What is it about?

A clown – a shadow of ourselves – lives out his sadistic streak to the full on Halloween night.

What is it really about?

I’m late for the party again. But what counts: It happened. I didn’t actually want to. I surrendered. I was watching Terrifier. I feared the worst. I liked it surprisingly well.

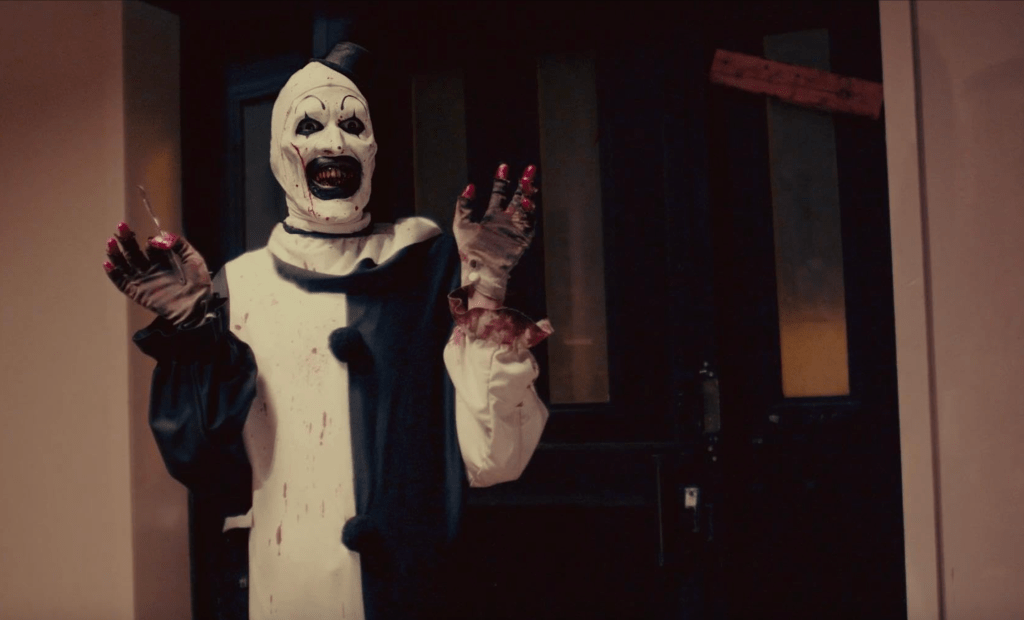

The violence-laden mythos dripping from Terrifier’s reception wrapped itself around my nerves and squeezed out splatter joy. But not only me. With the third orgy of blood, Art the Clown makes his way through the drooling crowds. A murderous clown, then. Hasn’t that been done a hundred times before? Pennywise. The killer clowns from the farthest corner of space. Yes, even the Joker somewhere. Or the cinematographic curiosities of the Insane Clown Posse. So why is Terrifier such a huge success? You don’t have to look at the movie too closely to see the secret recipe (which was certainly put together unconsciously): The excess of the clown portrayal, driven to perfectionism, as well as the boundless excess of splatter. And – let’s not forget – the horror clown panic that scared the bejesus out of innocent home-goers in 2016.

Clowns per se are already predestined to be scary. The clownish mask, along with suggestively presented humor and joy, hides the true face and thus the true self. We do not see the personality, but the persona. A mask that only shows us what we are supposed to see and hides what we are not supposed to see. The true facial expressions of the clowns are never fully legible beneath the make-up and/or mask, and are also reinforced by their silence and covered up with expansive and theatrical gesticulation. Their voluminous red lips look as if they are still covered in the blood of the victims they have torn or as if – due to the emphasis on the lips – they are about to be kissed by a stranger. The blood-red knobbly nose pops out of the pale face like an unnatural deformation. The parabolically drawn eyebrow lines intonate beams of joy and curiosity, but in their rigid sameness mask any absence of negatively connoted but highly human emotions such as doubt and irascibility. True to Mark Fisher, everything about them seems strange, an unnatural modification of humanity that is only accepted because we have been socialized to perceive clowns as harmless klutzes rather than bizarrely costumed adults behaving in an ambiguous travesty of childishness.

Next to them are the aesthetically and elegantly native Harlequins. These color-desaturated clowns with black and white chessboard costumes not only play joyful emotions in pantomime performances, but also the opposite, lateral keyboard of emotions: Namely sadness. They also like to use make-up accents such as the popular tear under one eye. This makes them not only magicians of laughter, but also proclaimers of guilt, as the audience in particular likes to be charged with complicity in the actor’s sadness and forced into action so that the Harlequin’s tears can return to the euphoria-inducing opposite pole. The muteness of the clowns and harlequins in particular requires us to interpret the gestures and mimes instead of reading them. Since every gesture and facial expression is also pure manipulation, expressed solely in order to deliberately demand a reaction from us (by laughing or feeling sorry for the clown), an unparalleled threat lurks unconsciously beneath the make-up, which is further intensified when we become aware that a clown (or harlequin) is blatantly chumming up to us. We are exposed to them and either we laugh along with them or God have mercy on us. Because this ingratiation is bound to an egotistical purpose. But what do these clowns want from us? Is it really just to make us laugh, or are there much more vile thoughts lurking behind these masked countenances, but they never become tangible or perceptible to us because their holistic appearance is permeated by lies and nothing but lies. This is exactly where we come to Terrifier or Art der Clown.

Clowns (like Art) also represent an archetypal embodiment of the trickster, whose chaotic, infantile and often ambivalent habitus violates general rules and social norms and resolves this with ironic and surprising actions. C. G. Jung writes: “The trickster is a figure that emerges from the primitive background of the collective unconscious. He is a fighter, a seducer and a cunning deceiver.” The clown as trickster can therefore be assigned to the shadow archetype, a dark side of the self described by Jung. The shadow stands for suppressed and unconscious parts of the personality, which often contain morally reprehensible or socially unacceptable characteristics. Clowns, as figures who flout the rules and act in crazy ways, often embody precisely this shadow of the collective unconscious. The shadow here is the negative of the persona, i.e. the mask that he himself displays and which stands for our own normative masks that we put on every day and which – according to C. G. Jung – helps us as “individuals to present ourselves in the world, but which often has little to do with the inner self”. As a result, the shadow of the clown, his charged urge to create chaos, mirrors the unconsciously lurking urge within ourselves.

Art the Clown embodies the art of being a clown like no other. In a five-minute scene at the beginning of the film (which unfortunately receives far too little attention), his monstrous strangeness and thus the monstrous strangeness of clowns themselves is staged in the most uncomfortable way possible: He strides into a pizza store, his heavy garbage bag slung over his shoulder. His gaze is fixed on the main character, Tara, as if he could look directly through her eyes into her body of flesh. He sits down at the table next to her and continues his creepy stare, ignoring everyone around him as if they were just smoke and mirrors, until he finally loosens his predatory fixation and beams up to both ears. But his clownish, joyful smile remains fixed on Tara like an awkward man who doesn’t know how to approach the object of his desire. Tara, however, is at the mercy of his intrusive gaze, because while he is masked, she is unmasked. Compared to him as a clown, every emotion can be read from her facial expressions and gestures. She feels completely naked in his superior presence, flayed to the flesh, her vulnerability already torn from her throat and exposed. When he slips a ring from the gumball machine over her finger, her fate is determined. She is at his mercy until death do them part. This demonic creature will not allow a divorce. Because he appears threatening throughout this scene, although he does not directly threaten anyone, but – on the contrary – rather suggests attention and joy and even love, it becomes clear to us that this will not have a good ending (or a good slasher ending).

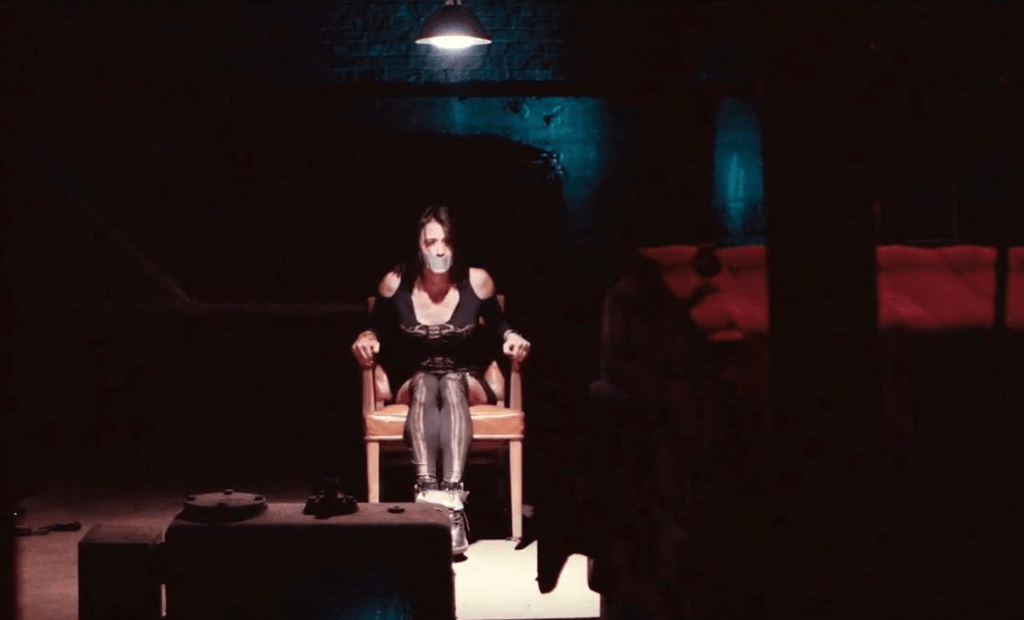

Behind Art’s shadow, a grotesque fantasy of violence manifests itself in unbelievably perverted destructiveness. The brutality with which Art massacres his victims is not entirely new or particularly cruel for the slasher genre. The main reason for the brutality here is, on the one hand, the astonishingly neat effects and, on the other, the lechery with which these are indulged to satisfy a lust for the spectator, who delights above all in the prolonged, particularly torturous execution of women with unparalleled sadism: one woman is hung upside down naked with her legs spread apart and sawn up by hand from the vagina to the head. Another woman’s breasts are cut off, which Art then puts on like a brassiere. Before that, he tortures her by keeping her “child” (a doll that the woman thinks is her child) with him and thus maltreating her worried motherly feelings. He eats off another woman’s face until the beautiful woman is left with a disfigured grimace.

Art is also deadly towards men, but not with the same joy of killing as he is towards women. He only kills Tara – the object of his original joy – with a rather emotionless shot to the head, and even though he empties an entire magazine in her face afterwards, it seems less lustful than with the other women, but rather personally hurt and resigned to her rejection. Since the violence against women primarily amounts to the mutilation of sexual characteristics, this is remarkable because Art otherwise shows no sexual desire towards the women, but only the destruction of those sexual characteristics themselves. As he acts in a highly infantile, prepubertal manner, this sexual desire cannot blossom directly as Eros, but can only lead to Thanatos, the death instinct. By merging the sexuality of his victims with death in the brutalities, Art presents the female body as an object for the embodiment of evil and violence itself, whereby the female body becomes the stage on which the destructive side of sexuality unfolds. By mutilating women’s bodies in a drastic manner, Art attempts to gain control and power over the feminine, because he has no other option over his childishly functioning (i.e. impotent) male figure.

With the drastically transgressive performance of Art der Clowns and its diegetic function of representing both the persona and the shadow of the collective unconscious, the audience achieves a catharsis together with their ambivalence of their own persona and shadow. Young women re-experience being at the mercy of these sadistic male gestures, just as men believe they have regained both the superiority and impotence of their patriarchy. Animus can remain animus; anima remains anima. Together they wander through an opaque vaulted cellar littered with remnants of days gone by, whose labyrinthine topology resembles not only the unconscious, but the marital wandering of life itself.

Conclusion

Better than expected. But not art at all.

Facts

Original Title

Length

Director

Cast

Terrifier

84 Min

Damien Leone

Jenna Kanell as Tara

Samantha Scaffidi as Victoria

David Howard Thornton as Art the Clown

Catherine Corcoran as Dawn

Pooya Mohseni as Cat Lady

Matt McAllister as Mike the Exterminator

Katie Maguire as Monica Brown

What is Stranger’s Gaze?

The Stranger’s Gaze is a literary fever dream that is sensualized through various media — primarily cinema, which I hold in high esteem. Based on the distinctions between male and female gaze, the focus is shifted through a crack in a destroyed lens, in the hope of obtaining an unaccustomed, a strange gaze.

Leave a comment