What is it about?

The misery-porn-like film adaptation of the novel of the same name by Joyce Carol Oates about Marilyn Monroe – from the disturbed view of Norma Jeane.

What is it really about?

What is Blonde about?

Put simply, Blonde is another big-screen adaptation of Joyce Carol Oates’ novel of the same name, which in turn is devoted to the life of Norma Jean Baker, or her poster-printed alter ego Marilyn Monroe.

So is it a biopic?

Blonde is many things, but it is by no means a biopic in the usual sense. The stages of life the film stops at in almost hours are presented in an articulated and fictionalized way, beginning with the fatherless childhood in the violent hellfire of the schizophrenic mother, through the humiliating, repeated abuse by lust devils with the lever in power, the many, fruitless marriages, the shameful, blood-sucking abortions, and on and on.

For whom is the film nothing?

Those who expect a historically accurate portrayal of the far too short life of Norma Jane/Marilyn Monroe will be brutally disappointed (by the way, it’s your own fault if you expect such a thing from biopics at all – – life is not a movie); just as those who hope for an ode to the icon Marilyn Monroe.

This is not a romanticized, fan-pleasing interpretation of a public figure (unlike the unspeakable Bohemian Trashsody), nor is it a stodgy, Oscar-cheering carnival parade like Lincoln.

Blonde is different – and that’s what makes it so controversial.

What is Blonde, then?

“Blonde” is rather an associative concatenation of embarrassing life moments of a seemingly radiant icon whose career is revealed and exploited here as a soul-sucking nightmare. “Blonde” at least deals with the charming, glamorous, very self-confident being, what the figure Marilyn Monroe represents in our minds until today. It is rather an examination of the psyche of an unstable woman who, frighteningly enough, ended her life prematurely at the age of 36 (!) through a pill overdose. Anyone who bears this fact in mind cannot take the still existing public image of Marilyn Monroe, as we see her a thousand times in films and on posters, as the self-confident, strong and enviable woman. The myth of Marilyn Monroe is itself a fiction, a narrative that Hollywood has made us believe; that the press has made us believe and – even worse – that Norma Jeane, the real woman behind the costume called Marilyn Monroe, has made us believe.

Marilyn Monroe is an artificial figure for stage lighting. It is not a human being. The human herself is named Norma Jeane. But what do we, who know only the artificial figure, know much about Norma Jean?

Andrew Dominik labors by all sorts of means to deconstruct the myth in challenging ways. He concentrates on capturing the Norma Jeane in “Blonde”, always hidden under the make-up, the graceful gesture, the quick-wittedness, the poster smile and the sequined dresses, who, as if from a prison (her body), witnesses all that happens around her and what in the flash no one perceives as a prison on her.

The camera penetrates through the body shell of Marilyn Monroe and retells the presumed soul life of Norma Jeane. In the film “Blond” we observe the woman known to us as Marilyn Monroe trying out for a casting in a completely insecure and fragile way, this insecure performance does not reproduce the original casting, but only Norma Jeane’s inner life during the casting. Thus, the interior is put on display and not what we already know as a facade; the untidy inner life emerges. In the introspective portrayal, we see what the then Norma Jeane suppressed in the universally beloved role of Marilyn Monroe, but what was rumbling inside her. Thus, in the scenes one never sees the femme fatale-like, witty and self-confident sex bomb Marilyn Monroe, in other words: not the art figure, but the troubled, insecure Norma Jean, the interpretation of the human being behind the art figure, who helplessly witnesses everything in the split body.

Therefore, watching the film under false premises and expecting more of the glamorous life of a Marilyn Monroe inevitably leads to disappointment and anger. This is not a film about Marilyn Monroe. It is an interpretation about the fragile soul life of Norma Jean. To make matters worse, it is not a portrait reflecting the highs and lows of her life, but only the perpetual suffering. It is: The Passion Monroe. Or no, it is: The Passion Jeane.

And does this concept work at all?

Yes and no. The first half hour annoyed me. I found it incredibly exhausting to have to watch the constantly howling and whispering Ana de Armas as Marilyn Monroe and how only bad and repulsive things keep happening to her from all sides. Abuse, repudiation, rape, auto aggression. As a viewer, I screamed at the TV, yelled at it that I understood that she was in a bad way, but that I would like to see something of the Marilyn Monroe that is commonly known from movies and TV. I had to accept, however, that Andrew Dominik does not want exactly that. With the idea to see here really only the interpreted inner life, I could bear the film far more.

Nevertheless, so I find, the eternal suffering carries hardly over the entire running time, because again and again I feel as a spectator nevertheless only half-baked, one-sidedly involved. I can hardly imagine that Norma Jeane was a constantly broken, desperate and unstable woman as she is shown here. For it is also clear from reports that she was extremely well read and therefore had sufficient quick wit to be able to use situations to her advantage; likewise . This aspect of her person emerges only in the smallest moments.

As a result, the constant barrage of agonizing moments without highs and lows becomes a test of patience that offers little new with each successive scene of suffering and narrates each plot in an extremely predictable manner. Furthermore, the film tortures with sometimes flat monologues and dialogues; for example when her mother drives through a fire smoke and comments “I can’t see anything”. There are, unfortunately, countless examples of this, culminating in a brief but absolute low point in the final, in itself splendidly nightmarish third: the encounter with John F. Kennedy.

What I still could never quite come to terms with was the oversized portrayal of her alleged Electra complex, the father complex.

Electra complex?

In “Blonde,” Norma Jeane is psychologized with a hefty load of Daddy-isms. “Daddy,” a big Hollywood producer according to her mother, is the one Norma Jeane takes it all on for. He’s the one she actually wants, to finally have a father. Andrew Dominik supercharges this longing in constantly whispering daddy purrs, in imagined dialogues with her father, who observes, appreciates and also punishes her public image like God the Father. She also addresses her much older husbands as “Daddy,” as if they were the reincarnation of the father (even if these Daddy-names are also just internal processes, they feel very alienating and trying).

Admittedly, it fits into narrative that the woman who longs for her father ends up in the early days of her career with, of all people, two young men who suffer from the fame and violence of their acting fathers – namely Charlie Chaplin Jr. and Edward Robinson Jr. However, while they envy Marilyn for not having a father and thus being free, their approach to her is an attempt to reach the lost father in the young men, as young images of great Hollywood acting fathers.

And certainly Andrew Dominik opens Daddy also only as a metaphor for Hollywood itself to wrap, after all, it is Hollywood in whose patriarchal arms she has gone and suffers nothing but abuse, but prefers this paternalistic abuse than to get no attention from the “father” at all.

How is the play?

After reading praise everywhere about Ana de Armas acting in “Blonde”, I do have a controversial opinion here: I find the mimicry far too theatrical and exaggerated. Not for a second do the eyelashes and corners of the mouth remain still, there is always a lot going on in her face. Too much for my liking. I had the feeling I was watching an actress act.

What makes the film worth seeing?

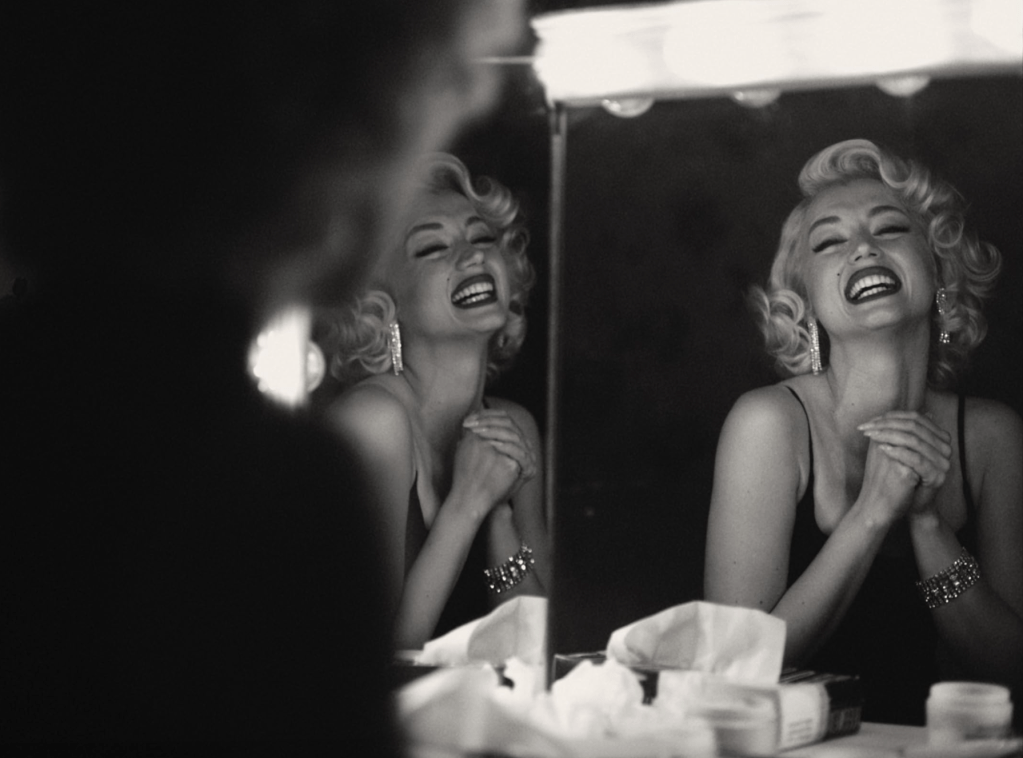

Despite all the criticisms that blow over the film like a storm and which, in my opinion, are mainly due to the partly weak screenplay, one rock remains standing in the surf: The impressive camera, editing, sound and lighting work. “Blonde” is as stunningly aesthetic cinematographically as the myth of Monroe herself. The glamour and turbulence of her life is elaborated through all sorts of cinematic gimmicks: Changing aspect ratios, color and black-and-white imagery, match cuts, out-of-focus, merging bodies, interior body shots. The elegiac soundtrack by Nick Cave & Warren Ellis musically underscores the scenery as a ghost story.

The radical and I would even say: for such a budget experimental staging is reason enough to give the film a chance.

Love it or hate it?

The film is divisive and incredibly stimulating to discussion, not so much about Norma Jane/Marilyn Monroe per se, but rather how she could, should, and ought to be portrayed. I am extremely conflicted. The absorbing production, with few exceptions, took me deep into the abyss of her life, into the psychological terror and nightmare that the real Norma Jeane must have had to endure inwardly and alone at the time, and broke from it – far too soon – while her mythological appearance did not reveal a single worry line or tear. I am therefore also grateful that Andrew Dominik has chosen a different way to interpret Marilyn Monroe.

Conclusion

Neither flop nor top.

Facts

Original Title

Length

Director

Cast

Blonde

167 Min

Andrew Dominik

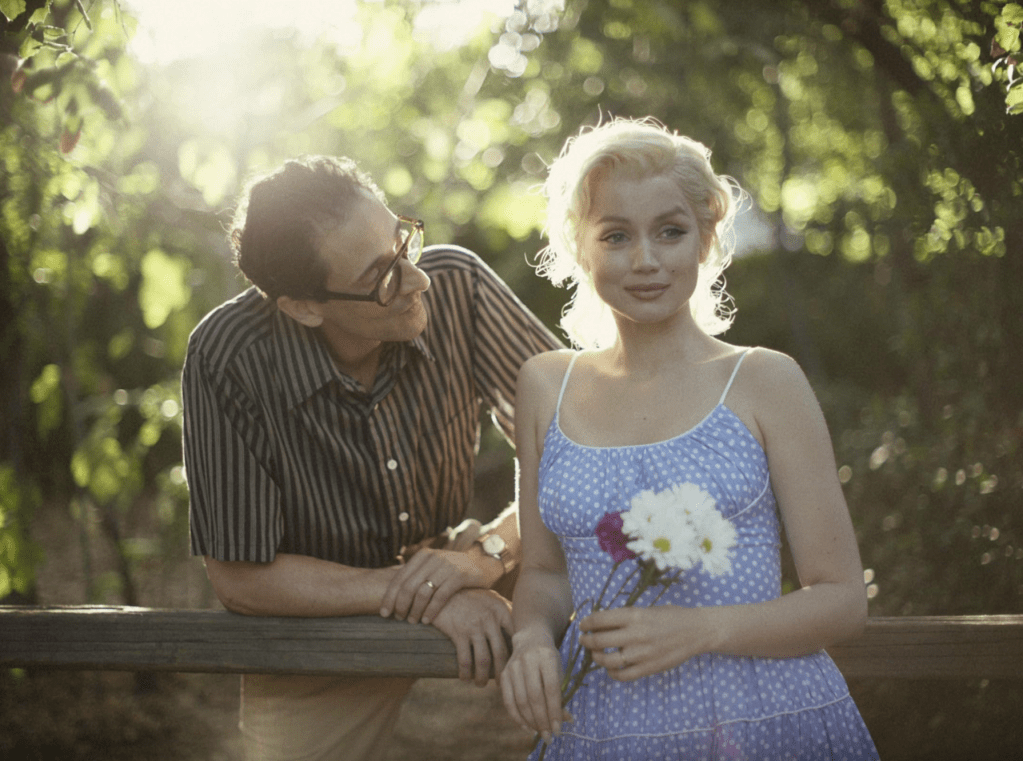

Ana de Armas as Norma Jeane/Marilyn Monroe

Lily Fisher as Child Norma Jeane

Vanessa Lemonides provides Monroe’s singing voice

Adrien Brody as The Playwright, Arthur Miller

Bobby Cannavale as Ex-Athlete, Joe DiMaggio

Xavier Samuel as Cass Chaplin, the son of silent film icon Charlie Chaplin

Julianne Nicholson as Gladys Pearl Baker, Marilyn Monroe’s mentally unstable mother

Evan Williams as Edward “Eddy” G. Robinson Jr.

What is Stranger’s Gaze?

The Stranger’s Gaze is a literary fever dream that is sensualized through various media — primarily cinema, which I hold in high esteem. Based on the distinctions between male and female gaze, the focus is shifted through a crack in a destroyed lens, in the hope of obtaining an unaccustomed, a strange gaze.

Leave a comment