What it is about?

A group of young schoolgirls visit and old lady, her suspicious cat and her murderous haunted house. There they leave puberty behind and grow up … or else they are eaten by a piano.

What is it really about?

Once upon a time there was a Japanese director. His name was Nobuhiko Obayashi and he was also the father of a 10-year-old daughter. One evening, as the cherry blossoms began to sprout from their buds, two men from the Tōhō palace in the big city came to the home of Obayashi and his daughter. Father and daughter gave the rain-soaked men food and drink, and the men reciprocated with great thanks, handing over a heavy sack of golden thalers. “Make us a movie,” the first man said to Obayashi. “A movie like Jaws, and then make this sack of thalers into a truckload of thalers.” The second man gave him another hint, “tapping the thalers three times brings good luck and rain of ideas.”

Even before the sun rose over Mount Fujijama, the men disappeared into the mist. When Obayashi’s daughter awoke from restless sleep, and with honeyed mouth at morning hour she told her father about her strange, even bizarre dreams, the cherry blossoms began to bloom in eye-opening splendor: “Daughter, shake and shake, throw all your ideas over me!” Immediately the ideas gushed out of his daughter, dreamlike tales surging in unfathomable beauty of childlike innocence. Attentively and quite proud of his daughter, he listened to her imaginative tales. With each of her words were painted paintings full of nostalgia, childlike anxiety and carelessness. When the daughter was tired and exhausted from talking non-stop, the father announced on the empty-swept streets, “Such great ideas of his daughter, oh sure, he always shoots something better than Jaws”.

The days passed, the moon patted the sun’s limp shoulders, and as the last cherry blossoms were carried across the land by the wind, the Japanese director, as prompted by the two men, began to make a film called Hausu. About a ghost story that spoke from the pure youthful heart of his daughter. It is about a young sixteen-year-old named Gorgous. Many years ago, her mother was lost. A long-awaited summer vacation with her father is about to begin, to step out of the mountain shadow and climb to the sky-lit top of the world. But surprisingly, her father became involved with another woman; a woman so beautiful and graceful looking that even the mirror on the wall marveled at her brilliance from the fairest in all the land.

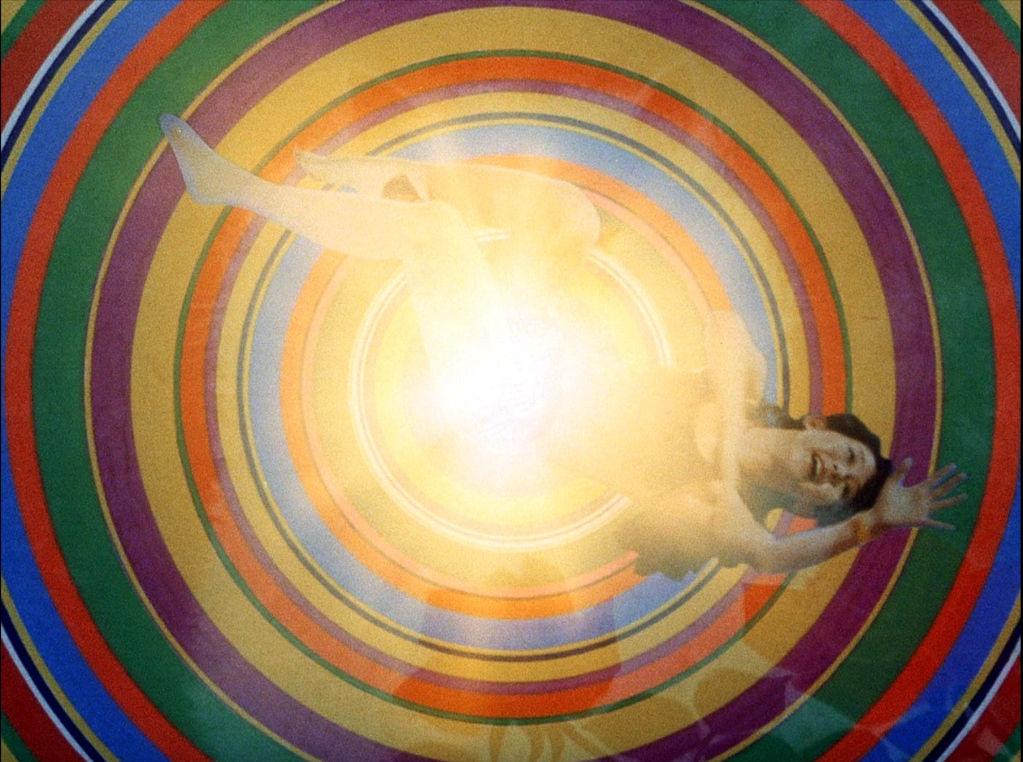

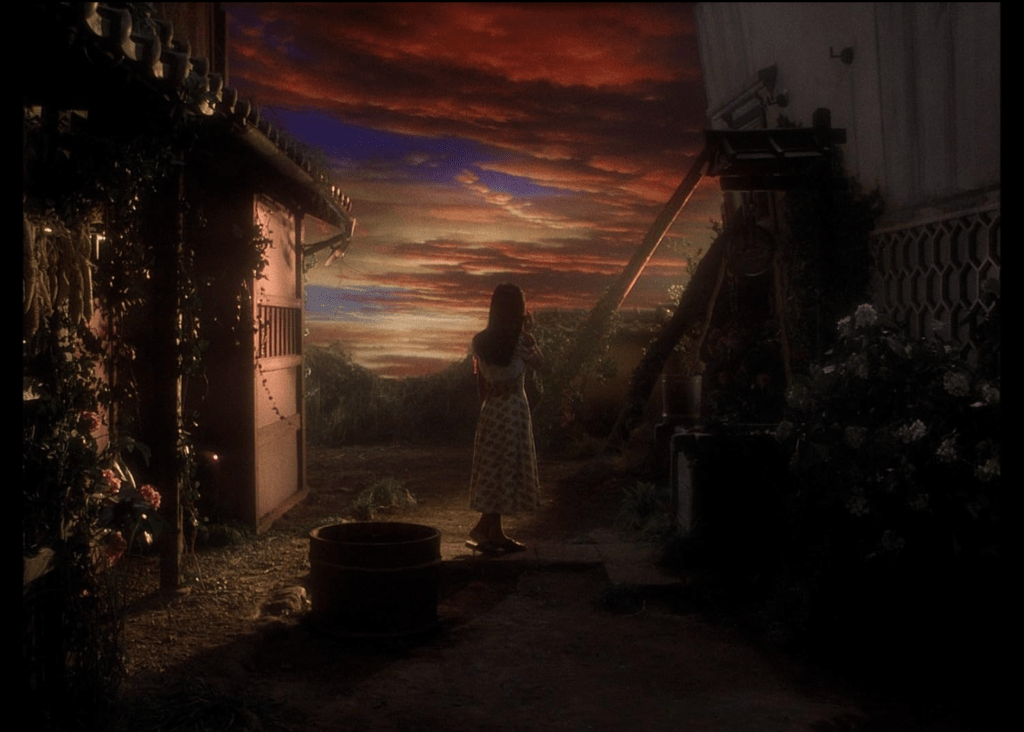

The Japanese director thought about how he should realize this cinematically and made with the talers knock, knock, knock, so the ideas bubbled out of his head: hand-painted backgrounds as if from picture books; he created with the strongest light bulbs of Japan completely overexposed moments in which the white silk sheen shone over the porcelain-like stepmother’s face ghostly and divine at the same time; cross-fades from small portrait-like image sections to large shots. Alternating as if the images were having an epileptic fit, or playful, like a child trying out the thousand and one buttons of a new toy. Then he continued with the rest of the narrative.

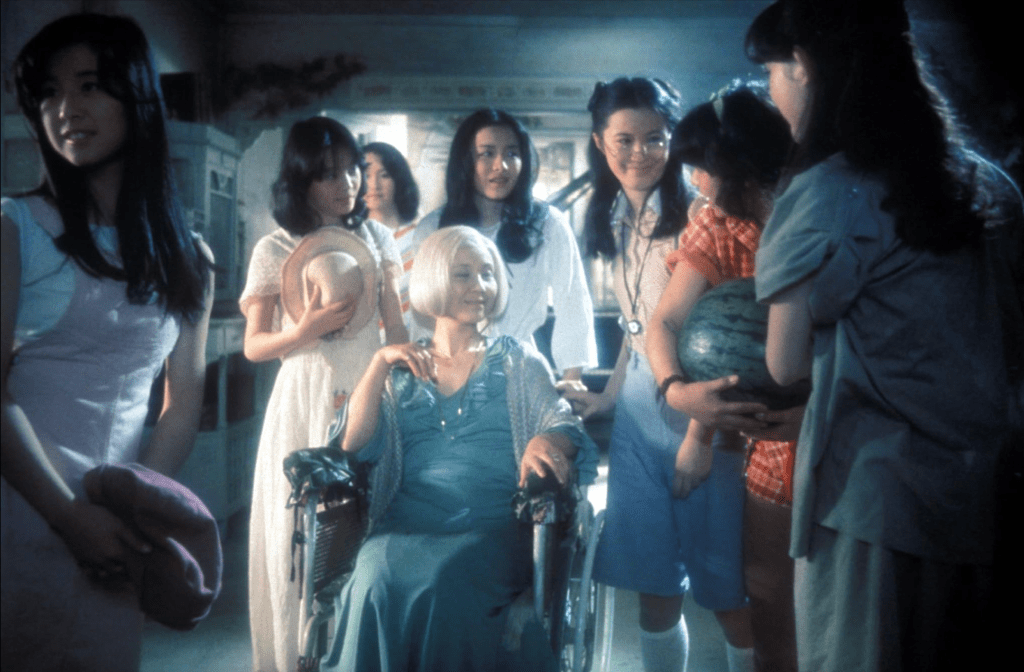

The young Gorgous decides not to go on vacation with the ole step-witch and instead to visit her aunt, the sorry sister of her deceased mother. Together with her friends Fanta the dreamy one, Kungfu the martial arts girl, Gari the analytical thinker, Sweet the loving heart friend, Melody the piano player and Mac the gluttonous all-in-one stuffer she sets off. So the seven girls set out on the rocky road to seek out their lonely, widowed aunt behind the seven mountains while playing all kinds of jokes.

The Japanese director thought about how he should realize this cinematically and made with the talers knock, knock, knock, so again the ideas bubbled out of his head. So he dedicates a performance to each of the seven girls, true to their namesake trademarks; for example, Melody, who strums melodies with her fingers over piano keys, or Mac, who can always be seen munching on buns or other food (like stomach). The journey itself is shown in an animation sequence of a train, after the girls board the train and the camera enters a boy’s picture book presenting that very train. The fate of the aunt is told to a subsequent flashback, embedded in old-fashioned, sepia-toned images and commented on by each of the girls, sometimes humorously, sometimes empathetically. Then he continued with the rest of the narrative.

With apparent kindness of heart, the aunt takes in the seven girls to her crunchy little house. But the dubious smile on her gray-haired, wrinkled face betrays that this visit means for her: seven at one stroke. The aunt’s hospitality turns into sweet and sour doom.

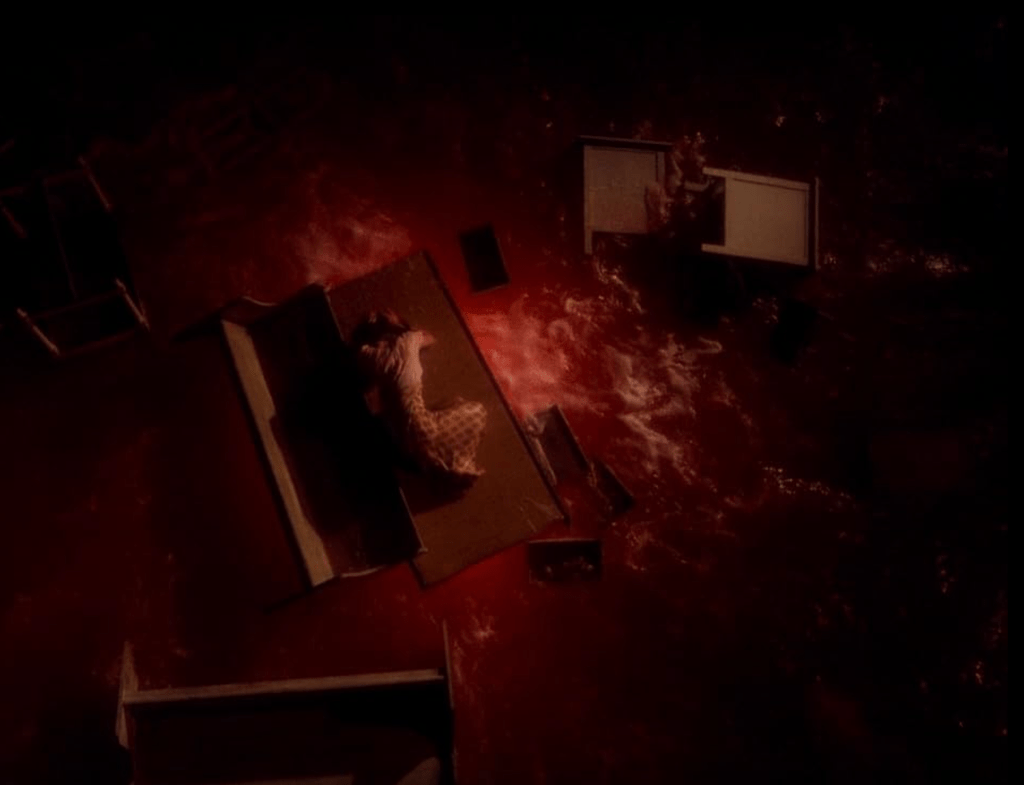

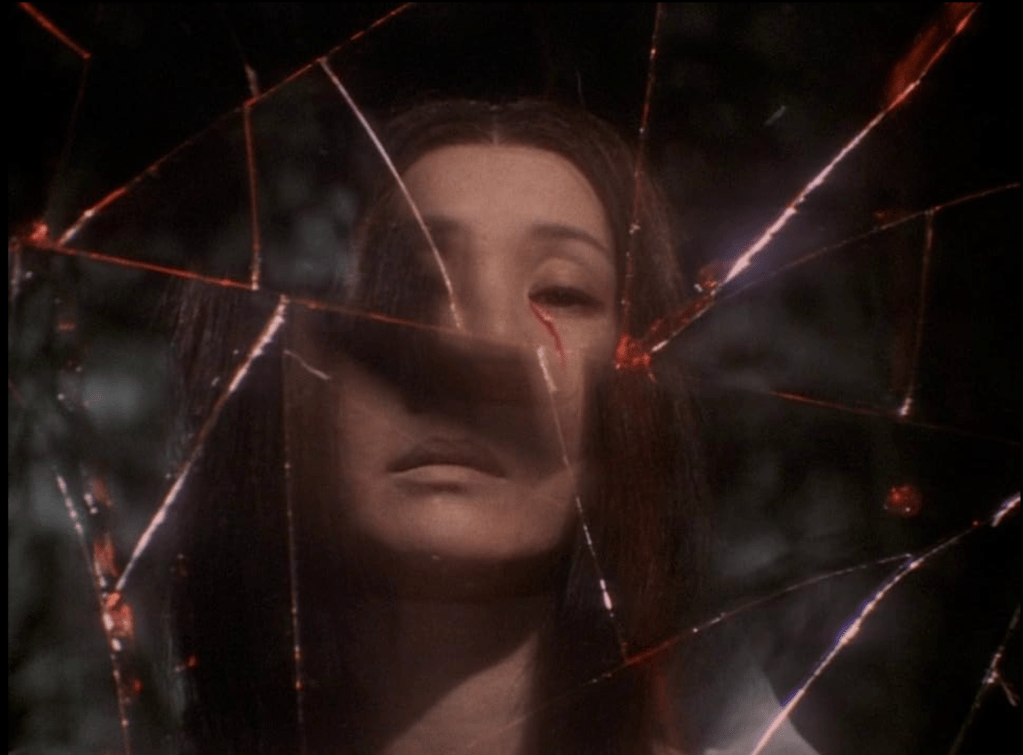

The Japanese director thought about how he should translate this into film and made knock, knock, knock with the talers, so the further ideas bubbled out of his head: A cat from which lightning shoots; eyeballs that rotate in mouths; the head of a decapitated girl floats out of a fountain and bites a friend in the rear; another like a mirror shatters into thousands of shards; another friend first has her fingertips bitten off by a piano, then her hand, and finally the piano swallows her whole; another girl is transformed into a living room chandelier. This is accompanied by the piano notes of the nursery rhyme leitmotif. Then he continued with the further narration.

Soon it becomes clear that the aunt and her crunchy witch house are for all the outlandishness. Even with the help of her otherwise only roommate, a cat that can not only open doors, but also close them. By feeding on innocence and youth, the aunt is able to rejuvenate herself to the best age of her life. But the memories of youth, first love, and her first husband, whom the war ate and spat out belching, gnaw at her soul-eatingly, so that she now feeds on souls. Gorgous, too, disappears not only into the aunt’s organic haunted house, but equally into the tragedy of the aunt herself, becoming part of this world of grief and eternal disappointment. Then also in the apparent redemption when the stepmother finally comes to visit.

The Japanese director pondered how to make this cinematic and made with the talers knock, knock, knock, so the last ideas bubbled out of his head: people transformed into bananas; in the meter-high dammed up blood pools; graphics that gyrate in cut-out techniques; the constantly scurrying around and watching grumpy pussycat; sunset shots as in an advertisement for champagne. It’s as if the director is hollowing out the film images using silhouettes and flooding in color-overloaded scenery. KAs if there were only this one film in which he could immortalize all his ideas, no matter how bizarre or crazy.

This was the story, fed by the daughter’s ideas, which enraptured the father as much as a sweet particle on a late summer autumn afternoon. Certainly it is also said that during the shoot the father pranced around the projector light and spoke, “Oh, how good it is that no one knows I shit on film rules.” At a time when Japanese traditional cinema with its traditional film rules was buried under the earth dredged up by Hollywood. So the director, with the help of his daughter, raised Japanese cinema to an incomparable ascension. Pulled upward by the winds of a frenetic and avant-garde playfulness, the knock, knock, stuffed with infantility and innocence.

And although at the box office the sack of thalers turned into a truckload of thalers, bringing the director and his daughter much good fortune and creative frolic, the critics outside the movie theaters vomited with the words: junk, junk, junk, the Japanese art with it forever away.

But even if the pithy critics have died, the cult of Hausu still lives today.

Conclusion

A bizarre fairy tale about growing up.

Facts

Original Title

Length

Director

Cast

Hausu

88 Min

Nobuhiko Ôbayashi

Kimiko Ikegami as Oshare

Miki Jinbo as Kung Fu

Kumiko Ôba as Fantasy

Ai Matsubara as Gari

Mieko Satô as Mac

Eriko Tanaka as Melody

What is Stranger’s Gaze?

The Stranger’s Gaze is a literary fever dream that is sensualized through various media — primarily cinema, which I hold in high esteem. Based on the distinctions between male and female gaze, the focus is shifted through a crack in a destroyed lens, in the hope of obtaining an unaccustomed, a strange gaze.