What is it about?

A TV series reveals more about a boy’s identity than he can bear.

What is it really about?

Oops, it’s not just the TV that’s glowing. Your eyes are glowing too. Your nerves are glowing. Something is glowing that dazzles and offers a coziness in the blinding light that is all too easy to snuggle into while slowly going crazy.

The body before the glow

The weekend morning program on TV in the 90s enveloped my childhood bedroom in an amorphous meadow in which I rolled around week after week. The blades of grass of the flickering red, yellow and blue pixels of my tube TV oscillated around me so that I was completely immersed in it. In addition to cartoon series such as The Simpsons, Ren & Stimpy, Rocko’s Modern Life, Hey Arnold, Aaaahh Monsters!, I was telemedially socialized by series such as Pete & Pete, Parker Lewis, Goosebumps, Kablaaam!, The Dinos and Clarissa Explains It All. This often very anarchistic, colorful excessiveness of the morning program was supplemented in the evenings by the vampiresque adventures of the series Buffy or the terribly strange horror stories of Mulder and Scully in The X-Files, as well as the curious journeys to the Outer Limits or the relaunched Twilight Zones.

The commercial breaks between shows were never skipped, but lit up my poster-covered nursery as frenetic overtures thanks to their memorable jingles and super-awesome toy endorsements. Back then, when I was 1.20 m tall, only jumped around in XXL shirts, wore shoulder-length hair and chipped my front tooth while skateboarding, when I wasn’t playing basketball like Michael Jordan or Denis Roman or shooting friends with red turtle shells in Super Mario Kart. But time and time again, my boyish flesh sat hallucinating in front of the flicker box and let the colorful rush of images drive me out of reality day after day.

The glow

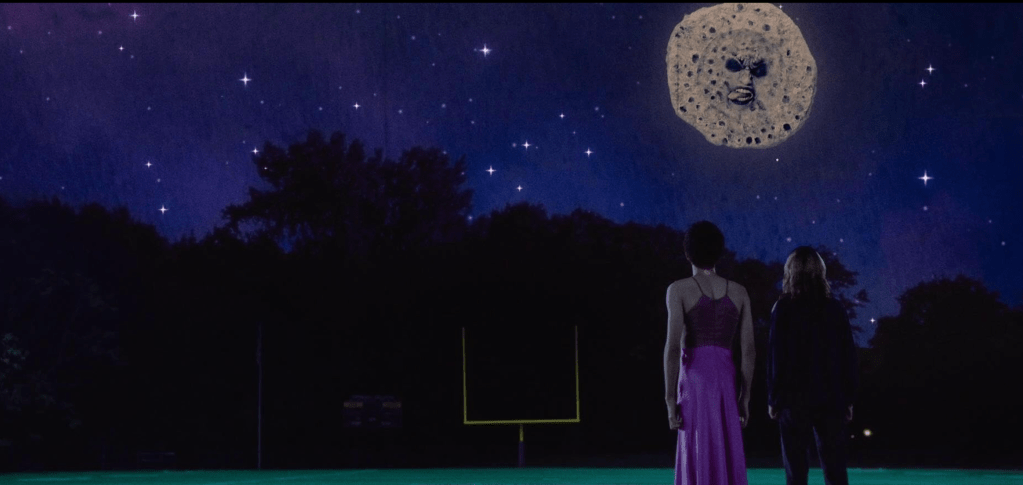

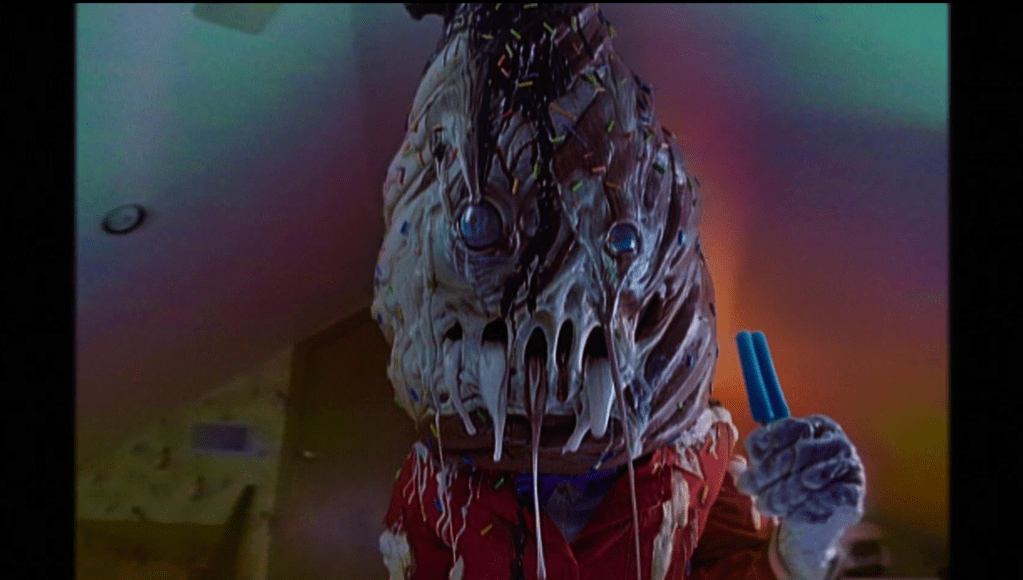

I Saw The TV Glow throws us as viewers right into that time. A time when it was essential not to miss an episode of your favorite series because there was simply no opportunity (or prospect) of ever being able to watch it again. The pre-pubescent Owen loses himself with an older classmate in the teen series called “The Pink Opague”. The series is about two teenage girls telepathically interacting with each other to fight the monsters sent to them week after week by the chief villain Mr. Melancholy. Owen and Maddie watch the series for five seasons (although Owen only watches it in secret because his parents forbid him to do so). Then, surprisingly, the show is canceled with a tragic ending in which Mr. Melancholy wins over the girls, rips out their hearts and leaves them to die in the Midnight Realm. When the series finale airs, Maddie also disappears, leaving behind only a burnt-out television and Owen, who does not want to flee the small town with her.

Many years later, Maddie unexpectedly reappears in Owen’s dreary and miserable life and tells him about her turbulent life, culminating in her having herself buried alive so that she can live in the world of “The Pink Opague”, where she lives on as one of the protagonists in a sixth season. By telling her life story, she reveals more to the inhibited and intimidated Owen than he wants to know about himself. She questions his connection to reality and whether he really remembers the film evenings together as accurately as they took place or whether he has not rather internalized them as a fictionalized memory narrative about the series “The Pink Opague” as a projection screen. Images of him in a woman’s dress in the style of the TV show are faded in at the moment of the confrontation, further images of him merging with the female main character of the series. Maddie offers him the opportunity to say goodbye to this world, which he interprets as reality, and to destroy his ego from this illusory reality in order to finally reincarnate in the real world, namely that of the “The Pink Opaque”.

Owen himself is presented throughout the film as a withdrawn and introverted person. His aura is entirely taken up by poetry-less melancholy and grave-voiced apathy; there is never an emotional movement to be discovered in his facial expressions, apart from a bashful twitching of the corner of his mouth when he wears the dress. His sexuality remains ambiguous, if not non-existent, for large parts of the film. When asked whether he likes women or men, he replies indecisively with “I like series”. In this central, harrowing re-encounter with Maddie, the central conflict within him is revealed: Just as Maddie could not find her way in the heteronormative world and even fled from it, Owen, however, is still stuck in this repressive world for his nature, in which he continues to find himself uncomfortable in his boyish body. She tries to convince him to leave this imposed, dysfunctional world, to bury his old, masculine self in order to live on as the person he had projected through the series “The Pink Opague”, namely in the main female character Isabel.

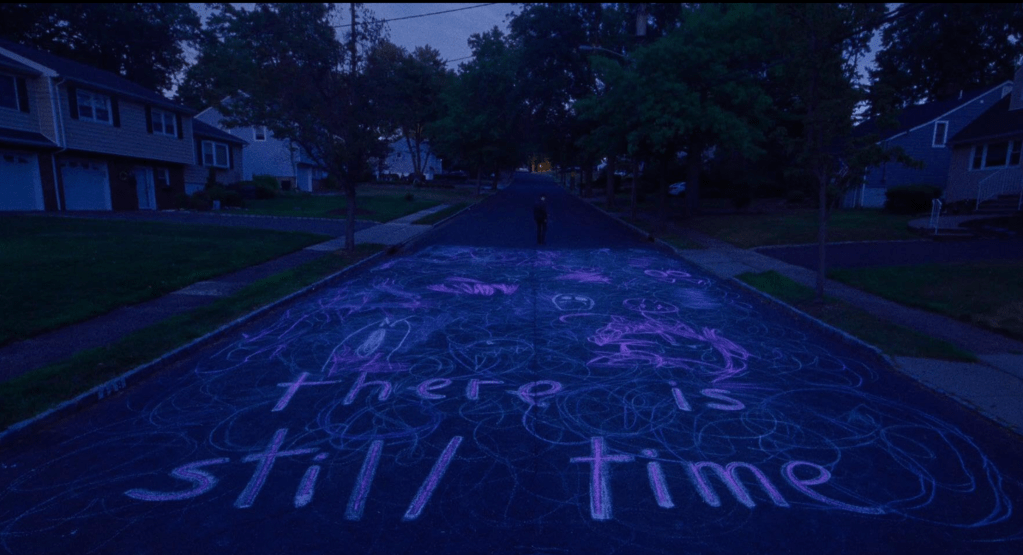

The glow of television (and The Pink Opague in particular) thus represented a portal to self-discovery for Owen in childhood and became an oppressive force as he grew older, reflecting his retreat into repression and social conformity. In the midst of this incandescence – in this escapist shelter – lies Owen’s true identity, dwelling in electronic flashes between transistors and line transformers that constantly reveal the spark of potential to reclaim his identity (“There Is Still Time”).

The body without glow

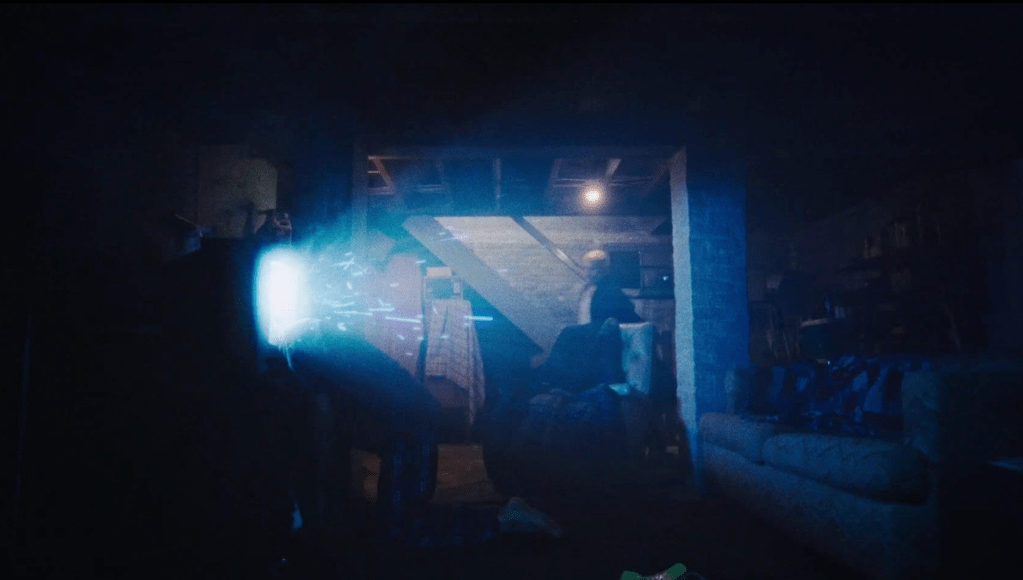

The rough summary already makes it clear that I Saw The TV Glow is not an easy movie to enjoy on a Sunday afternoon. I Saw The TV Glow demands a lot from the viewer, both thematically and in terms of staging, even if it occasionally tickles the viewer with belly-brushing nostalgia. Not only is the film clogged with multi-layered symbols that need to be deciphered, it is also shrouded in a gloomy fog of melancholy and depression, a twilight, ghostly state that is complemented by a washed-out image and camp 90s VHS aesthetic. Despite minor nostalgic Buffy reminiscences, there’s no sunshine and candy here, but pure human suffering. The intense scenes drip with soul-baring, melancholy suffering full of existential problems, domestic violence and social repression, in which the (symbolic) death of the self ultimately feels more like redemption.

To make matters worse, however, the formalistic orientation of the film shows figures but no characters. Throughout the entire running time, the characters’ personalities are never fully explained to the regular viewer; in their ambivalent, elliptical portrayal, they are more like figurative blueprints into which the viewer can empathize and sympathize with the characters’ emotional states and situations. Provided, however, that they can. Otherwise, the figures are not completed characters, but inadequately projected shells.

Through the personal past of non-binary transperson Jane Schoenbrun (director and screenwriter), the discovery of gender identity is treated allegorically through the characters of Owen and Maddie, but – wisely – without spelling it out with hammer-smashing clarity. Instead, Schoenbrun sends us through a neon-drenched dream environment in which dark reality and even more monstrous fiction blur for us, just as the construct of binary gender loses its distinguishable edges, falls apart in cracks and is transformed into a dense fluid.

Since I didn’t question my gender identity in puberty (or had to question it out of an inner feeling), my biggest problem is definitely, unfortunately, not being able to find any personal points of connection to the schematic characters in order to fully empathize with their conflicts; it would probably be different if they were defined characters I could empathize with. In I Saw The TV Glow, therefore, I have to watch two characters that I can relate to but rarely empathize with (and in particular Justice Smith as Owen, whose wooden, flat acting repeatedly knocked me out of immersion). As a result, I can enjoy the movie intellectually but not emotionally to its fullest. The consistently depressing moods are difficult for me to grasp; especially in the episode when Maddie returns, should have found herself, but still seems miserably depressed. However, I was overwhelmed with enthusiasm in every scene of “The Pink Opague”; especially the staging of the terrifyingly dark, haunting series finale.

The body in a disembodied glow

I deeply regret the fact that I was denied access, because the film has incredible potential that will keep many generations busy exploring. In any case, through Reddit and Letterboxd, I have the feeling that younger Gen Z in particular have a more natural approach to the movie. Perhaps it has something to do with the fact that I grew up in a different environment in terms of identification through the presentation of the body and physical representation of identity in the age of the internet. As a young adolescent in the early 2000s, the question of gender identity was hardly ever asked in public. Of course, heterosexuality, homosexuality, bisexuality and transsexuality were accepted in my environment (while the fashionable term of metrosexuality was added in the media), but the discrepancy between biological and social sex (gender) was not discussed in public or even at school.

The fact that the Internet will enable a broader perspective here is exciting because in the worst 56k modem times I remember the Internet as a haven of disembodied voices that communicated with each other worldwide in letters and smileys. You were what you wrote, detached from your body or biological gender, religion, age, everything. With the popularization of social networks (especially MySpace and even more so Facebook) and the publication of images, the body image automatically came to the fore, while the written word, the disembodied voice, faded away. Increasingly, the Internet, which was in itself disembodied, turned into a stage for representative body images, which were increasingly concerned with questions such as “What do I want to show of myself?”, “How do I want to be seen by others?” and “What do I look like in this photo?” in order to participate in socio-collective events. The infinite and invisible eyes on the internet immediately prioritized the body over the voice (as a representative of the soul). As a result, the body became overly important.

Apps such as Tinder reinforced this hyperbolic importance of the body, with only the effect of the body determining the sexual offer. It has probably also changed the way we look at ourselves, because the hyperbolic importance of the body has confronted us with our own bodies more than ever before. In such a setting, we struggle more than ever for autonomy over our bodies. But in its repressive, simple nature, society has an idealistic view of and civilizational expectations of the body. An individual body that deviates from these expectations is at risk of being condemned (even on the internet itself). To make matters worse, the body always goes hand in hand with sexuality, as it attracts and dominates the first glance of desire and reciprocally also makes it clear to us that the shape and form of our own body also regulates access to sex, i.e. enables or even blocks it. However, the increased confrontation with one’s own body that accompanies this also allows it to be experienced more consciously.

Where there is a threat that the flood of images will not only preserve heteronormative gender images, but also infinitely reproduce and ultimately perpetuate them, the spectrum outside the norm can also assert itself and show itself. Through the international, language-barrier-free staging of bodies, it is thus also possible to find one’s buried gender identity in solidarity amidst the colourful array of bodies. Non-binary and trans identities have thus (finally) become more visible and can increasingly be recognized as legitimate forms of expression of individual identity. While such identities were marginalized to the point of complete invisibility and suppression in my youth, they are now experiencing more social (albeit insufficient) acceptance thanks to Gen Z, which grew up with a focus on the physical as a matter of course early on in its heyday. And even if this is still a difficult path for those affected, it is a social enrichment for which I Saw The TV Glow makes an intelligent and creative contribution – even if I find it difficult to access.

Conclusion

Good.

Facts

Original Title

Length

Director

Cast

I Saw The TV Glow

100 Min

Jane Schoenbrun

Justice Smith as Owen

Brigette Lundy-Paine as Maddy

Ian Foreman as Young Owen

Helena Howard as Isabel

Lindsey Jordan as Tara

Danielle Deadwyler as Brenda

Fred Durst as Frank

Conner O’Malley as Dave

Emma Portner as Mr. Melancholy…

Madaline Riley as Polo

Amber Benson as Johnny Link’s Mom

What is Stranger’s Gaze?

The Stranger’s Gaze is a literary fever dream that is sensualized through various media — primarily cinema, which I hold in high esteem. Based on the distinctions between male and female gaze, the focus is shifted through a crack in a destroyed lens, in the hope of obtaining an unaccustomed, a strange gaze.

Leave a comment