs and visual elements like recurring melodies, creating a film that feels extremely coherent by combining the worlds of art. A film in which we learn nothing about Sayat Nova’s life, but more about what his life felt like.

The Stranger: The Stranger rattled in amazement as the 75 minutes ticked by and now understands why The Color of Pomegranates is such a significant source of inspiration for so many artists. Through the radicalism of what is shown and the sensuality evoked in the viewer, it feels as if the rather moderately arty cardboard box between the ears is flooded with intimately hidden ideas that one wants to live out devotedly before the box bursts and everything floats away. The film is therefore an extraordinary encounter, a wild, innovative and inspiring journey into an enviably artistic world of thought full of aestheticism and sublimity.

Conclusion

It is not a movie. It is an experience.

Facts

Original Title

Length

Director

Cast

Նռան գույնը

80 Min

Sergei Parajanov

Sofiko Chiaureli as Poet as a Youth…

Melkon Alekyan as Poet as a child

Vilen Galstyan as Poet in the cloister

Gogi Gegechkori as Poet as an old man

Spartak Bagashvili as Poet’s father

Medea Japaridze as Poet’s mother

What is Stranger’s Gaze?

The Stranger’s Gaze is a literary fever dream that is sensualized through various media — primarily cinema, which I hold in high esteem. Based on the distinctions between male and female gaze, the focus is shifted through a crack in a destroyed lens, in the hope of obtaining an unaccustomed, a strange gaze.

-

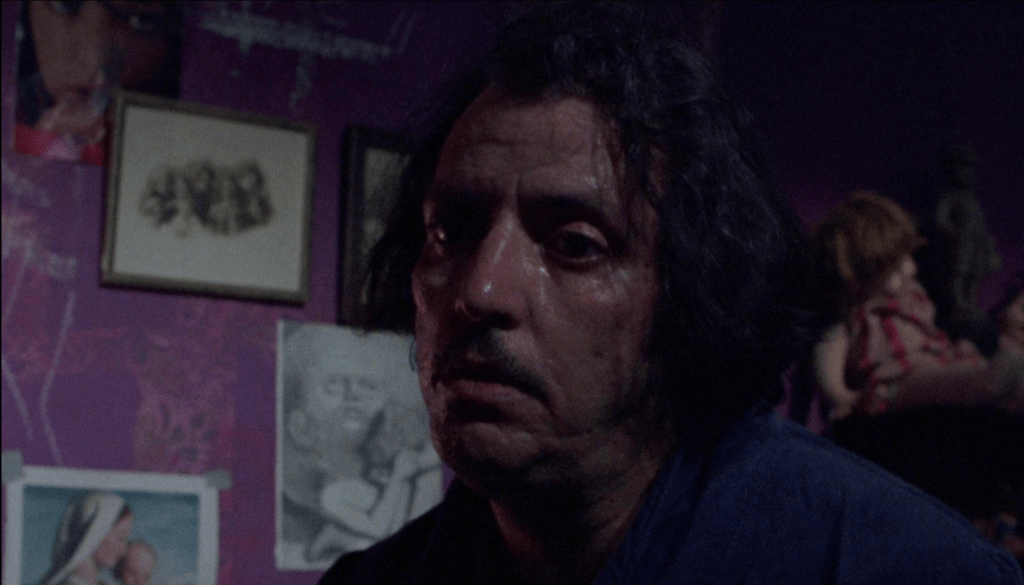

Maniac. (1980) .. or The Poetry of a Serial Killer.

What is it about?

A young man, who carries the traumas of his childhood around with him like his thinning hair, goes out of his way to murder young women. Even his love for a woman who has serious feelings for him cannot curb his desire to kill.

What is it really about?

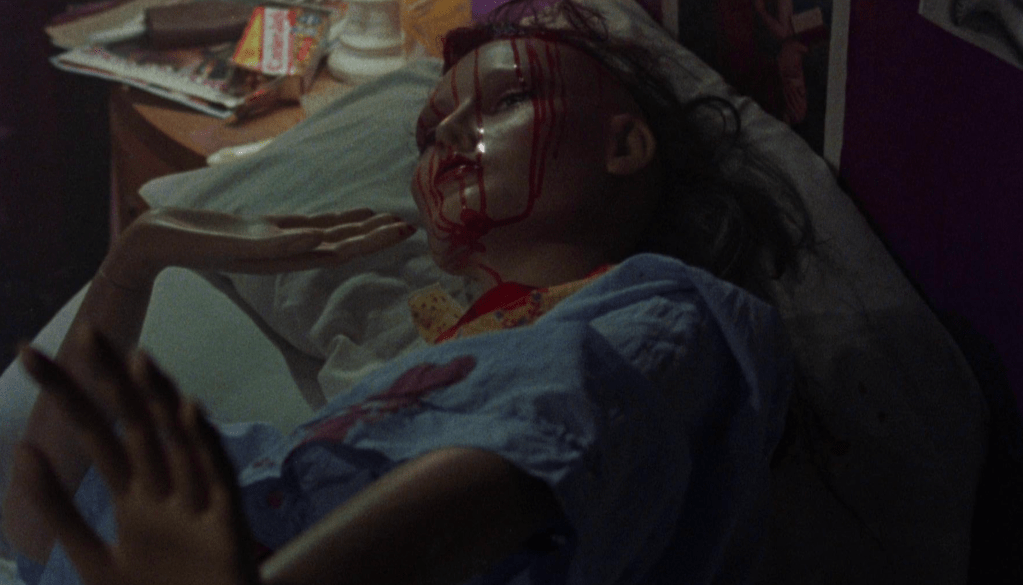

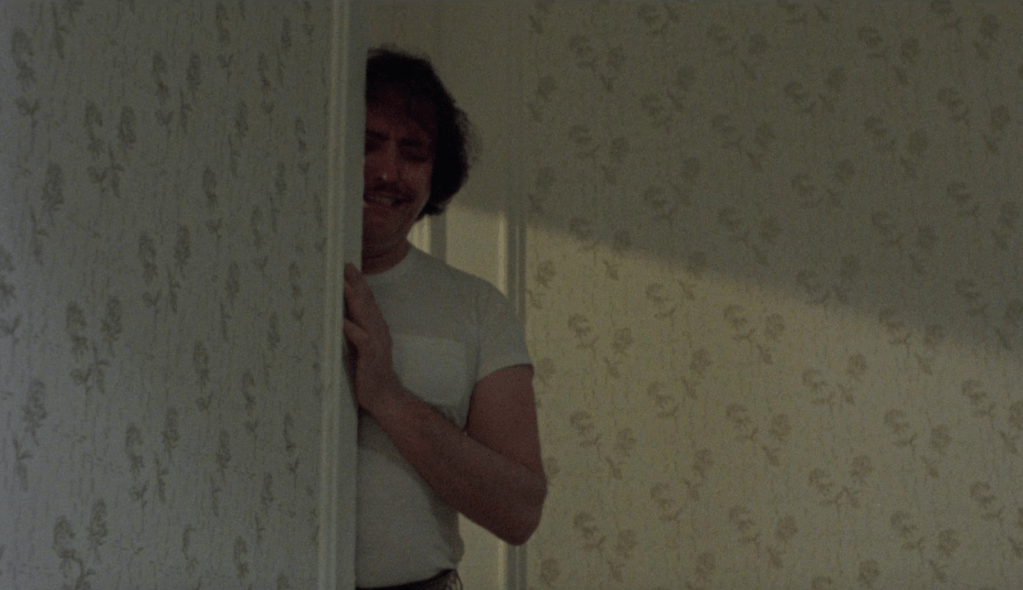

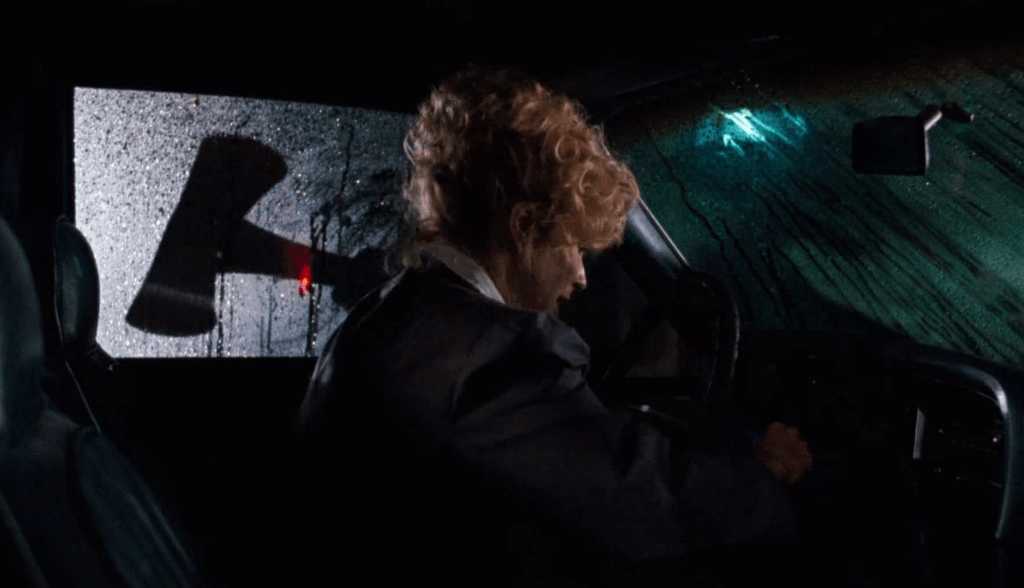

His skin is covered in burn scars, because the cigarette his mother took a drag from glowed hot on his skin. Back then, when he was still small and the wounds were still freshly covered with a scab, she wandered around after the intoxication of love that she thought she found in men. He stayed in the bathroom, stayed there because she had locked him in to make love. He stayed in the bathroom, the place where you shit the dirt out of your body and wash the dirt off your body. As if he himself were pure filth.

His body is chunky, sluggish and misshapen. His breath a puffing rattle. His shoulder-length hair bears the sweat of the previous night. His fingernails are nibbled short. His pale skin shines greasy between the sprouting body hair. The areas of his body that don’t shine are dominated by burn scars. Burns from an ancient past that still burn all the way to his chest. Every morning, when he rouses himself from his nightmarish sleep, he always looks at those scars to see if they are still there, if the pain in his chest is still there. And then he goes out.

His dwelling, nowhere in New York City, is a niche-like, windowless room in which a neglected television is blaring away. On the purple-painted walls hang erotic pictures of women, but torn in the places where the intimate intoxication of love is lusted after. In the torn pictures of women, the purple of the wall, the color of death, now covers the women’s intimate areas. Mannequins with their rigid bodies and dead eyes are his only company.

His demeanor is friendly and polite. The neighbor in his house doesn’t suspect what kind of schizophrenic monster dwells behind his friendly nature and scars. Nor does the prostitute he asks to pose like a model in a photo shoot; just like the moment when the flash captures the female body standing rigidly in a pose like a mannequin. But as soon as the purchased intimacy between him and the prostitute has to be redeemed, he loses his mind and his beautiful mother appears to him in the uninteresting face of the prostitute, whom he chokes and strangles, choking madly until her last cries are drowned out by his guilt. Then he scalps her. And with the scalp, he immortalizes and preserves them in his dwelling when he pulls the bloody, blunt hair of the dead woman’s head over the bald head of a mannequin and nails it down, panting.

His wild rampages and killings terrify the whole of New York City. He chooses his victims seemingly without motive. But it’s the people’s busy, dirty lust that tempts him to strangle, shoot and stab. Just as his mother was once lost in a dance of sweet sweat and semen, while he was stuck in the room where she had previously made herself beautiful and where her perfume and the penetrating scent of toilet freshener floated in the air and beguiled him. For him, this is an ugly, depraved city for ugly, depraved people that seems to live on the night. Where there seem to be no policemen, no civil courage. But it is teeming with voluptuous people who give themselves over to sexual lust. Or, like him, the lust for murder.

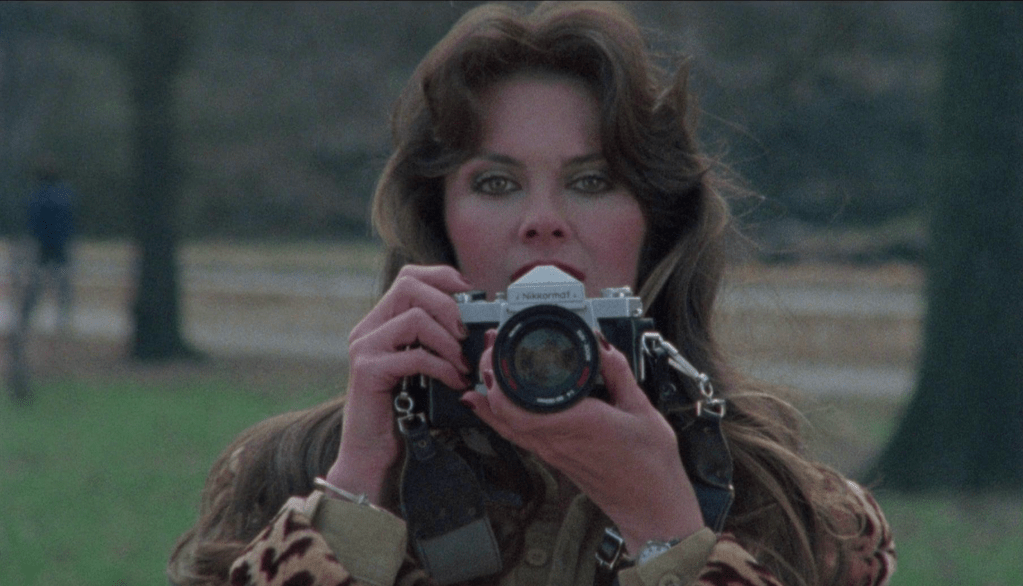

His schizophrenia behind the burn scars seems to be tamed only by a female photographer, because she also preserves the women around her with a camera that lights up like a flash when he fires, just like his shotgun. She objectifies people for her art, just like the dead woman, scalped and reborn in the mannequins that keep him company. And only the photographer manages to escape his murderous hands; she, who looks like his mother, to whom he is still submissive; in whom his schizophrenia first rises when the photographer kisses him maternally and begins to condemn him when he gets the feeling he is about to be locked back in the bathroom by the disappointed, evil mother, while she writhes in lust with all of New York City.

His sacrificial catharsis ultimately stimulates the woman who looks like his mother, while all evil, all shame and psychological filth was poured over him by the woman who was his mother. And the sacrificial ritual ultimately bears witness to the company that shared his dwelling with him, rigid and dead, as mannequins; who never uttered a single word of contradiction or snuggled up to him erotically, but always stood by his side in confidence; which for them, however, was hell, locked up in these eternal mannequins, objectified and on display; existing solely to satisfy the shame-filled gaze of an impotent, sad, terrible man.

His violence as a display of his sinister nature does not turn him into a mannequin but rather into a puppet of thrill, disgust and shock, when the observation and persecution of the victims is shown and observed by us viewers in tense scenes lasting several minutes. When the synth sound assaults our ears and the camera hovers elegiacally around the brutal events. Always close to the eponymous madman and what makes him mad.

Conclusion

A nasty movie about a nasty but also pitiful man.

Facts

Original Title

Length

Director

Cast

Maniac

88 Min

William Lustig

Joe Spinell as Frank Zito

Caroline Munro as Anna D’Antoni

Abigail Clayton as Rita

Kelly Piper as Nurse

Rita Montone as Hooker

Tom Savini as Disco Boy

What is Stranger’s Gaze?

The Stranger’s Gaze is a literary fever dream that is sensualized through various media — primarily cinema, which I hold in high esteem. Based on the distinctions between male and female gaze, the focus is shifted through a crack in a destroyed lens, in the hope of obtaining an unaccustomed, a strange gaze.

-

Cobra .. or Stallones Version of Beverly Hills Cop.

What is it about?

Stallone gets into his son’s wardrobe to dress up as a tough cop and stroll around dark Los Angeles to catch the Night Slasher. Yeah, and there is Brigitte Nielsen, because .. yeah, she is in it, doing things, ehm, yeah.

What is it really about?

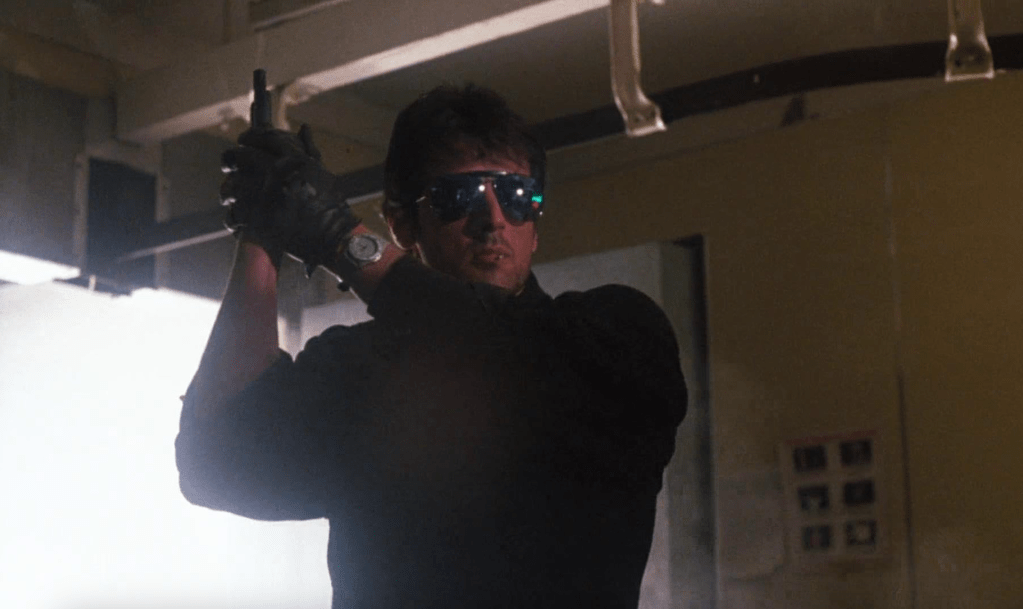

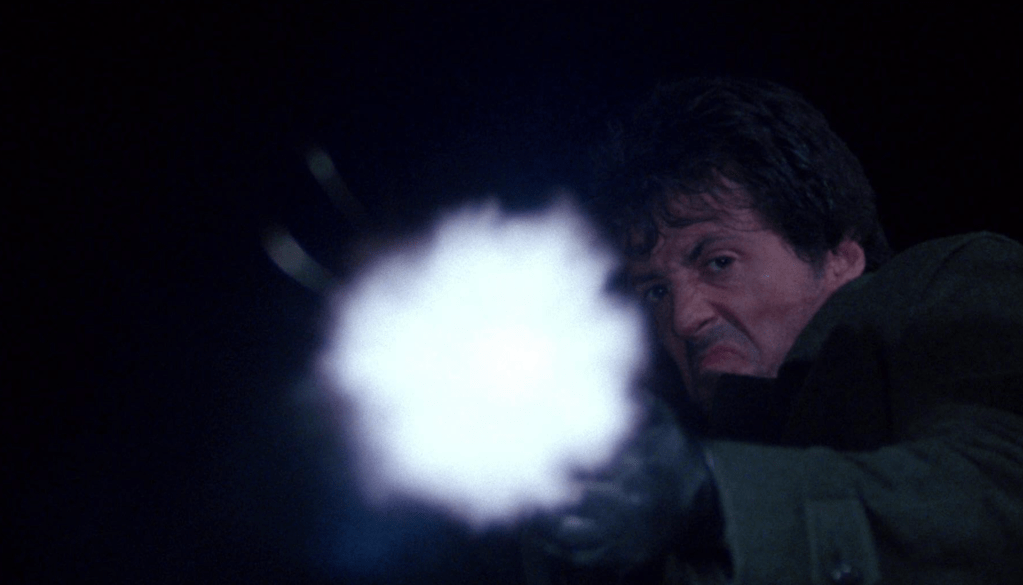

L. A. 1986. When a city is ruled by outlaws, a cop has to become the law himself. His name: Cobretti, or in short:

Cobra.

He is the medicine for the disease called crime. And the city is a sick juggernaut that can only be cured by him … that must be cleansed by him. Because when Cobra judges, the murderers don’t end up in the dock, but six feet underground. Cobra wields his judge’s gavel like no other to knock down the scum and with his grenade-strong paragraphs he sends them straight to hell.

Cobra.

His latest case: The Night Slasher and his henchmen. Wearing masks and wielding knives, they prowl the nightshade, slashing innocent citizens with relish. Only the permed face Ingrid (Brigitte Nielsen) was able to escape them before her hair was cut short. She also has a secret: she is an Amazon-like barbarian because she dips her chips in ketchup until the potato sticks look like blood-stained fingers. Despite this and her marginal acting skills, she is protected by

Cobra.

He, the empathetic creature with the concrete face. He may hide his face behind sunglasses (like criminals hide behind masks), he may also hide his identity under leather gloves (like burglars do) and behind his irresistible coolness, and yes, he may be as ruthless as that and share cold slices of pizza with scissors, but he can’t hide his true self forever.

Cobra.

For just as a cobra follows the flute of its snake charmer, Cobra dances to the tune of crime, for without crime his law would be a crime against humanity – only with the crime of others does he find legitimization for his own crimes.

Cobra.

And not only that. In truth, he is also a prepubescent boy, disguised as a childishly fantasized image of an adult. Although women lie at his feet, outside of his gunfights he meets them with a childlike innocence and shame. He can only return a kiss fleetingly if he can flee to his Colt immediately afterwards. If only to scrub the phallic gun barrel. And when Cobra drives off with Ingrid on a motorcycle, I’m sure that he really only drives her home to drop her off at the front door without sipping a coffee with her upstairs.

Cobra.

The world in which he exists at all is a hypermasculine boys’ fantasy, imagined at an age when boys chase each other as cops and robbers and shoot each other with foam bullets, at an age when girls are bad; at an age when one internalizes one’s own physical weakness in relation to men, who are stronger and more powerful, in a completely exaggerated way. A phantasm that exaggerates unattainable (thick biceps, permanently available fast food) or even forbidden (heavy guns, fast cars) image elements for boys. In which there are simply no girls, because in this game called crime and street only the archaic solutions – namely physical strength and materialism instead of words – count.

Cobra.

But because it’s a boy’s fantasy, it’s also a trip back to childhood for the grown men. A time when not everything was serious and hypercritical. A time when it didn’t matter whether you had to wear a tie at a job interview or were allowed to hand over a bouquet of lilies at a funeral. A time when everything seemed so carefree because any repercussions only lasted until the end of the two-week house arrest. A time when solutions were simple – precisely because the problems were so simple.

Cobra.

See Sylvester Stallone as Cobra and Brigitte Nielsen as Ingrid. In the incomparable 80s cult film by George Pan Cosmatos. With an absolutely irony-free screenplay by Sylvester Stallone, which – mainly because it is so unironic – throws the man back into being a boy. With cool, memorable oneliners, comic-like characters, countless explosions and gunfights. A movie that was unfortunately cut up by the real night slasher, the MPAA, because the original version of the movie was too brutal and self-righteous. Nevertheless, the movie still offers incredible entertainment potential, especially thanks to the handmade action and a man, his fat gun and cool sayings as a universal solution for everything that shakes law and order, in a way that could only be shown on the big screen with a serious face in the 80s and 90s.

Conclusion

Feverish boys dream, full of Action. Action! ACTION!

Facts

Original Title

Length

Director

Cast

Cobra

87 Min

George P. Cosmatos

Sylvester Stallone as Marion Cobretti

Brigitte Nielsen as Ingrid

Reni Santoni as Gonzales

Andrew Robinson as Detective Monte

Brian Thompson as Night Slasher

John Herzfeld as Cho

Lee Garlington as Nancy Stalk

What is Stranger’s Gaze?

The Stranger’s Gaze is a literary fever dream that is sensualized through various media — primarily cinema, which I hold in high esteem. Based on the distinctions between male and female gaze, the focus is shifted through a crack in a destroyed lens, in the hope of obtaining an unaccustomed, a strange gaze.

-

Athena .. or Fighting Fire With Fire.

What is it about?

After the death of a teenager, the young people break out of the banlieues to open up the rift in society. What they tear out are the fundamental problems of contemporary France. The French revolution that starts … and dies.

What is it really about?

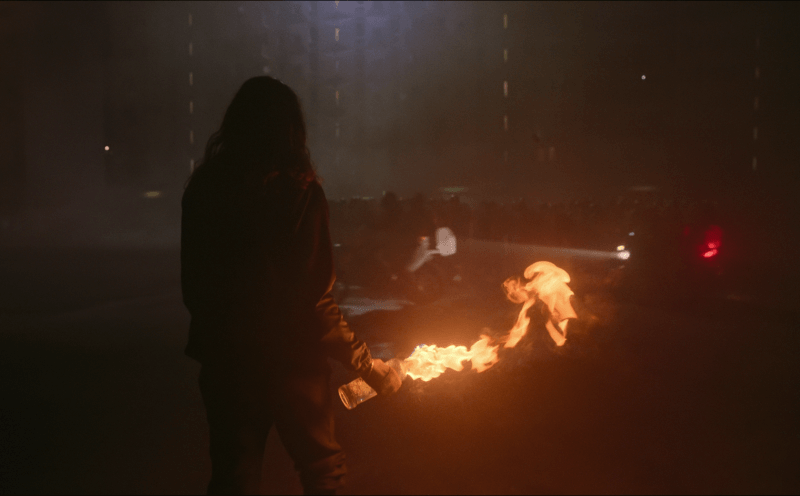

Once, my memories of this still scream in my ears, I succumbed to these thousand and one open wounds that constantly stabbed through my body and what haunted it as a spirit. Not a single droplet of blood came out of the wounds, for I felt completely bled dry by the vampiric authorities, rulers, authorities who shimmered in the socio-economic cosmos. And their long shadows blocked my view into the light, whereupon I searched as a loose silhouette for a plaster to staunch the wounds. I found it wherever I went. In front of my feet. On the streets that were paved with the broken stones of those ruined buildings that they had let wither next to the paths and that they had dismantled stone by stone for a common future on which we were to walk; but which were only ever trodden by them. And what could I do but loosen the plaster with a screwdriver, take control of the plaster to heal my own wounds. But as I disappeared with the plaster in my hand into the neglected, streetlamp-strewn alleyways that I considered my home, I left behind me only new open wounds. On the streets that were no longer paved, but potholed, hollowed out, and on which no one could now stroll lost in thought without breaking their heads, legs and arms.

To my amazement, the gaping wounds widened instead of healing. Even the plaster wasn’t enough for them. So I tried to burn out the wounds. With bulky waste, garbage containers, building fences that were carted in, piled up in a heap as high as the Tower of Babel, high enough to light a fire under the asses of the self-proclaimed gods and warm us up on their burning bodies and burn out the wounds. And even though it lit up all the darkened streets, the fires ultimately left only paltry scars.

I lay there completely paralyzed, disillusioned and hopeless, not daring to look at the open wounds and countless burn scars without plunging into an eternally paralyzing stupor. I couldn’t bear to see the wounds and scars reflected in the shop windows; shop windows in which they displayed their pompous and dapper evening gowns for their hypocritical Caritas galas and the strictly choreographed TV appearances. Entertainment to keep you down. So I took stone after stone and plaster after plaster in my furrowed hand to shatter my reflection and their illusory images in the window panes. The memories of my wounds and scars briefly disappeared in the shattered image. But in the midst of the shattered glass, even the most graceful face was transformed into a distorted grimace. Including mine, which had perhaps always been a grimace.

Not to mention those others who struggled to find cures with empty words. We woke up many an afternoon sleeper with our megaphones or covered up existing street signs with our banners.

I was never alone. A mob gathered around me, I gathered around them. We, the wounded, the miserable, burnt out, wounded. I soon heard all the sirens of the authorities in the angry shouts of that mob. With blazing flames in my hand, I wanted to run closer to them to hear them better and to silence them so that we could be elevated, but I stumbled over the millions of holes in the ground. And because the path was blocked by meters of flaming fire, I had to take a detour. On the detour, I was startled by myself in a shattered shop window. My heart stopped in shock. It just stopped. And then – in the distance – I heard the echoing slogans “Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité” being bludgeoned to silence by the batons of the authorities. This was the rebellion that carried the breath of revolution, but revolutionized nothing.

This is Athena, the banlieue in whose concrete prison we grew up, in which we imbibed the mother’s milk of Athena; she, the goddess of wisdom, strategy and struggle, of art, craftsmanship and manual labor, and goddess of protection. And we her illegitimate children. When one of her brothers is killed, beaten to death by men in police uniforms, we form up to demand justice. Just as the biblical Talion formula says: “Life for life, eye for eye, nose for nose, ear for ear, tooth for tooth”.

We take the authorities by surprise in a furious act of rebellion. The counterattack, after they have beaten us down again and again. A spiral of escalation that cannot end well, a maelstrom of violence accumulating excesses until not only wounds gape, but the wretched flesh behind the wounds bursts out so that they can finally see it and no longer close themselves off from it. This violence is our last chance and Athena is our bastion; the walled-in values of freedom, equality and fraternity are being smashed in their faces. But unfortunately, our rebellion, our revolution, is a rebellion, a revolution against liberty, equality and fraternity. We give up freedom by entrenching ourselves in the narrowest of spaces, seeking protection from the wolves we have attracted; those wolves whom we do not regard as our equals, who do not regard us as equals either. And finally we kill our brothers until all that remains of us is scorched earth, in the hope that it will provide fertile ground for a better future.

This is Athena. This is a hypnotic frenzy that artfully reworks a brutal uprising of the oppressed against their oppressors. The chaotic events quickly come to a head in long, highly impressive plan sequences. The socio-economic explosives are detonated right at the beginning and can be heard as a bang for over 100 minutes. While at the beginning the cinematographic spatiality spreads across an entire district, the production channels itself deeper and deeper into the narrow confines of the banlieues. The social uprising is reduced to a familial one. In the end, it is once again the people in the banlieues who emerge as the losers. Partly because they themselves have allowed it to escalate to this point, because these outsiders only have anger and rage. They have no hopeful values; they can’t even manage to find a common understanding among themselves, among brothers. If that doesn’t work in the microcosm of the family, how can it work in the macrocosm of society? Thus, violence against the authorities ends in self-violence, because they themselves adopt an appropriate attitude of authority like the armed forces against which they want to take action. Only in a destructive, nihilistic motif. The end of the film puts the crown on the whole thing, broadening the narrow perspective to show that this fight is a fight against the wrong enemy and that this fight is a fight to one’s own ruin.

Conclusion

The enigmatic camerawork makes up for weaknesses in the script. Rarely have you been so close to the revolutionary events.

Facts

Original Title

Length

Director

Cast

Athena

97 Min

Romain Gavras

Dali Benssalah as Abdel

Sami Slimane as Karim

Anthony Bajon as Jérôme

Ouassini Embarek as Moktar

Alexis Manenti as Sébastien

What is Stranger’s Gaze?

The Stranger’s Gaze is a literary fever dream that is sensualized through various media — primarily cinema, which I hold in high esteem. Based on the distinctions between male and female gaze, the focus is shifted through a crack in a destroyed lens, in the hope of obtaining an unaccustomed, a strange gaze.

-

Even Dwarfs Started Small .. or A rebellion descends into chaos.

What is it about?

A dwarf uprising escalated quickly.

What is it really about?

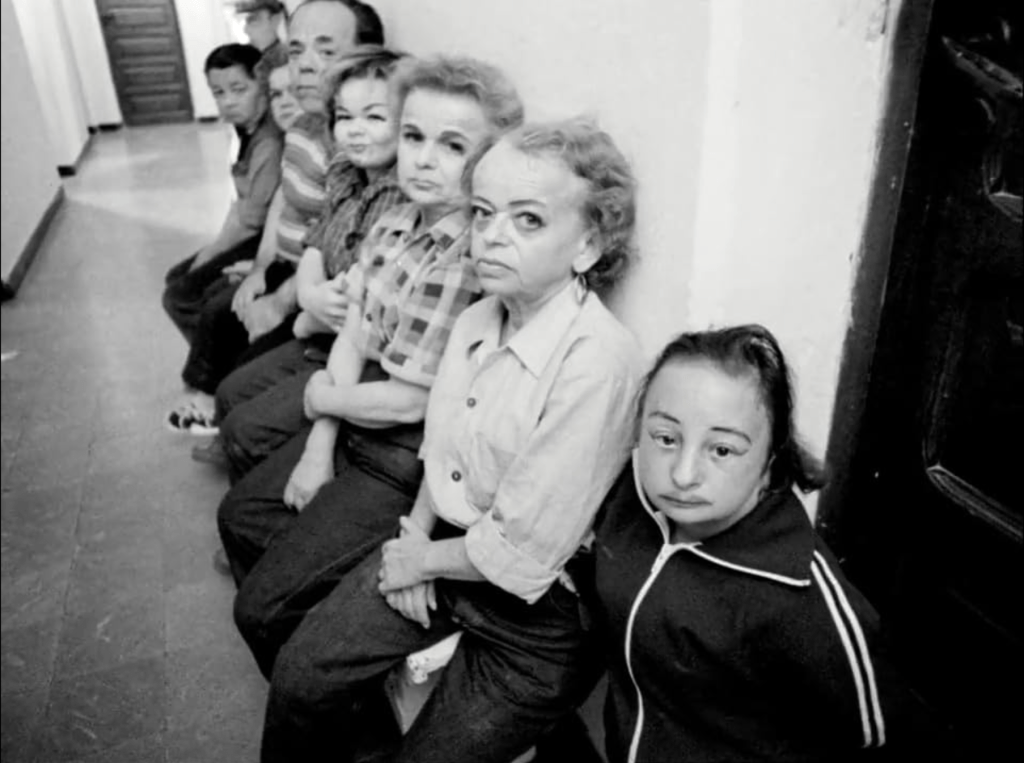

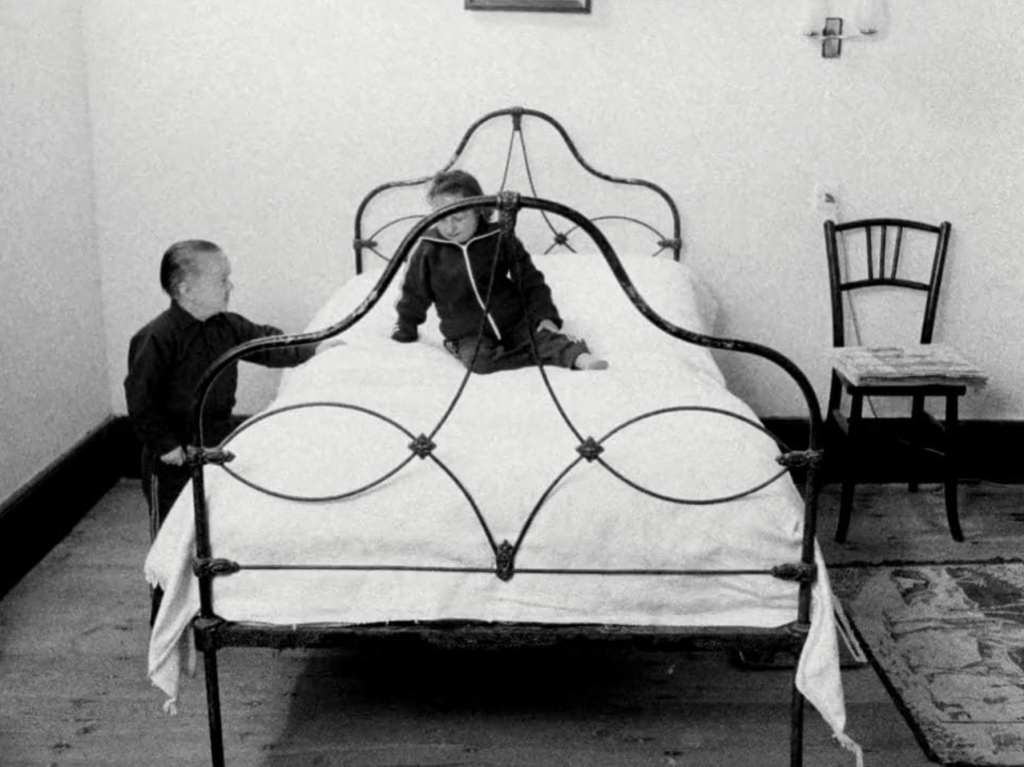

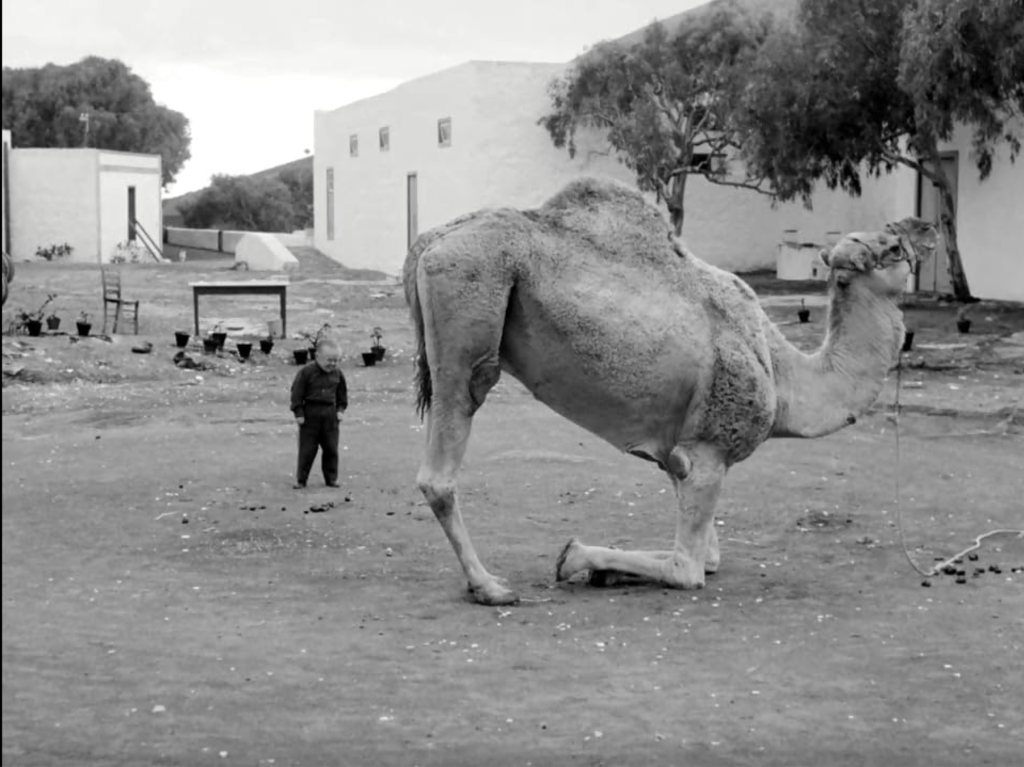

Even dwarves started small. And have grown to the smallest. They couldn’t grow up because they were stuck in children’s bodies, but because they were locked up in an orphanage. At the edge of the world, far and even further away from any normative civilization. Here on Lanzarote. Here in the barren desert landscape, where only the wind knocks on doors.

But then the educators disappear. Are swallowed up by the earth or by the far and even more distant civilization. Appear to be on an excursion. A vacuum of power, in the burnt caramel of the sugar bread and the extinguished echo of the whip, sucks the human, the all-too-human out of the low-rise buildings. Where nothing reigns, chaos reigns, causing the orphanage to tremble and the remaining little ones to awaken from their cockroach-filled sleeping chambers. Those who have been denied an outing. The black sheep among the gentle, the disdainful among the lepers, the neglected among the forgotten. In the sweet, heavy morning dew, they rise above themselves, free of all moderation and order, just as the sun rises over the hill in the cloudless sky. Before the sun reaches the zenith of their hour-long daily march, they try out the dwarf uprising and the anarchic excess of violence escalates.

A sow is slain and the animal world is executed with it. A tree is set on fire, plant pots are smashed and the flora destroyed with them. Blind little ones, as the weakest of the weak, are maltreated for sardonic evil laughter and with them the morality of minority protection is undermined. Despite their reluctance, the little ones are married off by decree of the masses, forced to make love to each other and with them the feeling of love and affection is cynically discolored. A van is short-circuited and misused as a dust-raising ride in the world’s bleakest theme park and technological progress is slowed down along with it. A monkey is nailed to a cross and led through the littered courtyard as a theophoric figure of light, negating all religiousness. The only remaining authority has to hide behind closed doors, is mocked and attacked at the edge of his exile and reason is wiped out with him.

This dwarf rebellion mimes the negation of all values. The rebellion against the universal status quo. The rebellion against a world for which these dwarves only seem to have fallen short; no, this world is too big for them. The view of the big picture is not from a bird’s eye view but from a frog’s eye view. But not only for the so-called dwarves, but also for the tall people. This is a world that people try to tame with rules and walls. A world that is explored and reshaped with hoe and axe, while it responds with avalanches and tsunamis, burying and devouring finite life. A world that wants to be understood with compass and pencil, but forces theorists to constantly erase and repaint the evolutionary spirit of humanity, without ever being able to wear the world formula as a tramp stamp. A world that, due to its unbridled and unbroken perfection, completely overwhelms both young and old. A world that, as a universal authority, dictates the limits of time, the limits of all physicality, the limits of consciousness.

The world cannot be grasped, because thoughts cannot be grasped by hand. For a light to come on, a fire must be lit. To escape from the shadow play of Plato’s cave and, torch in hand, to project one’s own body into the world as a shadow play. Understanding the world means taking the world apart. To break it down into individual parts, to atomize it. Physically and mentally.

The dwarf uprising presented by Werner Herzog is an analogy of the omnipresent attempt at rebellion, which stems from a pure, innate helplessness that is written into the genes of every human being – big or small. From today’s perspective, choosing the transgressive presentation only with the help of people of small stature is hardly conceivable without provoking another rebellion. These Minions on PCP and LSD convey a surreal image of humanity that is both cute and irritating in an unreal way. A vacillation between smiling and shock.

Conclusion

A nihilistic and abysmal film.

Facts

Original Title

Length

Director

Cast

Auch Zwerge haben klein angefangen

96 Min

Werner Herzog

Helmut Döring as Hombré

Paul Glauer as Erzieher

Gisela Hertwig as Pobrecita

Hertel Minkner as Chicklets

Gertrud Piccini as Piccini

Marianne Saar as Theresa

Brigitte Saar as Cochina

Gerd Gickel as Pepe

What is Stranger’s Gaze?

The Stranger’s Gaze is a literary fever dream that is sensualized through various media — primarily cinema, which I hold in high esteem. Based on the distinctions between male and female gaze, the focus is shifted through a crack in a destroyed lens, in the hope of obtaining an unaccustomed, a strange gaze.

-

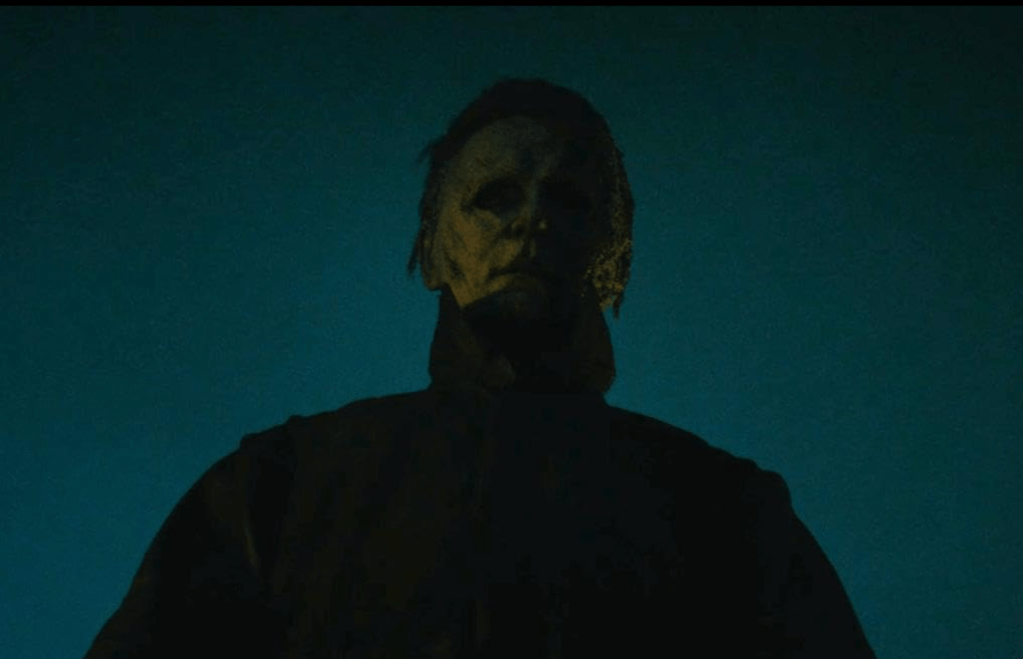

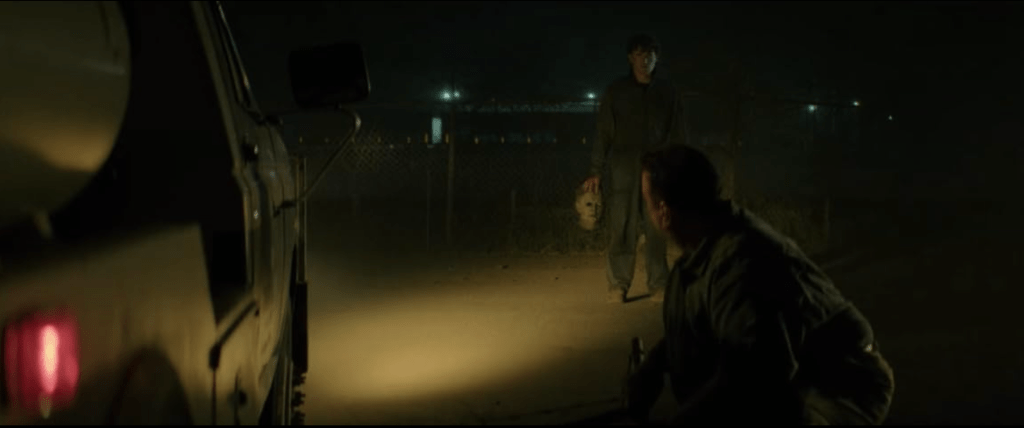

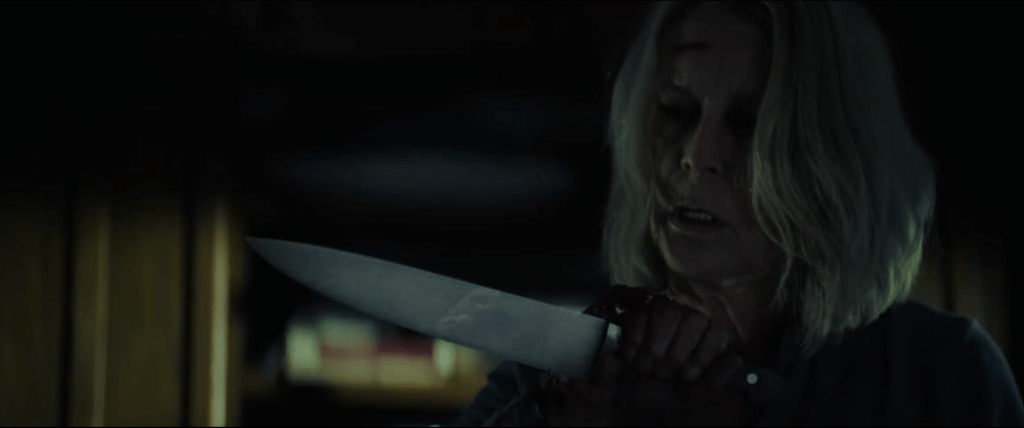

Halloween Ends .. At last.

What is it about?

It doesn’t matter. Oh, it isn’t a Michael Myers Movie!

What is it really about?

Finally, a completely superfluous trilogy comes to an end. What could we not have had instead of this trilogy?