What is it about?

A scientist is hired by the US government to produce the atomic bomb. The victory march against the Nazis is to be realized. After the Nazis are defeated, however, there is a new enemy: the communists. Unfortunately, the scientist has a past that the government considers too communist.

What is it really about?

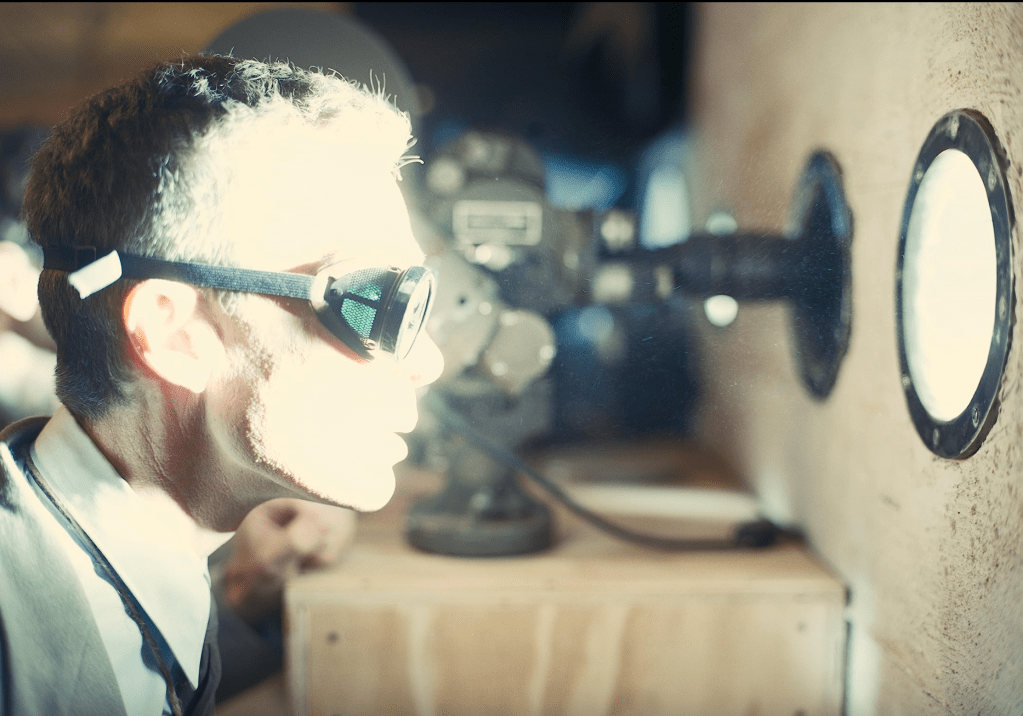

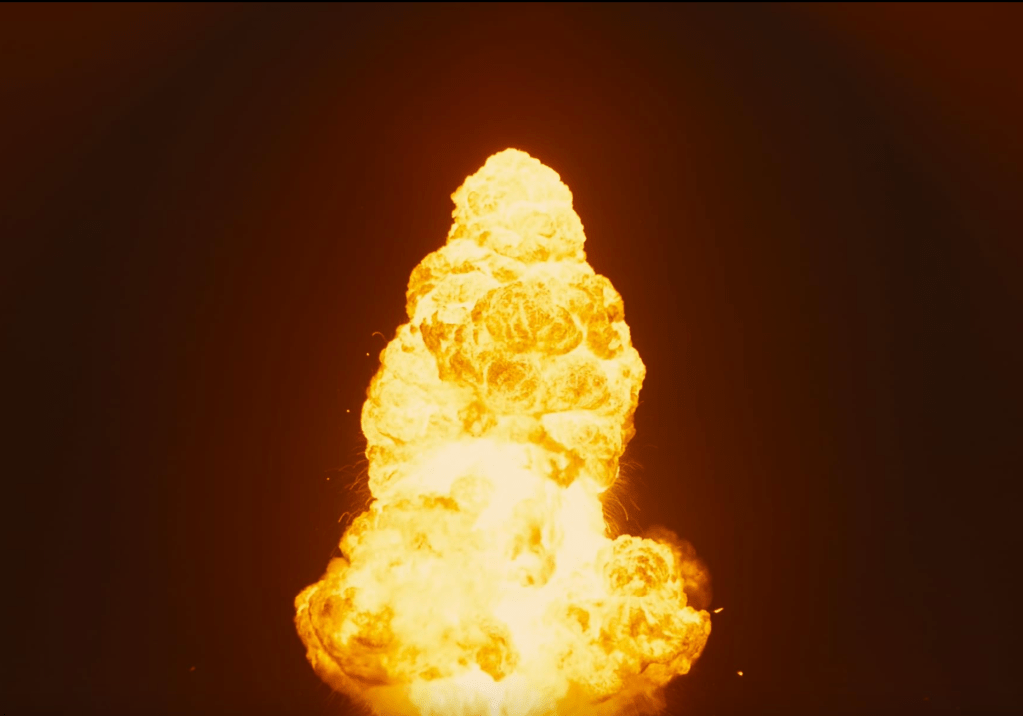

Nolan makes movies. His narrative style is modern, highly industrial, effective. A fusion of pulverized and liquid ideas into a massive, chunky unit, which is compressed in a repeatedly rhythmic pressing hammer until a technically clean, almost flawless work emerges, which, during the quality check, elicits great amazement and murmurs from the engineers with its monolithic creative power; and finally, with the unanimous nod of approval, “Bombastic!”.

Oppenheimer is thus a technically flawless product from Nolan’s creative factory, in which not only Oppenheimer’s private and professional life is told, the research and production of the atomic bomb, the arms race of the USA against the Soviet Union, the political and arbitrary witch hunts for communists on the part of the USA, to which Oppenheimer is soon added; forgetting what he had done for the USA by building bombs, while his own uncritical past – on the fringes of communist-motivated acquaintances and family – will never be forgotten. All the ideas and aspects of Oppenheimer as a person and his dramatic career, as well as the reception of his person and his work, are calculatedly embedded in a story of intrigue against him, which gradually comes to light.

Nolan makes extremely effective use of cinematic narrative techniques in a well-considered and measured manner in order to deal with this mass of content in an exciting way. Thanks to the galloping, timeless editing, the viscerally vibrating sound, the powerful acting, the intimate but also epochal, grand images, a light-footed colossus is created over the enormous running time of three hours, which never, really never, bores at any time. Even with my initial sleepy eyelashes, the movie woke me up from any longing for sleep.

But as apparently perfect as this monolith appears, as a rapturous masterpiece that the world has never seen before, Nolan would not be Nolan if he did not make the same mistakes he has always made – at the latest with the departure of his brother as co-writer: It’s a cold movie by a cold-hearted director. Nolan is an undercooled perfectionist who, in the zeal of his filmmaking, wants to raise storytelling to a new level, and it is this ambition that enables him to capture such narratively flawless films as Oppenheimer on celluloid. His recurring fascinating visions in the eternal duel with the human companion called “time” are, as in Oppenheimer, charming and gripping, told with maximum concentration. But the heart is repeatedly missing.

This makes him very close to Stanley Kubrick, whom I consider to be an equally perfectionist, conceptual person who designed his films on a chessboard or a formula board instead of letting it happen intuitively, like David Lynch, for example. But Kubrick seemed to be aware of the flaw that he didn’t have a knack for emotional characters and thus emotional films; either because he didn’t have the flair or the interest. This is why his characters are predominantly cold-hearted, cynical, violent or perverse; mostly driven by their primal, mostly negatively connoted fantasies. Kubrick’s characters are therefore never shining heroes, but always losers or heroes for whom one would never wish a victory.

But Nolan always tries to tell stories about radiant heroes who often suffer inwardly and who have to fight against the injustice of the world towards them. But by no means does he manage to convey emotion believably because his only tricks of the trade never go beyond pathos and kitsch; be it the awful “love is a force of nature” monologue in Interstellar, the two-sentence rumbling relationship dynamic in Inception or the horribly hackneyed, unspeakably portrayed love story in Tenet. His superficial, purely functional characters act less out of themselves than because the story demands it of them. These characters have no secrets, no passion, no inner life. They only ever present concepts. If the characters are supposed to be sad, then they should cry. If they are supposed to love, then they should kiss. If the characters are supposed to be angry, then they should break something. The production remains superficial, with clichés, with the perspective of an autistic person discussing how fellow human beings express their feelings.

Oppenheimer is no exception. We learn almost nothing about Oppenheimer the man, his ambitions, his inner turmoil, the perspective of his inner life and the denouncing world around him, the strange relationships with women. Instead of characterizing Oppenheimer and exploring him as a person, his life stages are rattled off in a dramaturgically clever arrangement, jumping around in history – oscillating between ascent and apparent descent; ultimately culminating in an unnecessary plot twist that asserts a two-sided rise of a hero of the nation. But the man, his thoughts and his feelings remain largely empty and powerless despite the pitiful attempt. Three hours in and I’m still wondering: who is this man? Why should I know his story? Likewise, the movie completely fails to come to terms with the atomic bombing and the flimsy hounding by politicians. It hawks the misanthropic event as the gesture of an individual and not of a political system.

The movie Oppenheimer is therefore more like an apolitically abridged Wikipedia article whose chapters have been jumbled up and read aloud as a high-quality audiobook that makes your ears prick up. But the movie doesn’t really offer any additional value in terms of contemplation and emotional devotion. Just a dazzled, shoulder-shrugging “Uff … Well, so-so”.

Ergo: Unfortunately, unfortunately, just a product of the Hollywood machine, which naturally shines and impresses at first glance, but on closer inspection has no sensitivity, no engagement, no courage. An over-stylized product without inner life, without character, without sustainability. This is not the heart of a carpenter, but that of a purely materialistic engineer.

I bet that in ten years the movie Oppenheimer will be forgotten, even if it is not formally a catastrophe.

Conclusion

Cold art .. but with a BANG!

Facts

Original Title

Length

Director

Cast

Oppenheimer

181 Min

Christopher Nolan

Cillian Murphy as J. Robert Oppenheimer

Emily Blunt as Kitty Oppenheimer

Matt Damon as Leslie Groves

Robert Downey Jr. as Lewis Strauss

Alden Ehrenreich as Senate Aide

Scott Grimes as Counsel

Jason Clarke as Roger Robb

Kurt Koehler as Thomas Morgan

Tony Goldwyn as Gordon Gray

John Gowans as Ward Evans

What is Stranger’s Gaze?

The Stranger’s Gaze is a literary fever dream that is sensualized through various media — primarily cinema, which I hold in high esteem. Based on the distinctions between male and female gaze, the focus is shifted through a crack in a destroyed lens, in the hope of obtaining an unaccustomed, a strange gaze.

Leave a comment