What is it about?

Godard, who talks for over four hours about the history of cinema, about stories of cinema, about his own history with cinema.

What is it really about?

Histoire(s) du cinéma.

Histoire(s) du cinémoi.

History(s) of cinema.

His story(s) of cinema.

Looking at a canvas is like looking into the head of a stranger. Thought-transformed images and sounds, once sprung from the big bang of thought, which falls letter by letter into the hands of the creator and is incubated with body heat until it hatches as a word and is given birth in the clattering beat of the typewriter, that word machine which immortalizes thought and which swivels its head horizontally from left to right. In front of this mechanical apparatus a brittle voice rises, it tones, over which the typewriter clacks like a machine gun, but otherwise remains silent.

“Let each eye negotiate for itself. Do not uncover all sides of things. Keep a margin of indeterminacy.”

The fading thought that returns on paper, made immortal. And what is immortalized on paper can be revived on canvas, that projection surface which in the light bulb coaxes the thought out of the darkness, as it was equally translated from the dark, foggy thicket of the thinker’s bulb onto white paper to the world. What is revived on screen is not just entertaining flickering, it is the memory of modernity. It is a think tank and memorial about the history and stories of the 21st century. That of cinema.

About this Godards succeeds in his cinematographic essay “Histoire(s) du cinéma”. In four double episodes. Total running time: 4.5 hours. Produced for French television between 1989 and 1998. Fast forward to the then groundbreaking medium of video, which made it possible in a simple way to preserve, re-cut, recontextualize the heavy celluloid compactly in cassette form. The playground of Godard, who amassed a personal archive from whose smorgasbord he now tells the story(s) of cinema. No, this is not lexical infotainment as one would expect on Netflix. Not the multiplication tables of the film lesson, to be treated factually and eye-opening with a clipboard and freshly sharpened pencil, as once Every Frame is a Painting. Instead, Godard sits in front of the camera and behind the players to stuff the viewer again and again with sweet as well as salty popcorn until it sticks in the throat (optional: in the nose) and cheese sauce runs here and there like tears from the eyes.

Sure, Godard has since the end of the 60s anyway quite a screw loose and turns since then his own thing, of which actually no one really gets what he is shooting; the one of it annoyed, the other is fascinated by it. It’s not much different with Histoire(s), as Godard maneuvers his story(s) extremely cryptically by means of text insertions and voice-overs along a slithering red thread, condensing the presentation through the so-called story(s) with countless film excerpts, pieces of music, quotations from literature, philosophy and paintings from the visual arts. Not only does film history per se play the supporting role, but Godard interweaves his narrative into at least the following levels:

(a) The film history. Beginning in the bosom of the Lumiére brothers, with whom cinema learned to walk, via Eisenstein and Griffith, with whom it learned to speak (in film), via Hitchcock, Hawks and Ford, where it came of age, to the end of cinema, after it lost its innocence – above all through the Holocaust and its treatment of cinema (both documentary and fictionalized) – and is thrown to Mammon, reinforced by American cultural imperialism.

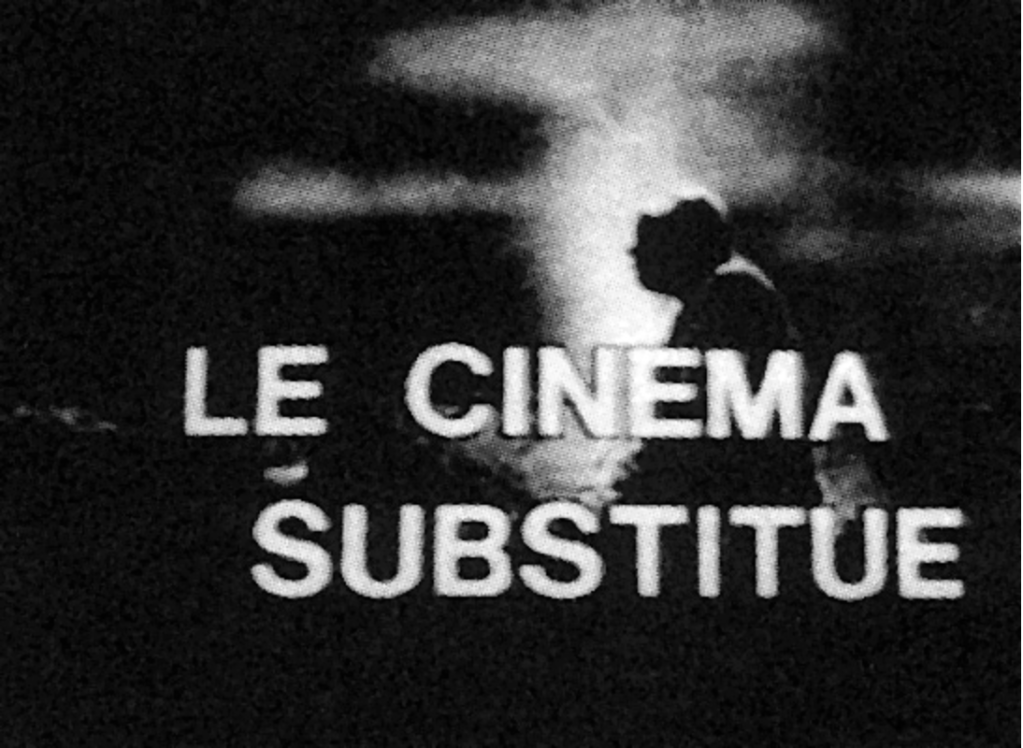

(b) The real human history of the 21st century, packed with (world) wars, genocides, revolutions, political and social upheavals, new discoveries, inventions. The history of a century captured (documentary) and retold (fictionalization) with the gaze of the medium of film.

(c) The fictional stories told in film. In short, the stories that are not based on true events in human history. Stories that provide escapism from reality (fantasy), muddle psychotraumatic (crime, horror), and/or psychosexual stimuli (porn).

(d) Backstories of films. About the making of a film, the shooting, the post-production, the reception.

(e) Godard’s own cinephile biographical history. From a film critic to an initially highly decorated to later for the general completely forgotten auteur filmmaker.

These are the story(s) that the Histoire(s) du Cinéma, to which Godard devotes himself in this impressive and most important work: “A story that had been enumerated but never told.”

Stories that in Godard’s hands and quote ecstasy an electrifying and dreamy meme fireworks, a celestial glow, melted into those five levels of meaning, which, however, never light up separately from each other, but simultaneously, overlapping in seconds, reflecting each other, as a kind of intercommunicating levels of meaning, in which the cinema spirit chats and brings light into the darkness. At least Godard’s cinema spirit, which haunted his head crosswise. All five levels of consciousness are therefore not juxtaposed in parallel or even hierarchically nested, but rhizomatically intergrown/nested, at the same time feeding off each other, perpetually blurring and colorfully intermingling in chains of associations and cross-fades; simply levels of consciousness that speak to each other in echoes, even if they never understand each other. The spirit of cinema and its story(s), in which the gassed, emaciated corpses of the Holocaust make an appearance with the Marlboro Man and are counter-cut a little later in close-up of a vaginal penetration and the wildly laughing Pinhead Pip from Freaks.

It is the cinematographic equivalent of James Joyce’s belletristic word pusher “Finnegan’s Wake,” a highly complex monumental work peppered with neologisms and (foreign) wordplay, which is worked through word by word (in Godard’s case, image by image) and which likewise masters multiple levels of narration/consciousness by means of the language of the textual medium, articulating cultural as well as socio-political history in equal measure. Both works travel the walls of the nature of their arts and form a boundless experience in the recipient.

Histoire(s) du Cinéma is therefore a synapse blaster. Through montage and collage, the history(s) of cinema are transformed into a complex network of images, sounds, and quotations. It is as if one were in a panopticon, looking through a telescope that Godard constantly jiggles.

The episodes themselves are thematically subdivided, with this family inheritance intertwined with each other in chronology. For in the progression of the series, the births of the individual episodes, the genetic reference to the ancestors, the previous episodes, is taken up again and again:

(1a) Toutes les Histoires – – All the Stories: A look at the earliest childhood of cinema, which evolved from crawling to walking upright with the help of technological progressivity. At a time when cinema itself was seen as the heir to the visual arts and photography, while recognizing their cultural upheaval: In Hollywood as a dream factory and in the Soviet Union as a myth factory.

(1b) Une Histoire Seule – – One Story Alone: Cinema as a unified narrative, in which two handfuls of basic plots vary into genre-typical narratives and also evolve in tempo and showmanship, but are in principle locked into the same structure. It is also colored by film-theoretical and film-critical arguments that examine the medium with a dissecting knife and sketch it anatomically.

(2a) Seul Le Cinéma – – The Cinema Alone: This is accompanied by the question of whether the cinema is an independent art form at all or merely the extended arm of the visual arts, theater, literature, and music. On the other hand, it is also the shadow and light of contemporary events and the zeitgeist, with which it celebrates an unprecedented couple dance (keyword: documentary).

(2b) Fatale Beauté – – Fatal Beauty: The cinema as a place of seduction, where beauty and death can be fantasized at the same time (predominantly by men), above all in the being of the femme fatale. Images and sounds that are there to arouse emotions – both pleasurable and frightening.

(3a) La Monnaie de L’Absolu – – The Coin of the Absolute: One of the central and most understandable arguments within the Histoire(s). About in which reproduction quality the cinema confronts itself with the history and the present and in Godard’s conclusion the impotence of the cinema by the negligent, slightly resistant examination of the 2nd World War and above all the Holocaust – the (horror) event of the 21st century. Only Italian neo-realism was able to faithfully marry history and film and to tell it away with a militant revolutionary spirit.

(3b) Une Vague Nouvelle – – The New Wave: the most self-referential treatise, autobiographical remarks on his old gang. The Nouvelle Vague and its successes and failures for film history. In retrospect, the disillusioned struggle of some young men socialized by American detective story.

(4a) Le Contrôle de L’Universe – – The Control of the Universe: The Medium of Film as a Control Organ of Political State Organs. An ideal instrument for manipulating the masses using the example of the French Algerian War.

(4b) Les Signes Parmi Nous – – The Signs Among Us: Lastly, film is interpreted as an orchestration of (semantic) signs, even as a sign itself and not – like other media – as a command; a sign that one interprets, plays with, lives with. Cinema is the incomparable, powerful memory.

Conclusion

A must see.

Facts

Original Title

Length

Director

Cast

Histoire(s) du cinéma

466 Min

Jean-Luc Godard

–

What is Stranger’s Gaze?

The Stranger’s Gaze is a literary fever dream that is sensualized through various media — primarily cinema, which I hold in high esteem. Based on the distinctions between male and female gaze, the focus is shifted through a crack in a destroyed lens, in the hope of obtaining an unaccustomed, a strange gaze.

Leave a comment