What it is about?

It’s Halloween. Once again. Michael Myers is back. Once again. But this time it’s different. Or not.

What is it really about?

Mikey-boy is back! Finally! For 40 years he has been searching the woodchip wallpaper in an insane asylum for funny figurines, after he – not quite so gloriously – sent three people to the afterlife in 1978. It can happen. Not his best day, admittedly, but as his psychiatrist Dr. Loomis says, Mikey-boy is a bad boy and bad boys do bad things. Prove me wrong.

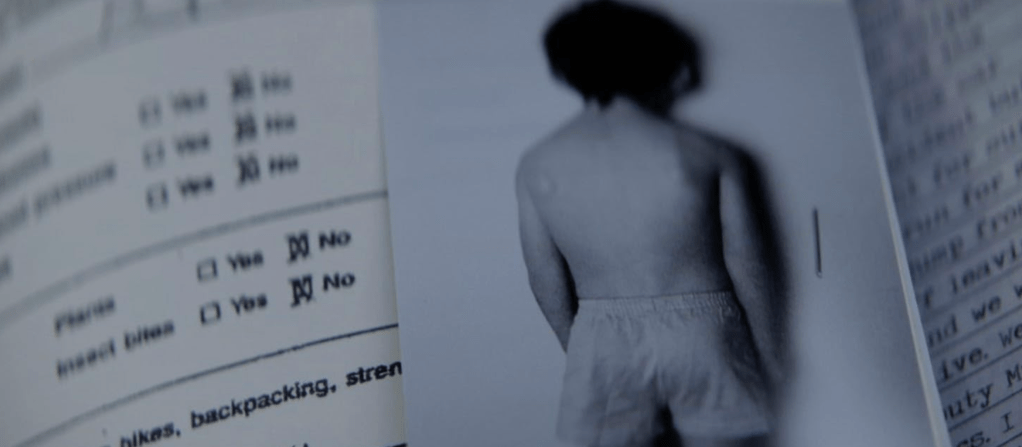

Anyway, he is back now. The crowd cheers, the knives are sharpened and at worst the popcorn gets stuck in your throat in shock before Mikey-boy plunges the knife into your neck. Actually, he had a cozy Halloween ahead of him in 2018, the classic trick-or-treat bash, but it didn’t turn out that way, because one day before the ghost test, two podcasters swooped in and had to get him all fuzzy. They held up to him the dearly beloved William Shatner mask that he used to go on murder sprees with so beautifully. But while he didn’t wrinkle his nose once, his moronic fellow inmates kicked and hooted and yelped and mewed in the most crazy way. What a commotion it was, how annoying and unnecessary. Like something out of a bad movie, a bad, unimaginative script crammed onto the screen, showing the most clichéd portrayal of mentally ill people. Bad, so the viewer – before he leaves the cinema now – is quickly reconciled by the Halloween writing being faded in, the fiddles wailing away, and the frantic synth patter buxing the pulse with joy and with fear to immeasurable levels. The opening credits are the first small highlight for me.

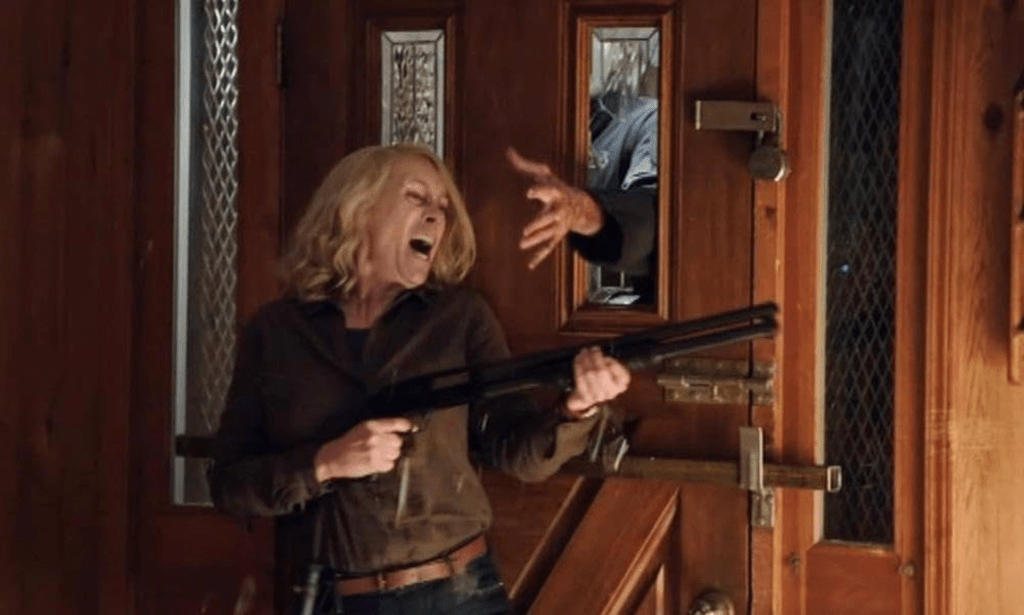

Then they try to tell something like a story. Something about the True Crime podcasters, who I couldn’t care less about; something about Laurie Strode, who escaped from Mikey-boy back in 1978 and is now a super tough, super armed, super paranoid bad ass bitch, in front of whom even John Rambo gets raisin nuts and who is important for the film, so that the old Mikey-boy fans ram into the cinema; then there’s something about her daughter Karen, who also only found her way into the film because she’s Laurie’s daughter and has absolutely no right to exist in this film at all; and then there’s something about her daughter Allyson, Laurie’s granddaughter, who with her teenage years appeals exactly to the target group that is also in their teenage years and has possibly never seen or heard of Mikey-boy. But that doesn’t matter for this “sequel”.

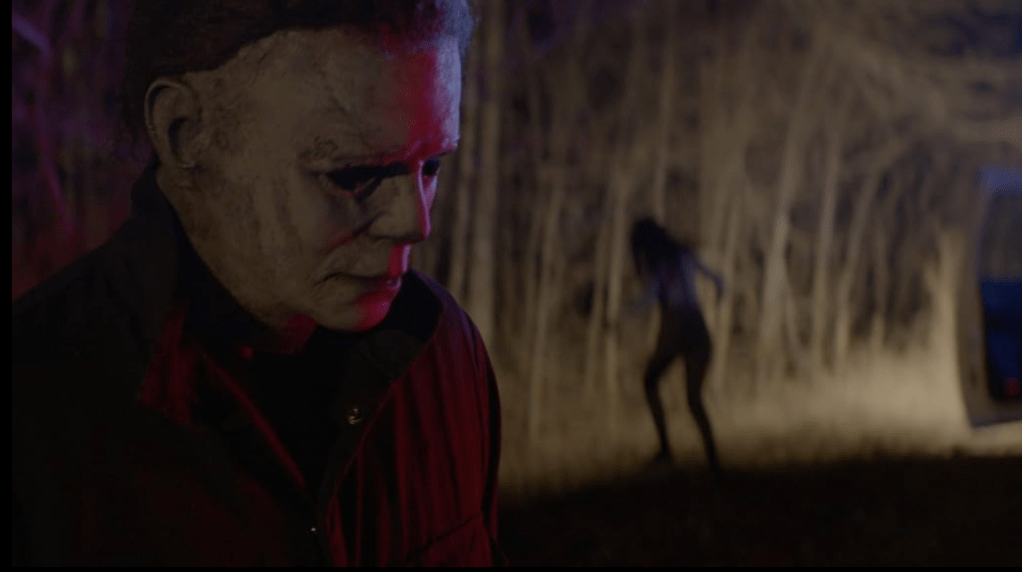

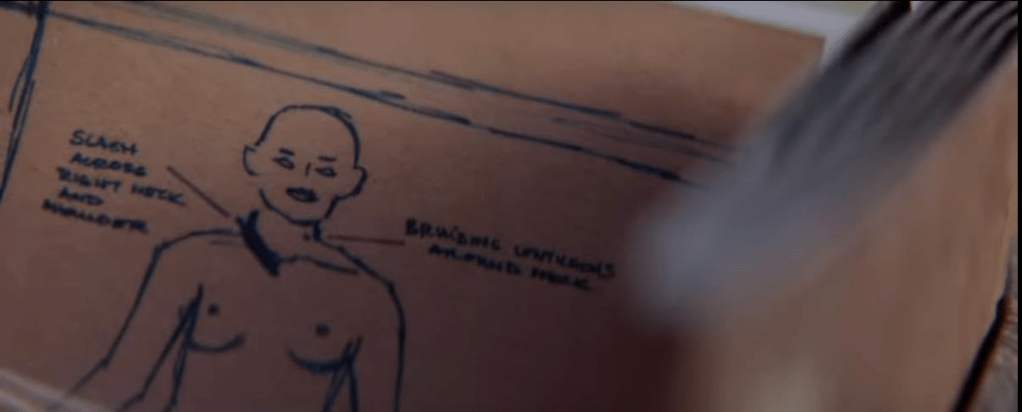

The 2018 film has little in common with the original from 1978. With the exception of the mask and that the perpetrator is called Mikey-boy and one of the hunted Laurie. In his 20s, back in 1978, Mikey-boy was a rather stoic, latently perverted fellow who stalked his victims in best voyeur manner, tracing them mousy-mouthed and eliciting a pleasurable look of discovery while stabbing his victims, quite like a childlike fascination; as if it satisfied him, the psychologically castrated one. In 2018’s Halloween, on the other hand, he’s a badass Terminator who lets nothing and no one stop him, ramming his 40 years of pent-up rage into the inferior bodies, no fascination left to elicit from them but pure murderous lust. He seems to be less a retelling of the child in the hunk’s body than more of that “absolute evil” myth that only all the films have made him into, which here in the 2018 sequel play no role at all, but so really no role at all. Allegedly. In vain. Of course, the ignored sequels also play into this film, as fan service soup, as the hinterland of the unconscious.

The richly anemic but incredibly thrilling original, which robbed the viewer of fear and terror through the sexually subversive poking and prolonged tension to the extreme, can no longer be reproduced in 2018. But it doesn’t have to. The 2018 film does not come close to the original, but can entertain with its audiovisually atmospheric staging as a slasher. Of particular positive note here are actually the teenagers, all of whom are extremely likable, even if some of them are only seen briefly. I liked just about every scene with them. To my mind, a straight slasher with only teens would have been much more intriguing, gripping as well as less picked apart and forced than with the unnecessary referent named Laurie and her daughter Karen. That the violence screw was neatly tightened and adapted to the viewing habits of the 21st century fits for me – even if I regret a little that Michael has lost his juvenile fascination for the dead as a substitute for his own chaste sexuality and virtually only kills in quickies to get to the climax quickly. In general, the subtext seems to be completely abandoned or to flourish solely in preaching “family is everything”. In the end, it’s a Disney movie with blood splatter after all.

Oh yeah, what else is there? A plot twist you can smell pretty early on, and even with exposure it stinks just as your nose predicted it would.

And lastly: What do I actually think of Halloween movies in general? I’ll put it another way: Mikey-boy could never thrill me as a slasher master the way Freddy, Jason or Chucky did. But that’s probably also because parts 4-6, H20 and Resurrection are fucking grotty cucumbers. Rob Zombie’s reinterpretation, however, I thought was successful, even if not as masterful and subtle as the original, but at least something entirely new was tried that can’t be attributed to the 2018. This relies heavily on its fan service and higher quality production.

On a side note: My theory, by the way, is that Mikey-boy only kills on Halloween because he’s a Jeck at heart, a carnival guy. He’d rather be laughing, slapping his neighbor’s thighs with laughter, than stabbing and punching, but Halloween, which is all about fright and fear, tempts him to cause fright and fear himself.

Conclusion

Boooooooooooooooring.

Facts

Original Title

Length

Director

Cast

Halloween

106 Min

David Gordon Green

Jamie Lee Curtis as Laurie Strode

Judy Greer as Karen

Andi Matichak as Allyson

James Jude Courtney as The Shape

Nick Castle as The Shape

Haluk Bilginer as Dr. Sartain

Will Patton as Officer Hawkins

What is Stranger’s Gaze?

The Stranger’s Gaze is a literary fever dream that is sensualized through various media — primarily cinema, which I hold in high esteem. Based on the distinctions between male and female gaze, the focus is shifted through a crack in a destroyed lens, in the hope of obtaining an unaccustomed, a strange gaze.